THE WATHELET REPORT:

Sport Governance and EU

Legal Order

WADA

Doping

FIFA Dispute Resolution

Chamber

Broadcasting Rights

White Paper on Sport

Match Fixing and

Corruption

2007/3-4

The International Sports Law Journal 2007/3-4

2007/3-4

1

CONTENTS

EDITORIAL 2

ARTICLES

Sport Governance and EU Legal Order: Present

and Future 3

Melchior Whatelet

Official Statement from WADA on the Vrijman

Report 13

Olivier Niggli

Interplay Between Doping Sanctions Imposed

by a Criminal Court and by a Sport

Organization 15

Lauri Tarast

Doping in Sport, the Rules on “Missed Tests”,

“Non-Analytical Finding” Cases and the Legal

Implications 19

Gregory Ioannidis

Termination of International Employment

Agreements and the “Just Cause” Concept in

the Case Law of the FIFA Dispute Resolution

Chamber 28

Janwillem Soek

For Whom the Bell Tolls: Sports or Commerce?

Media Images of Sports: Ideology and Identity 46

Sermin Tekinalp

Sports Broadcasting Rights in the United

States 52

John T. Wolohan

Sports Broadcasting Rights in India 60

Vidushpat Singhania

South African Measures to Combat Match

Fixing and Corruption in Sport 68

Steve Cornelius

PAPERS

The European Commission’s White Paper on

Sport 73

Michal Krejza

Mass Searches of Sports Spectators in the

United States 76

Cathryn L. Claussen

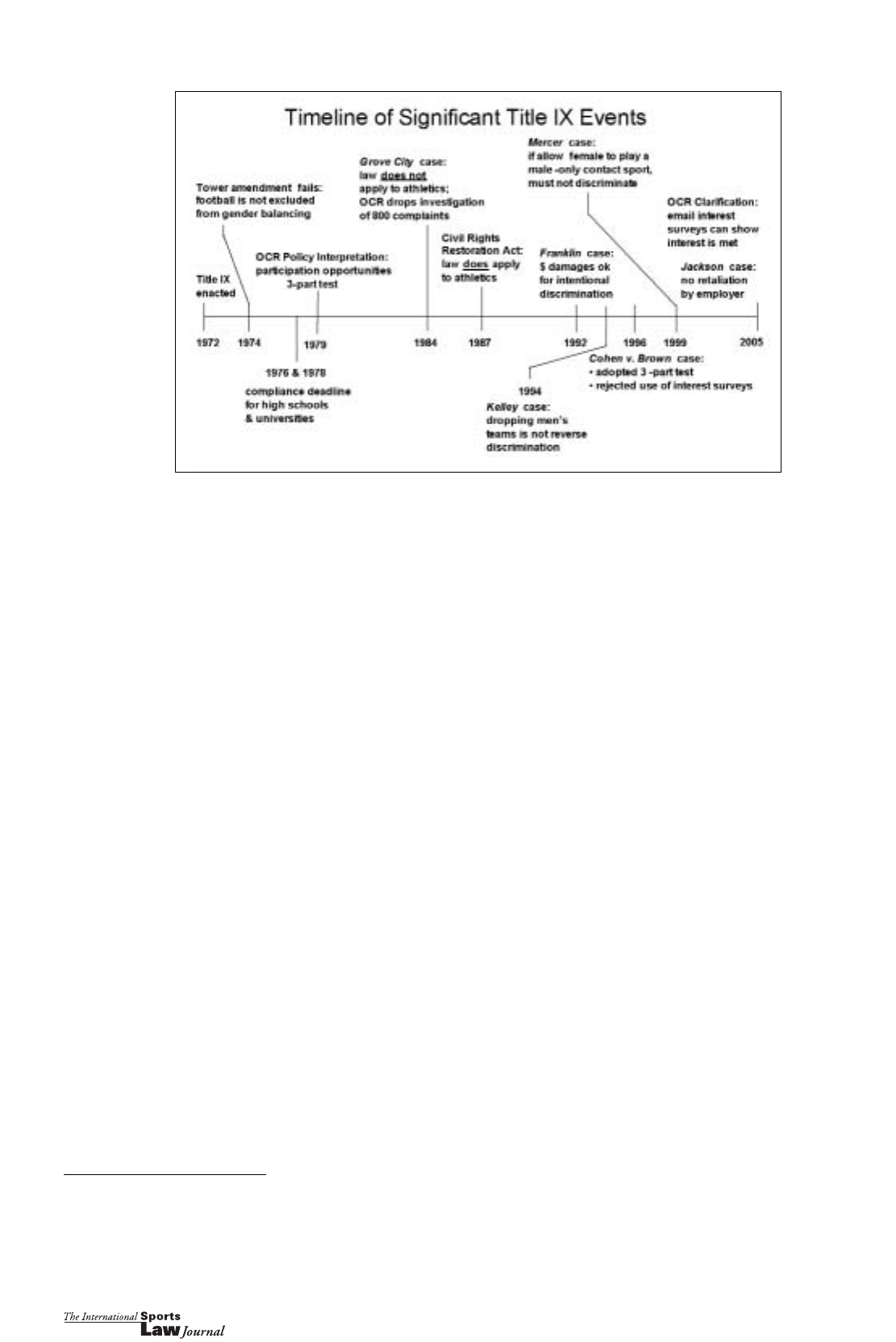

Female Sport Participation in America: The

Effectiveness of Title IX after 35 Years 79

Cathryn L. Claussen

OPINION

Manifesto: “Stop the doping inquisition!” 84

Sports Law - Worldwide Enforcement Power

Switzerland? 85

Georg Engelbrecht

The “Specificity of Sport” and the EU White

Paper on Sport: Some Comments 87

Ian Blackshaw

Formula One in New Legal Battles Off the

Track 88

Ian Blackshaw

CONFERENCES

Conclusions of the 12th IASL Conference 91 Moscow International Conference: “Sports

Law - A Review of Developments” 92

There have been several recent landmark initiatives relating to the

relationship between sport and EU law. First of all, UEFA promoted

an “Independent European Sport Review”, best known as the “Arnaut

report”, which was published in October 2006. This report strongly

supports the increased autonomy of international sports-governing

bodies from EU law. In March 2007, the European Parliament adopt-

ed a resolution on “The Future of Professional Football in Europe”,

the content of which was partly based on the Arnaut report. On 11

July 2007, the European Commission published its “White Paper on

Sport”. On 13 July 2007, UEFA issued a joint press statement togeth-

er with other European federations (ice hockey, basketball, handball,

rugby and volleyball) calling for “firmer conclusions from the

European Union to aid the future development of sport”. In particu-

lar, these federations call for “the appropriate inclusion of sport in the

reform treaty”, aimed at “fully recognising the autonomy and speci-

ficity of sport as well as the central role and independence of the

sports federations in organising, regulating and promoting their

respective sports”.

In order to contribute to the diversity of the debate, the ASSER

International Sports Law Centre has commissioned Professor

Melchior Wathelet, Universities of Louvain-la-Neuve and Liège and a

former Member of the European Court of Justice, to analyse the rela-

tionship between sport and EU law, particularly in the light of the

above-mentioned documents. Professor Melchior Wathelet was asked

to analyse the findings of the Arnaut report, de lege lata and de lege

ferenda, also taking into account the economic and political aspects

of the issues at stake.

We are very pleased that Professor Wathelet has accepted our invi-

tation and has kindly made his expert opinions available to us in this

ISLJ’s leading article on “Sport Governance and EU Legal Order:

Present and Future”. The Wathelet Report’s content is officially sup-

ported by Professor Stephen Weatherill, Jacques Delors Professor of

European Community Law, University of Oxford, United Kingdom,

Professor Roger Blanpain, Universities of Leuven (Belgium) and

Tilburg (The Netherlands), co-founder and first President of FIFPro,

Professor Klaus Vieweg, Director of the German and International

Sports Law Research Unit, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg,

Germany, Dr Richard Parrish, Director of the Centre for Sports Law

Research, Edge Hill University, United Kingdom and Dr Stefaan van

den Bogaert, Lecturer in European Law, Faculty of Law, University of

Maastricht, The Netherlands, and other academics and practitioners.

We have further received an official response from WADA on Emile

Vrijman’s leading article in ISLJ 2007/1-2 entitled “The ‘Official

Statement from WADA on the Vrijman Report’: Unintentional Proof

to the Contrary?”. We considered it our duty to make this response

which was accompanied by the Official Statement’s full text our sec-

ond leading item.

Further in this issue of ISLJ, the contribution on the White Paper on

Sport by Mr Michal Krejza, Head of the Sport Unit at the European

Commission’s Directorate-General for Education and Culture, to the

7th Asser-Clingendael International Sports Lecture in The Hague on

6 September last is published. We proudly confirm that it was the first

time after its publication that the White Paper on Sport was present-

ed at a seminar to a wider audience.

Finally, we extend a hearty welcome to Professor Paul Anderson,

Associate Director of the National Sports Law Institute at Marquette

University Law School, Milwaukee, United States of America, to

Professor Wang Xiaoping, Managing Deputy Director of the Research

Center for Sports Law, China University of Political Science and Law

(CUPL), to Dr Huang Shixi, Director of the Sports Law Center,

Shandong University, China, to Professor Denis Rogachev, Member

of the State Academy of Law, Moscow, Russia, and to Mr Gary Rice,

Partner at Beauchamps Solicitors, Dublin, Ireland, as new members

of ISLJ’s Advisory Board.

The Editors

2

2007/3-4

BOOK REVIEW

European Sports Law - Collected Papers by

Stephen Weatherill 93

HISTORY

A Law unto Himself. The Lawyer Who Changed

the Face of Football 94

EDITORIAL

❖

DOCUMENTS

White Paper on Sport 99

Independent European Sport Review 106

European Parliament Resolution on the Future

of Professional Football in Europe 113

Council of Europe Enlarged Partial Agreement

on Sport 117

UNESCO International Convention against

Doping in Sport 119

Council of Europe Anti-Doping Convention 125

World Anti-Doping Code 128

2007/3-4

3

On the future relationship between governance in European sport and

in particular professional football and the European Union legal order

Although sport is part of a healthy lifestyle and is a means of fans

devoting themselves to the game and to competition, it has also

become a professional business and an economic sector in its own

right. To a greater or lesser extent, depending on the discipline, play-

er transfers, infrastructures, media rights, advertising and sponsorship

of major national or international events now run into billions of

euros or dollars.

At a time when a new European treaty is being drafted, when new

questions are being referred to the European Court of Justice (ECJ)

for preliminary ruling when there are conflicts between players and

their clubs or clubs and their national or European federation, after

the publication on 11 July 2007 of the EU Commission’s “White

Paper on Sport”

1

, we felt it opportune to focus, both in terms of ‘lege

lata’ and ‘lege ferenda’, on European law applicable to professional

sport and, more especially, football. We will do so by taking as a start-

ing point the so-called Arnaut report, named after its author José Luis

Arnaut, former deputy prime minister of Portugal and minister of

sport in charge of Euro 2004, entitled the “Independent European

Sport Review” (IESR)

2

published in October 2006 as well as the

European Parliament resolution on the future of professional football

in Europe

3

adopted in March 2007, for commenting on the findings

and proposals contained therein as well as, in turn, offering some

thoughts and suggestions for the future of relations between the gov-

ernance of European sport and, more especially, that of football, on

the one hand, and the Community legal system, on the other.

I. Introduction

To date, sport has been organised exclusively by Member States which

regulate (often in a specific and rigorous manner) - by means of

appropriate legislation - the activities of the various stakeholders in

the sporting arena (federations, clubs, players, etc.).

And so, by way of example:

- each Member State applies its national competition law to the cen-

tralised sale, by a federation or a league, or the individual sale, of

media rights to sporting events;

- each Member State applies its Labour law to the contracts conclud-

ed between professional players and sports employers (football

clubs, basketball clubs, volleyball clubs, cycling teams etc.);

- in each Member State, it is usual for ordinary courts to decide - on

the basis of national law - on conflicts which may arise between the

various stakeholders in the sporting arena. This has resulted in a

thriving and consolidated jurisprudence.

No claims have ever been made with regard to the fact that this appli-

cation of national law to the sports sector was going against the

“autonomy required” by the federations in order to perform their

duties or that this application could be a source of “legal uncertain-

ty”. As with all other sectors of society, the sports sector and its pro-

tagonists conform - at national level - to the constraints of the rule of

law.

The European Union has no explicit competence conferred on it

when it comes to sport.

Consequently, it only intervenes in this sector by means of the

implementation of other powers invested in it, particularly with

regard to free competition and free movement for persons, services

and capital.

By means of numerous judgments and decisions, the ECJ and the

European Commission have gradually developed a jurisprudence:

- which ensures that the various stakeholders in the sports sector,

including international federations, respect fundamental freedoms

of movement and competition law;

- which, as for all other sectors, including self-employed profession-

als, rejects the concept of routine exemption for sports federations

but, on the other hand, takes into consideration the specificity of

the sport (such as its social role, the need for a certain sporting

equilibrium between the participants in a given competition, the

need to support training, etc.);

- which, consequently, decides on a case by case basis - in view of all

the circumstances of the case in point - on the question of whether

restrictions of fundamental freedoms or of free competition creat-

ed by a rule issued by a federation or by the conduct of a club or a

federation are justified by an objective of general interest and are

proportionate to the pursuit of this objective. A summary of this

jurisprudence can be found in the recent MECA-MEDINA and

MAJCEN judgment of 17 July 2006 which we will discuss later.

In short, the EU is limited to having marginal control (namely respect

for free competition and fundamental freedoms) over any abuse of

power by sports sector stakeholders, including national and interna-

tional federations.

International federations (mainly UEFA and FIFA) and to a lesser

extent the IOC, disputing European jurisprudence, believe that this

case by case approach by the ECJ and the Commission generates an

intolerable level of “legal uncertainty and confusion” and that in order

to remedy the situation it would be necessary to exempt sport from

the application of Community law (by virtue of its claimed specifici-

ty) and to reaffirm the regulatory autonomy of the federations (par-

ticularly international federations) over Community law.

This approach is clearly recommended by the so-called “ARNAUT

report” which we must stress, although entitled “independent”, is also

clearly marked “commissioned” by UEFA

4

. This is no surprise since,

although it wishes to focus on sport in general, it mainly concentrates

on the world of football.

* This report was distributed also in its

original French version throughout

Europe by means of a press-release; see

also www.sportslaw.nl/NEWS

** Universities of Louvain-la-Neuve and

Liège (Belgium) and a former Member

of the European Court of Justice. The

content of this Report is supported by

Professor Stephen Weatherill, Jacques

Delors Professor of European

Community Law, University of Oxford,

United Kingdom, Professor Roger

Blanpain, Universities of Leuven

(Belgium) and Tilburg (The

Netherlands), co-founder and first

President of FIFPro, Professor Klaus

Vieweg, Director of the German and

International Sports Law Research Unit,

University of Erlangen-Nuremberg,

Germany, and Dr Richard Parrish,

Director of the Centre for Sports Law

Research, Edge Hill University, United

Kingdom.

1 Available at this address:

http://ec.europa.eu/sport/whitepaper/

wp_on_sport_en.pdf

2 Available at this address:

www.independentfootballreview.com/

doc/Full_Report_EN.pdf (only in

English).

3 Available at this address:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/

getDoc.do?pubRef=-

//EP//TEXT+TA+P6-TA-2007-

0100+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN

4 In its 2006 annual report, the

“Independent Football Commission”,

created in 2001 at the behest of the

British government and various British

football stakeholders, with a view to

monitoring the world of football, also

examines this idea of “independence”:

“Arnaut promotes the desire for UEFA to

control all national leagues and FA’s. It

would be interesting to discover how

much input and influence UEFA had

over the compilation of the Arnaut

report” (p. 18). In its White Paper on

Sport, the European Commission indi-

cates that the Arnaut report was

financed by UEFA (Commission Staff

Working Document - The EU and

Sport: Background and Context; page 7).

Sport Governance and EU Legal

Order: Present and Future*

by Melchior Wathelet**

ARTICLES

II. The state of Community law

As stated, we will try to describe the state of Community law by start-

ing from the approaches that we feel are being upheld by the Arnaut

report.

A. What would be the rules adopted by the sporting federations

which, on the basis of European Court of Justice jurisprudence,

are beyond the scope of Community law?

Rules which, according to the Arnaut report, would certainly be

beyond the scope of Community law and would, therefore, be up to

the “sole discretion of the sports governing bodies” would, in partic-

ular, include the rules of the game, rules relating to the structure of

competitions, rules making it possible for federations to establish

sporting calendars, the “home and away” rule, rules relating to the

fight against doping and finally, rules relating to the obligation placed

on clubs to make their employees available, free of charge, to nation-

al teams, this rule being “motivated by purely sporting considera-

tions” and having, therefore, to be “considered as a prime example of

a ‘sporting rule’ which should fall outside the scope of EU law”

5

.

The authors of the report could have been able to base their find-

ings on a phrase from an already outdated judgment by the Court of

Justice, known as the WALRAVE

6

judgment where, for the first time,

the Court had applied rules relating to free movement of workers to

the field of sport and had stated that sport was only subject to

Community law when it constituted an economic activity in the sense

of article 2 of the EC Treaty, tempering this approach to rules of pure-

ly sporting aspects and (which) as such (have) nothing to do with eco-

nomic activity (paragraph 4).

Subsequent jurisprudence ought to have already convinced the

authors of the Arnaut report of the non-existence of the principle of

widespread exemption for “purely sporting rules”. In fact, both in the

BOSMAN judgment of 1995 (which decided that the system of fee

paying transfers at the end of an employment contract was contrary

to Community law and, likewise, the quota rule, fixing the maximum

number of players from other Member States able to take part in a

match between clubs) (paragraph 76) and in the DELIEGE judgment

of 2000 (the only case in jurisprudence where the Court recognised

the purely sporting nature of a rule in respect of a regulation not

involving the composition of national sports teams but relating to the

selection of athletes for high-level international competitions) (para-

graph 43), the Court had already specified that any restriction of the

scope of Community provisions “must remain limited to its proper

objective” and henceforth, cannot “be relied upon to exclude the

whole of a sporting activity” from the scope of the Treaty

7

.

Even on this now outmoded basis, it certainly does not appear rea-

sonable to believe that arranging sporting calendars, which in fact

consists of distributing all the production capabilities of the “football

product” between clubs and federations, or the obligation to make

players available, which makes it possible, for example, for FIFA to

organise a World Cup with a commercial value running into billions

of Euro (this event being, by its very nature, in direct competition

with products offered by the clubs) should, a priori, escape investiga-

tion by Community judges.

It is, however, above all, highly surprising that no major reference

is made in the Arnaut report to the MECA-MEDINA and MAJCEN

judgment, even though this was given prior to publication of the

report in question and which, in relation to anti-doping rules, very

clearly moved the boundary between sporting regulations which

escape the application of Community law and those falling within its

scope

8

. The moment that any sporting rule has an economic effect,

even if this is an ancillary economic effect, it will fall within the scope

of the major freedoms of movement and competition law. The Court,

in effect, states that “the mere fact that a rule is purely sporting in

nature does not have the effect of removing from the scope of the

Tr eaty the person engaging in the activity governed by that rule of the

body which has laid it down” (paragraph 27) and that “if the sporting

activity in question falls within the scope of the Treaty, the conditions

for engaging in it are then subject to all the obligations which result

from the various provisions of the Treaty” (paragraph 28)

9

.

Let us remember that, in this case the Court quashed a judgment

of the Court of first instance which, basing its judgment on the prem-

ise that “the prohibition of doping is based on purely sporting consid-

erations and therefore has nothing to do with any economic consid-

eration” (paragraph 47) had concluded that anti-doping rules, and

more particularly, the disputed anti-doping regulation, did not fall

within the scope of treaty provisions on economic freedoms and free

competition, did not pursue any discriminatory purpose and, there-

fore, constituted a purely sporting rule, even though it did have eco-

nomic repercussions (paragraph 49 and paragraph 52). In contrast, the

Court of Justice applies the so-called Wouters jurisprudence

10

to anti-

doping regulations, mindful of the fact that compatibility of a regula-

tion with Community law cannot be applied in an abstract manner,

that it is necessary to take into consideration the global context in

which the rule has been enacted or in which it deploys its effects prior

to investigating whether or not the resulting restrictive effects on

competition are inherent to the pursuit of the legitimate objectives

sought by it and are in proportion to said objectives.

Let us remember that the fact that a regulation falls within the

scope of Community law does not mean that it is necessarily incom-

patible with said law. The Court did, in fact, state in the same judg-

ment that an anti-doping regulation does not “necessarily constitute a

restriction of competition incompatible with the common market,

within the meaning of Article 81 EC Treaty, since they are justified by

a legitimate objective. Such a limitation is inherent in the organisa-

tion and proper conduct of competitive sport and its very purpose is

to ensure healthy rivalry between athletes” (paragraph 45).

That said, once a legitimate objective has been defined, it is once

again necessary to determine whether the regulation is proportionate,

i.e. limited to what is required in order to achieve the objective in

question, in this case, the correct conclusion of sporting competi-

tions.

In the case in point, in the Court’s opinion, examination of the

proportionality of an anti-doping rule must relate both to the level at

which the margin of tolerance over which doping is punishable is set

and the severity of the sanctions laid down.

In this regard, let us take two other examples.

In quoting the decision given by the Belgian Competition Council

(on the licensing system put in place by the Royal Belgian Football

Association), the authors of the Arnaut report believe that rules relat-

ing to “club licensing” - intended to encourage strong governance and

financial stability and transparency within clubs - should “also fall

within the legitimate autonomy of the sports authorities” (p.45).

The Belgian Competition Council, in its decision No. 2004-E/A-

25 of 4 March 2004

11

, did not confirm “the autonomy” of the Royal

Belgian Football Association in terms of the “club licensing system”.

In effect, the Competition council judged that: “The two provisions

are necessary for the organisation of sporting events. They aim to ensure the

equilibrium of sporting events, uncertainty in respect of results and to pro-

vide the sector with sound financial management. Although they may

4

2007/3-4

ARTICLES

5 Page 42.

6 Judgment of the Court of 12 December

1974, B.N.O. Walrave and L.J.N. Koch

v. Association Union Cycliste

Internationale, Case C-36/74, European

Court reports 1974, page 1405.

7 Judgment of 15 December 1995, Bosman,

Case C-415/93, European Court reports,

page I-4921 and Judgment of 11 April

2000, Deliège, Case C-51/96, European

Court reports, page I-2549.

8 Judgment of 10 July 2006, Case C-

519/04, not yet published. This lack of

reference is even more surprising since

the judgment did not fail to draw the

attention of UEFA. In fact, UEFA’s

Director of Legal Affairs, Gianni

Infantino, talked about it as “a step

backwards for the European Sports

model and the Specificity of Sport”, as

“a strange twist” and as a judgment that

is “unsatisfactory from a legal point of

view” (article available at this address,

http://www.uefa.com/uefa/keytopics/kin

d=2048/newsid=574246.html# under the

heading “Sport specificity - UEFA analy-

sis”).

9 See in the Jurisprudence Liège Mons

Bruxelles, 2006, page 1792, “L’arrêt

MECA-MEDINA et MAJCEN: plus

qu’un coup dans l’eau”, by Melchior

Wathelet.

10 Judgment of 19 February 2002, Case C-

309/99, European Court reports, page I-

1577.

11 Competition Council, Decision No.

2004-E/A-25 of 4 March 2004, case

CONC-E/A-01/0039, published in the

“Revue trimestrielle de jurisprudence du

Conseil de la Concurrence” 2004/01,

page128.

2007/3-4

5

ARTICLES

impose constraints, the Council notes that these are inherent to the pursuit

of the legitimate objective sought and are proportionate to this objective.

In this sense, the Royal Belgian Football Association has perfectly ful-

filled its role as regulator.

Consequently, it is necessary to decide that the provisions are beyond the

scope of article 2, paragraph 1, of the law”.12

It is, therefore, in application of the “inherent” test, as formulated

by the ECJ in the WOUTERS judgment

13

and - more specifically for

sport - in its recent MECA-MEDINA and MAJCEN judgment,

mentioned above, and, therefore, on the basis of a concrete examina-

tion of the disputed provisions that the Competition Council has

concluded that there was no breach, in the case in point, of Belgian

competition law.

By basing its findings on the judgment given by the Court of

Arbitration for Sport in the ENIC case and on the positions taken by

the European Commission on this same case, the authors of the

report believe, with regard to rules aiming to prevent multi-ownership

or the influencing of clubs by third parties, that “the discretion of the

football authorities to take the necessary steps to safeguard the integrity of

the competitions that they organised should also be respected as matters

falling within their natural sphere of competence».

Once again, the authors of the Arnaut report seem to confuse com-

patibility with Community law of the UEFA rule prohibiting - to a

certain extent - multi-ownership, and non-application of Community

law.

In fact, in its decision to dismiss the complaint filed on 27 June

2002 (in the case COMP/37806: ENIC/UEFA)

14

, the Commission in

no way believed that the UEFA rule was beyond the scope of

Community law (and, so, would come under the sole “discretion” and

the UEFA’s “natural sphere of competence”).

On the contrary, by invoking the WOUTERS judgment, men-

tioned above, the Commission decided that said rule falls within the

scope of article 81 of the EC Treaty but that its restrictive effects on

competition are inherent “in the pursuit of the very existence of credible

pan European football competitions “

15

and that “the limitation of the

freedom of action of clubs and investors which the rule entails does

not go beyond what is necessary to ensure its legitimate aim: i.e. to

protect the uncertainty of the results in the interest of the public.”

16

Once again therefore, it is after a concrete examination of the rule’s

objective and its effects, within the field of application of Community

law, that a compatibility report can be drawn up, with no means of

deducing, a priori, compatibility with Community law of any rule on

multi-ownership (and even less so the non-application of this law to

such rules).

In other words, in the light of the MECA-MEDINA and MAJ-

CEN judgment, even the fact that a rule is adopted and implement-

ed by a federation or the IOC in its capacity as regulator (anti-doping

rules certainly being one example of this) and not as an economic

agent, under no circumstances results in this rule being exempted

from the scope of Community law in general and articles 81 and 82 of

the EC Treaty in particular, the moment that it has economic conse-

quences and affects one or more freedoms drawn by third parties from

the EC Treaty.

B. What criteria have to be fulfilled for rules issued by sporting

federations and falling within the scope of Community law to be

declared acceptable?

Here again, we believe the Arnaut report’s analysis to be disputable in

so far as it systematically neglects the fact that a declaration of com-

patibility with Community law is only ever made after analysis, in

each individual case, of the suitability of the rule as regards the gen-

eral interest objective sought and its proportionality.

Let us take some examples:

1. Organisation of competitions

The rules under which federations may impose total acceptance of

competitions forming part of the European pyramid on clubs would

be compatible with Community law.

And so, both at national and European level “the football authori-

ties may legitimately require their members to commit to participation in

the pyramid or co-operative structure as a whole and not merely in one or

other part of it”

17

.

To this end, the authors of the report invoke ECJ jurisprudence

under which it is lawful for a cooperative’s articles of association to

prohibit its members from participating in other organisations in

direct competition with said cooperative.

Upon reading the GØTTRUP-KLIM judgment invoked

18

, it is

hard to see how this jurisprudence could be used to prove the essen-

tial nature of the pyramidal organisation. In fact, paragraphs 32, 34

and 35 of this judgment lay down that:

32. In a market where product prices vary according to the volume of

orders, the activities of cooperative purchasing associations may,

depending on the size of their membership, constitute a significant

counterweight to the contractual power of large producers and make

way for more effective competition.

34. It follows that such dual membership would jeopardize both the

proper functioning of the cooperative and its contractual power in rela-

tion to producers. Prohibition of dual membership does not, therefore,

necessarily constitute a restriction of competition within the meaning

of Article () of the Treaty and may even have beneficial effects on

competition.

35. Nevertheless, a provision in the statutes of a cooperative purchasing

association, restricting the opportunity for members to join other types

of competing cooperatives and thus discouraging them from obtaining

supplies elsewhere, may have adverse effects on competition. So, in order

to escape the prohibition laid down in Article () of the Treaty, the

restrictions imposed on members by the statutes of cooperative purchas-

ing associations must be limited to what is necessary to ensure that the

cooperative functions properly and maintains its contractual power in

relation to producers.

We have, therefore, noted that the ECJ did not authorise, in abstrac-

to, the prohibition of dual membership but that upon completion of

a concrete examination of the objective sought and the necessity of

the means employed, decided - in the case in point - that this type of

ban does not breach Community competition law.

In addition, in the GØTTRUP-KLIM case, the ban on dual mem-

bership aimed to make it possible to place a “counterweight to the con-

tractual power of large producers” and make way for “more effective com-

petition”. In professional sport, a ban on existing, in part, outside the

pyramid would appear both in its aims and effects to prevent the

appearance of competing producers. Here we have two very different

situations.

In any event, it is clear that it would be wrong to try to prevent (a

priori and on the grounds of the allegedly lawful nature of the pyram-

idal organisation) the players or clubs involved from raising the ques-

tion, by means of appropriate recourse, of the legality under

Community law of certain rules involved in the construction of the

pyramidal model.

. Player transfers

The same reasoning can be applied to rules on player transfers.

In fact, in both the BOSMAN

19

and the LEHTONEN

20

judgments,

the ECJ judged that the transfer rules would restrict the free move-

12 Unofficial translation from the French

original.

13 See above.

14 Available in English at the following

address: http://ec.europa.eu/comm/com-

petition/antitrust/cases/deci-

sions/37806/en.pdf

15 Points 31 and 32 of the decision.

16 EC Press release of 27 June 2002, ref .

IP/02/942.

17 Arnaut report, page 36.

18 Judgment of 15 December 1994, Case C-

250/92, European Court reports. page. I-

5641.

19 ECJ, 15 December 1995, Bosman, Case

C-415/93, European Court reports, page

I-4921, pts 99, 100 and 120.

20 ECJ, 13 April 2000, Lehtonen, Case C-

176/96, European Court reports, page I-

2681, pts 49 and 50.

ment of players and would, therefore, constitute an obstacle on this

fundamental right invested by the EC Treaty. It was only in the sec-

ond instance that the Court verified “whether that obstacle may be

objectively justified”21, which may be the case - for example - if the

deadlines set for player transfers were required in order to ensure “the

regularity of sporting competitions”

22

.

Both in the BOSMAN and the LEHTONEN judgments, the

Court judged that the regulations in question went “beyond what is

necessary for achieving the aim pursued”.

It is, therefore, really by means of a case by case, rather than a gen-

eral examination, that certain rules relating to a transfer system may

possibly be declared to conform to Community law. A fortiori, it is

out of the question that some of these rules fall beyond the scope of

Community law, as is, however, maintained by the Arnaut report.

23

. The activity of players’ agents

Claiming a greater role for UEFA in this respect (at the present time

essentially managed by FIFA), the Arnaut report believes that these

rules are inherent “to the proper regulation of sport and therefore com-

patible with European Community law”24.

In referring to inherence criteria, the authors of the Arnaut report

fall neatly within the framework traced by WOUTERS and MECA

jurisprudence.

It cannot, however, be claimed, as they seem to do, that all rules

relating to the activity of players’ agents are inherent to the smooth

operation of the football market and, therefore, compatible with

Community law.

Once again, the Community judge will assess whether the

restraints on the freedom of action of players’ agents that the rule cre-

ates are inherent to the achievement of the legitimate objective

sought, on a case by case basis.

Finally, in its PIAU judgment

25

, encouraged to make a decision on

the compatibility of the FIFA judgment on the activity of players’

agents with articles 81 and 82 of the EC Treaty, the Court of first

instance judged that: “On the one hand, the Players’ Agents Regulations

were adopted by FIFA of its own authority and not on the basis of rule-

making powers conferred on it by public authorities in connection with a

recognised task in the general interest concerning sporting activity (see, by

analogy, Case C-309/99 Wouters and others [2002] ECR I-1577, para-

graphs 68 and 69). Those regulations do not fall within the scope of

the freedom of internal organisation enjoyed by sports associations

either (Bosman, paragraph 81, and Deliège, paragraph 47).

On the other hand, since they are binding on national associations that

are members of FIFA, which are required to draw up similar rules that

are subsequently approved by FIFA, and on clubs, players and players’

agents, those regulations are the reflection of FIFA’s resolve to coordinate

the conduct of its members with regard to the activity of players’ agents.

They therefore constitute a decision by an association of undertakings

within the meaning article 81 (1) EC (Case 45/85 Verband der

Sachversicherer v Commission [1987] ECR 405, paragraphs 29 to 32,

and Wouters and others, paragraph 71), which must comply with the

Community rules on competition, where such a decision has effects

in the Community.

With regard to FIFA’s legitimacy, contested by the applicant, to enact

such rules, which do not have a sport-related object, but regulate an eco-

nomic activity that is peripheral to the sporting activity in question and

touch on fundamental freedoms, the rule-making power claimed by a pri-

vate organisation like FIFA, whose main statutory purpose is to promote

football (see paragraph 2 above), is indeed open to question, in the light

of the principles common to the Member States on which the

European Union is founded.

The very principle of regulation of an economic activity concerning

neither the specific nature of sport nor the freedom of internal organisa-

tion of sports associations by a private-law body, like FIFA, which has not

been delegated any such power by a public authority, cannot from the out-

set be regarded as compatible with Community law, in particular with

regard to respect for civil and economic liberties.

In principle, such regulation, which constitutes policing of an econom-

ic activity and touches on fundamental freedoms, falls within the compe-

tence of the public authorities. Nevertheless, in the present dispute, the

rule-making power exercised by FIFA, in the almost complete absence of

national rules, can be examined only in so far as it affects the rules on

competition, in the light of which the lawfulness of the contested decision

must be assessed, while considerations relating to the legal basis that allows

FIFA to carry on regulatory activity, however important they may be, are

not the subject of judicial review in this case.”

These are the most relevant Court findings and they continue to be

topical.

. UEFA rules on “homegrown players”

Here again, the Arnaut report believes that the rules requiring each

club to have a certain number of players under contract who have

been trained either at the club or within the national federation to

which this club belongs

26

are necessarily compatible with Community

law.

Again, it would seem risky to uphold this principle, even acknowl-

edging that, to a certain extent, these rules may be justified by an

objective of general interest and are proportionate

27

.

In paragraph 106 of the BOSMAN judgment, the ECJ judged that:

“In view of the considerable social importance of sporting activities, and

in particular football in the Community, the aims of maintaining a bal-

ance between clubs by preserving a certain degree of equality and uncer-

tainty as to results, and of encouraging the recruitment and training of

young players must be accepted as legitimate” (our underlining).

UEFA invokes these two justifications but also maintains that this

system provides “a large reservoir of talent for national teams as a con-

sequence”.

Likewise, UEFA acknowledges that its rule favours the recruitment

of “homegrown” nationals rather than nationals from other Member

States, thereby creating an indirectly discriminatory obstacle.

Furthermore, it is doubtful that this rule contributes to competi-

tive equilibrium on a transnational level. In effect, nothing will pre-

vent - in a given Member State - the richest club from acquiring the

best “homegrown players” prior to training. This was, in addition,

explicitly judged by the ECJ in point 135 of the BOSMAN judgment,

in respect of nationality clauses (the “homegrown players” clause, as

only constituting, in our opinion, a positivised and “restyled” version

of the nationality clause) ; “although it has been argued that the nation-

ality clauses prevent the richest clubs from engaging the best foreign play-

ers, those clauses are not sufficient to achieve the aim of maintaining a

competitive balance since there are no rules limiting the possibility for

such clubs to recruit the best national players, thus undermining that bal-

ance to just the same extent”.

What is more, this rule will penalise clubs in small Member States,

which will be disadvantaged by the narrowness of their national

labour market.

. The centralised marketing of media rights

Here again, the authors of the Arnaut report believe that the concept

of the sale or individual ownership of television rights cannot be

accepted from an intellectual point of view.

Referring to the findings of Mr Advocate General LENZ in the

BOSMAN case (“certain restrictions may be necessary to ensure the prop-

6

2007/3-4

ARTICLES

21 ECJ, 13 April 2000, Lehtonen, Case C-

176/96, European Court reports, page I-

2681, pt 51.

22 ECJ, 13 April 2000, Lehtonen, Case C-

176/96, European Court reports, page I-

2681, pt 53.

23 Arnaut report, page 105

24 Arnaut report, p.47.

25 Judgment of the Court of first instance

judgment of 26 January 2005, Case T-

193/02, European Court reports, page.

II-209 (paragraphs 74 to 78).

26 Arnaut report, p. 49 and 50.

27 On page 7 of the “White Paper on

Sport” of July 2007, to which we will

return later, the Commission does not

state otherwise. “Rules requiring that

teams include a certain quota of locally

trained players could be accepted as

being compatible with the Treaty provi-

sions on free movement of persons if

they do not lead to any direct discrimi-

nation based on nationality and if possi-

ble indirect discrimination effects result-

ing from them can be justified as being

proportionate to a legitimate objective

pursued, such as to enhance and protect

the training and development of talented

young players. The ongoing study on

the training of young sportsmen and

sportswomen in Europe will provide

valuable input for this analysis.”

2007/3-4

7

ARTICLES

er functioning of the sector”) and the decision of the European

Commission in the UEFA Champions League Media rights case, the

authors of the report conclude that “It is both acceptable and necessary

for the football authorities to require clubs to commit to a central market-

ing model as a condition of their participation in a sporting competition

and compatible with European law”

28

.

Firstly, when we are talking about media rights, we must avoid any

confusion between the question of ownership of rights, entitlement to

said rights, and their mode of marketing.

Contrary to what is maintained by the authors of the Arnaut

report, the principle of individual ownership of these media rights is

not only intellectually conceivable but is part of substantive law.

There is no unified or harmonised system of ownership within the

European Union, the organisation of these systems coming under the

jurisdiction of each Member State. The question of a property own-

ership system (and, therefore, in particular, that of knowing if said

right belongs individually to a club or is jointly owned by several

clubs) is governed by national law in each Member State. This was

noted by the European Commission in its decision of 23 July 2003

relating to the joint selling of the commercial rights of the UEFA

Champions League

29

. In a certain number of Member States, the

individual ownership formula was upheld

30

.

It should then be analysed whether the joint sale of these rights,

grouped together by an agreement between the individual owners or

the co-owners, is compatible with article 81 (1) of the EC Treaty, as the

Commission states in paragraphs 122 to 124 of its decision as referred

to above:

122. (...) on the basis of the information submitted by UEFA,

UEFA can at best be considered as a co-owner of the rights, but never

the sole owner. The question of ownership is for national law and the

Commission’s appreciation of the issue in this case is without prejudice

to any determination by national courts.

. The Commission therefore proceeds on the basis that there is co-

ownership between the football clubs and UEFA for the individual

matches, but that the co-ownership does not concern horizontally all

the rights arising from a football tournament. It is not considered nec-

essary for the purpose of this case to quantify the respective ownership

shares.

. It suffices to note that there are multiple owners of the media

rights to the UEFA Champions League. An agreement between the

three owners (the two football clubs and UEFA) which are indispensa-

ble to produce one unit of output (the license to broadcast one match)

would not be caught by Article () of the Treaty and Article () of

the EEA Agreement. However, since the agreement regarding UEFA’s

joint selling arrangement extends beyond that, Article () of the

Treaty and Article () of the EEA Agreement apply to the arrange-

ment.

After a detailed investigation, the Commission considered that this

joint sales agreement would generate restraints on competition in the

sense of article 81 (1) of the EC Treaty but could, to a certain extent,

benefit from the exemption provided for in 81 (3) of the EC Treaty, by

virtue of improvements in production and distribution brought about

by these restraints and by virtue of the fact that an adequate share of

the resulting profits would return to consumers.

The Commission decided, however, that: “Exemption should (...) be

subject to the condition that football clubs must not be prevented from

selling their live TV rights to free-TV broadcasters where there is no rea-

sonable offer from any pay-TV broadcaster”.

In conclusion, once again, it was after concrete analysis that, to a

certain extent, some joint sales agreements were declared to conform

to Community law.

Furthermore, it should be noted that the Commission based its analy-

sis on the premise that this joint sale resulted from the free consent of

the clubs involved. It is, therefore, wrong for the Arnaut report to

deduce from this decision that it would permit federations to impose

a “central marketing model” on clubs as a condition of their partici-

pation in a sporting competition.

It is, on the contrary, the free consent of the clubs involved which

makes it possible for this model to be conceived and, to a certain

extent, to benefit from the exemption laid down by article 81 (3) of

the EC Treaty.

III. The specificity of sport

Apart from the fact that they have never been taken into considera-

tion or accepted by the Court of Justice, certain arguments presented

in the Arnaut report attempt to demonstrate that sport should merit

different treatment from that reserved for other sectors of economic

life.

We admit that on the basis of this type of reasoning, numerous sec-

tors of socio-economic activity could claim a right to exemption from

the application of Community law on the grounds of their exception-

ality. Do the aeronautics, forestry, health, energy, waste and telecom-

munications industries not have their own specificity? In any event,

both Court of Justice and Commission jurisprudence upholds, by

way of justification of restraints on fundamental freedoms or on free

competition, objectives of legitimate interest which may differ

according to sector and the sports sector has, furthermore, benefited

from this.

Blanket exemption from Community law of sporting regulations

cannot, of course, be justified, as in the Arnaut report, due to the need

to give the relevant bodies a guarantee of being able to act “without

fear of their decisions being undermined by the application of

European Community law” (page 31 of the Arnaut report). Legal dis-

putes are created and legal decisions are given in all sectors of social and

economic life. There is no more legal uncertainty in the field of sport

than in other sectors, both with regard to fundamental freedoms and

competition regulations and only legislation and jurisprudence can

reduce this uncertainty which also results from the changing behaviour

of the stakeholders in a given sector. In any event, the solution to legal

uncertainty is never to adopt “soft law” or to leave the law to private

stakeholders, even if UEFA and the national federations could be con-

sidered to be pure regulators, which they are not. They are also leading

economic agents in a market that they are also called upon to regulate.

With very few exceptions, they are called upon to adopt regulations

and decisions of a mixed nature which contribute both to the regula-

tion of the professional football market and to the promotion of their

own economic and commercial interests. And so, when UEFA fixes

the dates of the final phase of the European Championship which is

held in June, it reserves this period of production for itself and makes

it unavailable for clubs, with the positive or negative economic conse-

quences that this may bring for either party.

There is, therefore, no reason why, in the name of the specificity of

the sports sector, sports federations should be exempted from the

application of a law which is applied, for example, to certain associa-

tions of professionals, as in the WOUTERS judgment, which relates

to a national Bar Association.

The Arnaut report also refers, at great length, to the “European

sporting model”, the principles of which would be respected, in full,

by UEFA. This model would be based on democratic operation, the

separation of powers, the representation of the various stakeholders

(players, supporters, clubs, federations) within consultative bodies,

the principle of promotion/relegation (with the resultant pyramidal

structure), financial solidarity guaranteeing a certain degree of equi-

librium in respect of the sporting powers-that-be and recourse to arbi-

tration.

Prior to commenting on some of these points, even if we suppose

that these points have all been made, we do not see why said points

would justify the exemption of sport from Community law, and more

specifically, from provisions relating to the freedom of movement and

competition.

28 Arnaut report, p. 52.

29 COMP/C.2-37.398, Official Journal of

the European Union L291/25, 8.11.2003.

30 See points 121 and subsequent points of

the decision and, in particular, footnote

59.

Although the impression given by sports federations is sometimes that

of public authorities, they are still no more than private entities

involved in economic and commercial activities and are, moreover,

generally constituted under Swiss law.

In the aforementioned PIAU judgment, the Court of First Instance

demonstrated the purely private nature of an international federation,

acting “on its own authority and not on the basis of rule-making powers

conferred on it by public authorities in connection with a recognised task

in the general interest concerning sporting activity...”. Even though a Bar

Association receives this type of mission from the national legislator,

its decisions are still subject to competition law

31

. Even more so for

sports federations.

Consequently, it would seem to be inappropriate to compare the

division of tasks put in place within UEFA, a purely private entity,

with a separation of powers, as practised by democratic States gov-

erned by the rule of law and falling within public law.

In addition, it is public knowledge that some clubs, particularly

those in the G-14 group

32

, do not share the analysis made by the

authors of the Arnaut report, that clubs within UEFA are fully satis-

fied, particularly with regard to democratic requirements and mecha-

nisms of “representation” .

In this respect, the authors of the Arnaut report believe that a pure-

ly consultative representation is sufficient. In our opinion, this is not

the case since the degree of participation of clubs in decision making

has necessarily to vary according to the issues in question.

And so, simply by way of example, the proven status of the clubs

participating in the UEFA Champions League as co-owners, necessar-

ily requires co-management of the commercial rights on which this

co-ownership is based. In effect, in view of general legal principles on

the subject of managing ‘res communis’, UEFA’s claim for exemption

from said management for all the other co-owners is not reasonably

justifiable and, consequently, abusive

33

.

Even if the principle of promotion/relegation, which means that

the clubs at the top of the sporting pyramid never have a legal guar-

antee that this situation will continue, can be accepted, there can be

no question of requiring clubs to waive any right of criticism of these

procedures, if necessary, by legal means, whether these criticisms

relate to the format of the different competitions or the sporting cal-

endar and of requiring application of the principle of proportionality

to be monitored.

Although financial solidarity and revenue sharing are certainly one

means of serving an objective deemed worthy of protection, i.e.

maintaining a degree of equilibrium of the sporting powers-that-be,

there is no question that any income sharing would necessarily be

acceptable under Community law. It suffices to remember that in

paragraph 228 of the opinion in the BOSMAN case, Mr Advocate

General LENZ prudently expressed himself as follows: “Mr

BOSMAN submitted a number of economic studies which show that dis-

tribution of income represents a suitable means of promoting the desired

balance. The concrete form given to such a system will of course depend

on the circumstances of the league in question and on other considera-

tions. In particular it is surely clear that such a redistribution can be sen-

sible and appropriate only if it is restricted to a fairly small part of

income: if half the receipts, for instance, or even more was distributed to

other clubs, the incentive for the club in question to perform well would

probably be reduced too much”.

In addition, there is a certain degree of contradiction, indeed

incompatibility, between the principles of “promotion/relegation” and

“competitive balance” (used for revenue sharing).

In effect, revenue sharing is a concept deriving from American pro-

fessional sports, which are characterised by closed leagues (NBA,

NFL, etc.). In the United States, although revenue sharing exists, it is

only between members of the same elite, guaranteed not to be relegat-

ed to a lower category.

In other words, it is the absence of “promotion/relegation” which

makes the widespread practice of “revenue sharing” acceptable.

Furthermore, the reticence of the major clubs in each league to

support revenue sharing is accentuated by their desire to be competi-

tive in Europe.

Finally, if arbitration is an acceptable method of conflict resolution,

it is not acceptable for the various stakeholders within professional

sport to have to waive the right to take action through the ordinary

courts, in particular, in order to contest the legality of certain federa-

tion decisions in respect of Community law.

This obligation to permit the ‘ordinary man in the eyes of the law’

to appear before ordinary courts was one of the conditions imposed

by the European Commission on FIFA to put an end to the infringe-

ment proceedings relating to transfer rules that it had instituted

against FIFA

34

.

The lack of restrictive and exclusive recourse to arbitration does not

in any way harm its efficacy, as illustrated by the FIFA Regulations

“for the Status and Transfer of Players”, as modified following the

intervention of the European Commission which, in its article 22, lays

down that recourse to arbitration is optional, any player or club

retaining the right to “seek redress before a (...) court”.

What’s more, in practice, it seems that just a small percentage of

disputes relating to this ruling are referred to civil courts, most dis-

putes ending up in the Court of Arbitration for Sport.

Without doubt, the fact that this rule was subject to amendments

required by the European Commission, prior to its entry into force,

and that its Community legality was thereby guaranteed, is not

unconnected with this state of facts.

In its judgment of 15 May 2006, ruling in the first instance on the

dispute between Sporting de Charleroi, backed by G-14, and FIFA

and UEFA, the Charleroi Commercial Court judged that: “... it is

clear that the ban issued by the second paragraph of article 51 (FIFA

statutes) on recourse to ordinary courts, only applies under the hypothesis

that an arbitration agreement in proper and due form would keep the dis-

pute out of these courts.

Any provision that would lay down a general ban on going before the

ordinary courts would, in fact, be contrary to public order and, conse-

quently, ought to be put aside by our court”

35

.

We may question UEFA and FIFA’s true motives, relayed via the

Arnaut report, for wishing so ardently that arbitration should be the

sole means of recourse against their decisions.

Does the answer not lie, once again, in the alleged desire of these

organisations to escape the application of Community law?

And from this perspective, it is not so much arbitration that has

garnered the favour of FIFA and UEFA but rather the fact - not by

chance - that the place of arbitration is Switzerland.

In fact, the Court of Arbitration for Sport, set up in Lausanne, is

an international court of arbitration in the sense of the federal Swiss

law on private international law of 18 December 1987.

Consequently, rulings given by the Court of Arbitration for Sport

are only open to appeal before the Swiss Federal Court, which main-

ly limits itself, when it comes to reviewing legality, to serious viola-

tions of international procedural public order.

This concept does not, however, include Community law, in par-

ticular, on competition, as explicitly judged by the Swiss Federal

Court, in a ruling of 8 March 2006

36

.

And so arbitration, provided that it is implemented, on an exclu-

sive basis, by a court of arbitration in Switzerland, incidentally makes

it possible to escape Community legal order.

According to article 1704 of the Belgian Judicial Code, sentences

given by a court of arbitration sitting in Belgium can only be subject

8

2007/3-4

ARTICLES

31 See the Wouters judgment.

32 For further information, see

www.g14.com

33 In this respect, see Stephen Weatherill,

“Is the pyramid compatible with EC

Law?”, The International Sports Law

Journal, 2005/3-4, p. 3 et s.; also in:

Stephen Weatherill, “European Sports

Law: Collected Papers”, ASSER

International Sports Law Centre/T.M.C.

Asser Press, The hague 2007, p. 259 et s.

34 EC press release IP/01/314, available at

this address:

http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesActi

on.do?refrence=IP/01/314 , in which the

Commission reiterates that: “arbitration

is voluntary and does not prevent recourse

to national courts”.

35 Unofficial translation. This ruling is

available on the Charleroi Commercial

court website: www.tcch.be .

36 Case 4P. 278/2005. See, in particular, this

link:

http://www.semainejudiciaire.ch/DATI/

DATI_JUR/2006/06_31.htm

2007/3-4

9

ARTICLES

to appeal before the territorially competent Court of first instance,

whose judicial review will mainly focus on conformity to public order.

Belgian public order does, of course, include Community public

order (in particular, therefore, articles 81 and 82 of the EC Treaty).

Where necessary, the Belgian judge may reverse the arbitration ruling

given in violation of Community law, i.e. refer to the ECJ any prelim-

inary issue that it may deem necessary.

The Court of Arbitration for Sport already has local chambers in

Sydney, in Australia, and in New York, in the United States. The

establishment of a headquarters within the European Union, for

example, in Brussels, would make it possible to reconcile arbitration

and Community legal order.

This would also mean that we would no longer be obliged to ques-

tion the sincerity of the attraction that arbitration holds for FIFA and

UEFA.

In conclusion, although certain measures may be envisaged on the

basis of current law (for example, certain practices mentioned by the

Arnaut report could be liable for exemption by category in the sense

of competition regulations) there is no argument to say that

Community law should be applied to the sports sector rather than to

other sectors, apart from under the specific circumstances already

acknowledged in some Commission decisions or Court of Justice rul-

ings

37

.

IV. Towards a change in Community Law?

As we have seen, the relationship between Community law and pro-

fessional sport is at the level of the EC Treaty itself. If, however, it

were to be necessary to amend the law in this matter, particularly to

institutionalise or consolidate the powers of the sporting federations,

new regulations or directives would not be enough, and it would

mean radical change in primary Community law, namely of the

Tr eaty itself, in some of its most fundamental principles.

There is currently no legal or political factor likely to lead to such

radical change. Let us look at the texts currently in circulation.

. Declaration of the European Council of Nice, - December .

The authors of the Arnaut report make much of this declaration “on

the specific characteristics of sport and its social function in Europe,

of which account should be taken in implementing Common poli-

cies”.

The authors admit that this declaration is not enforceable at law

because they claim that it should be transformed into positive law

38

but it should also be stressed that it is not even joined with the Treaty

of Nice, it contains no proposal to amend the Treaty agreed by the

Member States, even if, on certain points, the text echoes the view-

points of the sporting federations.

. European Parliament resolution of March on the future of pro-

fessional football in Europe

This resolution clearly originates from the Arnaut Report, since it

contains similar findings and suggests similar solutions.

This said, the resolution contains no formal proposal to change the

Tr eaty; it expresses a wish that the application of Community law to

professional football “does not compromise its social and cultural pur-

poses, by developing an appropriate legal framework, which fully

respects the fundamental principles of specificity of professional foot-

ball, autonomy of its bodies and subsidiarity”. This overlooks the fact

that the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice and the Commission

take this specificity into account since their decisions analyse the

objective of general interest which, provided that it is in proportion,

can inspire the rules of sporting federations and justify the restriction

of the fundamental freedoms or freedom of competition.

It overlooks that this same jurisprudence in no way undermines the

autonomy of professional sporting authorities acting as regulators, but

it is to be expected that, as an economic agent in a market represent-

ing billions of euros, the rules of the internal market and competition

should apply to them.

The Parliament also takes up the problem of legal uncertainty

resulting from an approach based solely on treating cases individual-

ly. We have already answered this argument, which applies to all eco-

nomic sectors and it is furthermore interesting to note that, according

to the European Parliament, it is not at all clear whether “the Union

of European Football Associations (UEFA) rule stipulating that teams

must contain a minimum number of home-grown players (...) would,

if it were reviewed by the Court of Justice, prove to be consistent with

Article 12 of the EC Treaty”. We feel that it is today in no way impos-

sible to make rules compliant with Community law.

We should also add that the European Parliament is careful not to

propose any automatic derogation of the competition rules and has

proved stricter with regard to UEFA and, above all, to FIFA, with

regard to the need to reinforce their internal democracy.

Last but not least, a resolution of the European Parliament obvi-

ously has no legally binding effect and the European Parliament has

no powers of decision or co-decision to change the founding treaties.

. Article III- of the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe

The Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe (which we now

know will never be ratified as such by the 27 Member States) includes

an article III-282 with specific reference to sport.

It is no exaggeration to say that this article does not propose any

change to Community law in the sense of the conclusions of the

Arnaut Report.

If the article provides that action of the European Union in matters

of sport should take into account “the specific nature of sport, its

structures based on voluntary activity and its social and educational

function”, this phrase gives no particular jurisdiction to the European

Union and, furthermore, concerns both amateur and professional

sport.

When that same article states that the intention of the European

Union to develop “the European dimension in sport, by promoting

fairness and openness in sporting competitions and cooperation

between bodies responsible for sports, and by protecting the physical

and moral integrity of sportsmen and sportswomen, especially young

sportsmen and sportswomen”, it in no way means that this action

could derogate the direct provisions of the Treaty as to freedom of

movement and competition.

Finally at the level of legislation which could be used to implement

article III-282, its paragraph (3) only allows the European Union to

adopt recommendations (which are not legally binding) or European

laws or framework laws to establish incentive measures, excluding any

harmonisation of the laws and regulations of the Member States. This

obviously implies that no exception can be made to the provisions as

to freedom of movement and competition.

We know that, since the signature of this Treaty establishing a

Constitution for Europe in 2004, it transpired that, despite eighteen

ratifications out of 27 Member States, the text of the Treaty had no

chance of being agreed by all Member States, which was indispensa-

ble to its entry into force. After a period of reflection, at the instiga-

tion of a very dynamic German presidency, the European Council of

June 2007 agreed on the text of a so-called “simplified” treaty, which

would include those parts of the Treaty establishing a Constitution for

Europe on which the 27 Member States could agree. The general idea

adopted in June 2007 was that, except for specific exceptions, the pro-

37 In our opinion, there is no question of

allowing sports federations to benefit

from the exemption provided for by arti-

cle 86 (2) of the EC Treaty which stipu-

lates that undertaking entrusted with the

operation of services of general economic

interest shall be subject to the rules con-

tained in the Treaty, in particular to the

rules on competition, in so far as the

application of such rules does not

obstruct the performance, in law or in

fact, of the particular tasks assigned to

them. Apart from the fact that this type

of tasks is generally entrusted to public

companies, we cannot really see that a

“service of general economic interest”

would be entrusted to sports federations.

Furthermore, let us remember that arti-

cle 86 (2) only results in the companies

in question being protected from the

application of Community law whilst

still being subject to administrative and

civil and, of course, Community courts.

38 See Arnaud Report p. 21: “In plain

terms, the aim of the current project is to

suppoyt and give practical effect to the

principles set out in the Nice Declaration,

in other words, to implement the

Declaration in sport and more particu-

larly in the specific case of football”.

2007/3-4

11

ARTICLES

posals in the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe should be

incorporated into the new treaty.

It is therefore not surprising to find in the first draft of the amend-

ed treaty, prepared by the Portuguese presidency on the basis of the

mandate from the European Council of June 2007, the practically

unchanged text of article III-282 of the Constitutional Treaty, which

was to become article 176 B of the EC Treaty. Nothing else on sport,

despite the publication of both the Arnaut report and the Resolution

of the European Parliament between the signature in 2004 and the

European Council of June 2007.

4. The “White Paper on Sport” of the European Commission published

on 11 July 2007

Far from the proposals in the Arnaut Report, the European

Commission recalled the relevance of existing jurisprudence, stressing

that the MECA-MEDINA and MAJCEN judgment made an impor-

tant legal point by rejecting the theory of the existence of “purely

sporting rules”, falling a priori outside the EC Treaty (and therefore

its articles 81 and 82) and affirming to the contrary that each sporting

rule should be studied case by case in the light of the provisions of

articles 81 and 82 EC.

In this context, quoting the principle of subsidiarity, the European

Commission refused to take an interventionist approach and - in the

main - intends to restrict itself to ensuring the respect of the basic

freedoms when necessary. It is appropriate here to quote the passage

which the Commission devotes to the “specificity of sport”:

“ Sport activity is subject to the application of EU law. (...)

Competition law and Internal Market provisions apply to sport in so far

as it constitutes an economic activity. Sport is also subject to other impor-

tant aspects of EU law, such as the prohibition of discrimination on

grounds of nationality, provisions regarding citizenship of the Union and

equality between men and women in employment.

At the same time, sport has certain specific characteristics, which are

often referred to as the “specificity of sport”. The specificity of European

sport can be approached through two prisms:

• The specificity of sporting activities and of sporting rules, such as sepa-

rate competitions for men and women, limitations on the number of

participants in competitions, or the need to ensure uncertainty con-

cerning outcomes and to preserve the competitive balance between clubs

taking part in the same competitions;

• The specificity of the sport structure, including notably the autonomy

and diversity of the sport organisations, a pyramid structure of compe-

titions from grassroots to elite level and organised solidarity mecha-

nisms between the different levels and operators, the organisation of

sport on a national basis, and the principle of a single federation per

sport;

The case law of the European courts and decisions of the European

Commission show that the specificity of sport has been recognised and

taken into account. They also provide guidance on how EU law applies

to sport. In line with established case law, the specificity of sport will con-

tinue to be recognised, but it cannot be construed so as to justify a gener-

al exemption from the application of EU law.

As is explained in detail in the Staff Working Document and its annex-

es, there are organisational rules that - based on their legitimate objectives

- are likely not to breach the anti-trust provisions of the EC Treaty, pro-

vided that their anti-competitive effects, if any, are inherent and propor-

tionate to the objectives pursued. Examples of such rules would be “rules

of the game” (e.g. rules fixing the length of matches or the number of play-

ers on the field), rules concerning selection criteria for sport competitions,

“at home or away from home” rules, rules preventing multiple ownership

in club competitions, rules concerning the composition of national teams,

anti-doping rules and rules concerning transfer periods.

However, in respect of the regulatory aspects of sport, the assessment

whether a certain sporting rule is compatible with EU competition law

can only be made on a case-by-case basis, as recently confirmed by the

European Court of Justice in its Meca-Medina ruling. The Court provid-

ed a clarification regarding the impact of EU law on sporting rules. It dis-

missed the notion of “purely sporting rules” as irrelevant for the question

of the applicability of EU competition rules to the sport sector.

The Court recognised that the specificity of sport has to be taken into

consideration in the sense that restrictive effects on competition that are

inherent in the organisation and proper conduct of competitive sport are

not in breach of EU competition rules, provided that these effects are pro-

portionate to the legitimate genuine sporting interest pursued. The neces-

sity of a proportionality test implies the need to take into account the indi-

vidual features of each case. It does not allow for the formulation of gen-

eral guidelines on the application of competition law to the sport sector”.

39

The Commission does not therefore propose any change to the

Tr eaty to meet the general central aim of the Arnaut Report, namely

the institutionalisation and consolidation of the authority of the

sporting federations.

Finally, the Commission:

- strongly supports the development of the “European Social

Dialogue”, and finds that “in the light of a growing number of chal-

lenges to sport governance, social dialogue at European level can con-

tribute to addressing common concerns of employers and athletes” and

that “a European social dialogue in the sport sector, or in its sub-sec-

tors (e.g. football) is an instrument which would allow social partners

to contribute to the shaping of employment relations and working con-

ditions in an active and participative way. In this area, such a social

dialogue could also lead to the establishment of commonly agreed codes