How the Internet

is fueling the

growth of creative

economies

Content

democratization

3Strategy&

About the authors

Jayant Bhargava is a Dubai-based partner with Strategy& and a

member of the firm’s communications and technology team. He leads

the firm’s work within the media and entertainment vertical and

focuses on the convergence of media, telecoms, and technology,

working at the intersection of traditional and digital media. His recent

client assignments include working with broadcasters, publishers,

advertisers, telecom operators, and technology players on strategy

and business models, M&A, and operating models, and supporting

government institutions on media sector policies and development

strategies.

Alice Klat is a Dubai-based manager with Strategy& and a member

of the communications and technology team. She leads consulting

assignments in the Middle East across the media, telecom, and

technology sectors. Her recent client work has included digital

transformation of traditional media companies such as broadcasters

and publishers, content and digitization strategies for telecom operators,

and growth strategies for technology service providers.

4 Strategy&

Contents

Methodology 5

Acknowledgments 6

Highlights 8

Introduction 10

Chapter 1

Japan: Growth in a contracting economy 38

Chapter 2

India: Digital infuses innovation and diversity 48

Chapter 3

Australia: The revival of content 63

Chapter 4

South Korea: Opening the creative sector to the world 80

Chapter 5

Thailand: Transition to digital creative content 100

Conclusion 113

Endnotes 115

5Strategy&

Methodology

The amount of digital content created, exchanged, and consumed is

growing by the day across the world, and because the Internet has

democratized access to creation and distribution tools, boundaries

between professional and amateur content are blurring across all

parts of the creative sector. The objective of this report is to provide a

comprehensive view of the eect of the Internet on content providers

and distributers, emerging artists, and consumers in five very dierent

countries— Australia, India, Japan, South Korea, and Thailand. We

selected these countries because they feature highly varying levels of

Internet connectivity, infrastructure development, and media reach.

Studying the commonalities and dierences among them contributes

to an understanding of how the Internet can bring value to the creative

sector regardless of a country’s institutional and technological

framework.

We analyzed the impact from the consumer perspective as well as from

the creator and industry perspectives, providing a dierentiated

perspective on each player.

Our methodology combined desk research with one-on-one interviews

with representatives of leading companies in each of the five countries.

Our desk research was based on respected industry sources such as

PwC’s Global Entertainment and Media Outlook, Ovum, and the World

Bank, to name just a few. We assessed the impact of the Internet on

both a quantitative and a qualitative perspective. Some of the key

quantitative figures we analyzed were the market size and growth of

the creative sector, the evolution of consumer time spent across media,

and indicators of each country’s degree of digitization. Examples

of qualitative factors we assessed include creative industry players’

business models and evolution, and strategies for integrating traditional

and digital media, as well as market dynamics and competitive

strengths.

6 Strategy&

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the central role of numerous participants in

meetings and interviews across Australia, India, South Korea, and Thailand.

Without their expert insights, the study would not have been possible in the

present form.

We thank the following individuals and organizations for their time, insights,

and thoughts.

88KeysToEuphoria (India)

A.ble (South Korea)

AIB (India)

Alan Adcock (Thailand)

Allens law firm (Australia)

Arirang TV (South Korea)

Australian Digital Alliance (Australia)

BKI (South Korea)

Baker & McKenzie, Sydney

(Australia)

Bandi/Luni’s (South Korea)

Courtney Barnett (Australia)

Beamafilm (Australia)

Bookmoby (Thailand)

BuzzBean (South Korea)

Casbaa (APAC)

K. Chaiyan (Thailand)

Channel 7 (Thailand)

Choc Chip Channel (Thailand)

Chung-Ang University (South Korea)

Crikey.com.au (Australia)

Dotty (South Korea)

Draw with Jazza (Australia)

Dymocks (Australia)

Electronic Frontier Foundation

(Australia)

Flipkart (India)

Gaana (India)

GrabTaxi (Thailand)

Hearst-Bauer Media brands

(Australia)

iFlix (Thailand)

I Quit Sugar (Australia)

KT Olleh Music (South Korea)

Khajochi (Thailand)

KledThai (Thailand)

Korea’s Game Association

(South Korea)

Loen Entertainment (South Korea)

Mahidol University (Thailand)

Manodio (South Korea)

Mint (India)

Mun FM (Thailand)

NHN (South Korea)

National Programme on Technology

Enhanced Learning (NPTEL)

(India)

New Media Communication

(India)

Nexon (South Korea)

Olleh Games (South Korea)

Ookbee (Thailand)

OpenNet (South Korea)

Ormschool (Thailand)

Pandora Australia and New Zealand

(Australia)

7

Pantip (Thailand)

Phonographic Performance

Company of Australia

(Australia)

Rajshri Entertainment (India)

Rich World Record Label

(South Korea)

SBS (South Korea)

SM Entertainment

(South Korea)

Screenrights (Australia)

Shemaroo Entertainment (India)

SketchShe (Australia)

Sony Music Entertainment Australia

(Australia)

Southern Cross Austereo (Australia)

State Library of New South Wales

(Australia)

Thai Rath (Thailand)

TrueVisions (Thailand)

Turner Asia (Thailand)

Universal Music (Australia)

Van Vuuren Bros (Australia)

YG Entertainment (South Korea)

YoBoHo (India)

Whacked Out Media (India)

This report was financed by Google Inc., and independently researched

and written by Strategy&, PwC’s strategy consulting business. It draws on

expertise from Strategy&’s communications, media, and technology practice

and from its digitization team, as well as on academic and public research,

public information, and primary research.

8 Strategy&

Highlights

• The growth of digital content, and especially paid digital

content, is driving the growth of the creative sectors in all of

the five countries we studied. And it is growing more rapidly than

the nominal GDP in most of these markets. In fact, in Australia,

South Korea, and Japan, all of the growth in creative industries

is being driven by digital media. Digital media contributed

$14.5 billion in revenues across these three markets from 2012

through 2014.

• People are spending more time consuming both the traditional

and digital output of the creative sector, almost entirely due to

the Internet. Time spent consuming content has been increasing

across all five countries in our study as people spend a greater

portion of their leisure and entertainment time with creative

content. In Australia, for instance, people spend an average of 9.7

hours a day consuming content,

1

up from six hours a day four years

ago, with almost half of this time being spent on the Internet.

Similarly, growth in time spent consuming content on the Internet

ranges from 5 to 11 percent annually across Thailand, India, and

South Korea.

• We are witnessing the rise of a consumer-creator model that has

broken down the barriers to the creation and distribution of content.

Consumers are increasingly participating in infotainment and video

content creation through forums, blogs, and social networks, and

social media platforms have enabled users to convert their passions

into careers by making their work accessible to millions of users

around the world.

• Digital content is at the heart of the emergence of a cultural

renaissance thanks to the opportunity for niche content creators to

distribute their products on the unlimited shelf space of the Internet.

Broadcasters, publishers, and other traditional media distributors

that were constrained by limited space for their content oine have

seen their business models disrupted.

9Strategy&

• Digital is also enabling the spread of content across large and

previously underserved populations, especially in markets such as

India, where a vast majority of the population does not have access

to traditional media such as newspapers, books, and pay TV. These

populations are now able to access content on the Internet, in many

instances through their mobile phones.

• The export market for content from these countries has grown

rapidly, as the Internet permits easier access to international

markets, yielding significant revenues. Content creators and

distributors across all creative sectors now have access to previously

untapped markets.

• Emerging artists are benefiting from open, instant, and, in many

cases, free access to a critical mass of users via online distribution

platforms, as well as from dedicated platforms providing assistance

in production, distribution, monetization, and audience

development.

• Local content consumption is rising, as exemplified in Australia,

where short-form audio/video content is much more popular on

digital platforms than on long-form box oce platforms. Local

YouTube artists in Australia are capturing and engaging with a much

larger share of the country’s audience than is the box oce, where

just one of the top 20 movies for each year between 2010 and 2015

was local.

• Content majors can now access larger audiences while increasing

loyalty and tailoring their oerings to user preferences. They also

benefit from cost-eective access to new talent.

• Distributors are monetizing digital, international, and long-tail

content and building more agile and cost-eective new business

models. Social media has also allowed them to capture more

audiences and increase content usage.

10 Strategy&

Introduction

As of July 2016, almost 3.41 billion people around the globe

(46 percent of the world’s population) were connected to the Internet.

The Internet has reduced the distance between them, allowing for

instant communication and exchange of data, news, opinions,

information, entertainment, and more. In so doing, the Internet has

transformed many industries— from telecommunications and finance

to retail and travel. The five creative sector industries that we consider

in this report have been no less transformed.

Indeed, the creative sector has become a prime example of the

convergence of the digital and the non-digital. The line between a TV

show or a newspaper article and its digital extensions— everything

from online videos to apps— is fading away, even as the line between

artists and audiences is fast blurring as well.

The benefits of the Internet for the creative sector, however, have so

far been unevenly distributed. Some industries, such as gaming,

have rapidly reaped extraordinary rewards; others, including music,

newspapers, and magazines, which have been slower to adapt to

digital models, have experienced limited growth. However, there is

no doubt that for the sector as a whole, the Internet has unleashed

an unprecedented burst of creativity— artistic, technological, and

commercial. And the biggest beneficiary of all? The consumer.

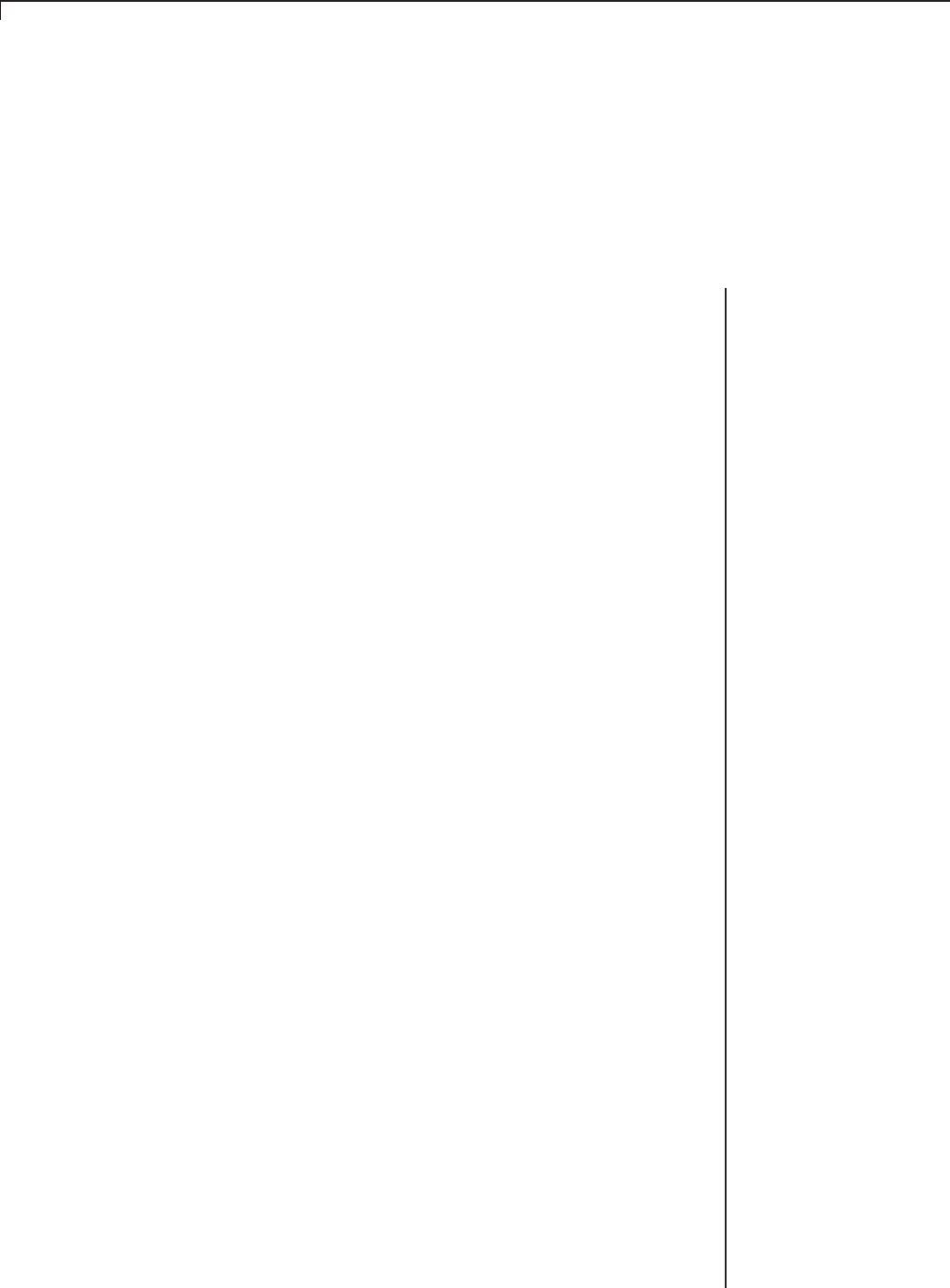

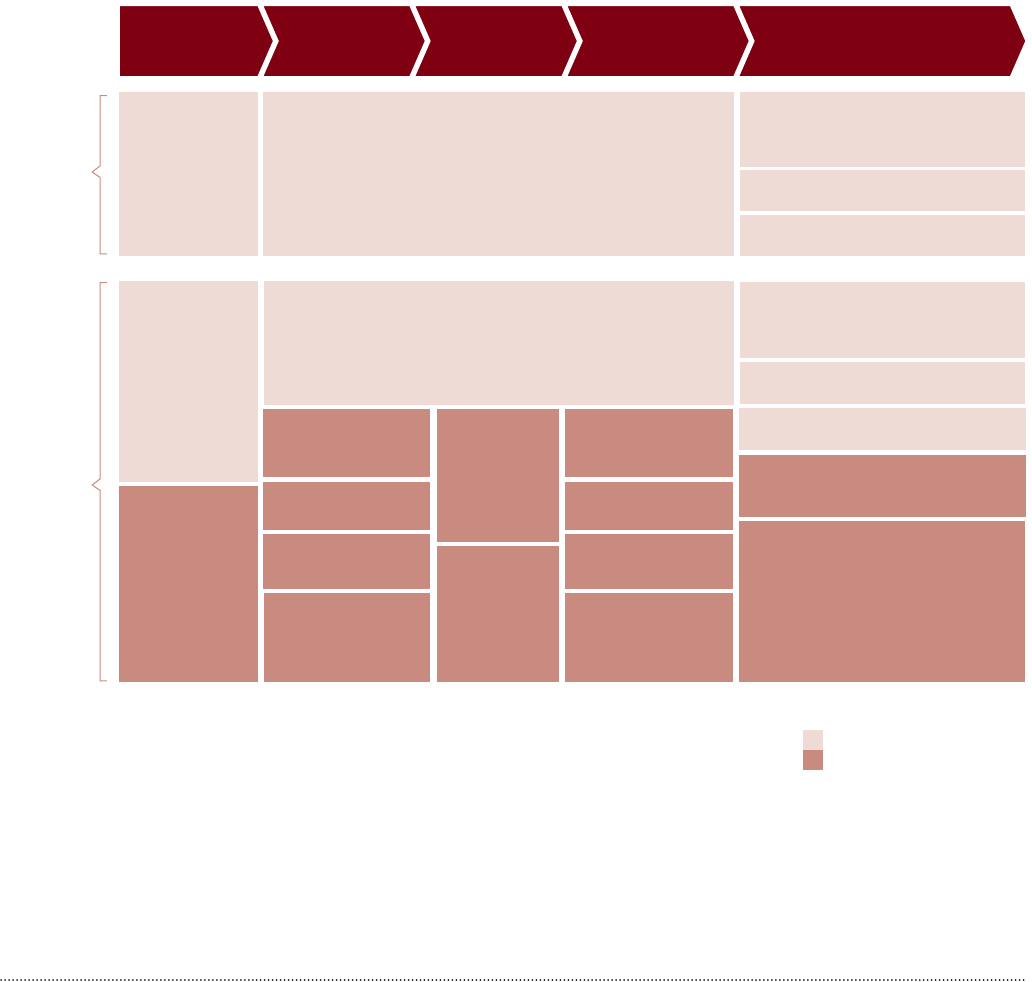

Defining the creative sector

There is no single, uniform definition of “the creative sector.” This

report defines it as all creative eorts directed at consumers, within the

larger information and entertainment business, where the works are

designed to generate a for-profit commercial return. The report focuses

on five industries— video (film and television), periodical print

publishing (newspapers and magazines), book publishing, electronic

gaming, and music— all of which depend to varying degrees on

copyright to support the generation of revenue, from both digital and

non-digital sources. Ultimately, the creative sector should be seen as

11Strategy&

part of a larger social system that includes, at the outer layer, the

culture and language of a country or region on which all creative

production is based (see Exhibit 1).

Source: Strategy& analysis

Exhibit 1

The creative industries defined

The study focuses on the largest end-user-directed creative industries

Culture and language

Denition of focus sectors

Description

Creative ecosystem

– Organized creative industries,

directed toward businesses

as well as individuals

– Overall environment of

people in a local culture/

country (e.g., language)

– Unorganized creative

production (e.g., blogs)

– Organized creative industries,

mostly profit-oriented

– End-user-directed creative

industries in the larger

information and entertainment

business

– Enabling industries that

support the distribution and

monetization of creative

content (e.g., ad sales)

Enabling industries

Organized creative industries

Creative industries in focus:

Film and television

Periodical print publishing

Book publishing

Music

Gaming

12 Strategy&

This definition explicitly leaves out the live performing arts and sports

events, fine arts such as painting and photography, and any B2B-

directed creative production, including product design and architecture.

Moreover, although the creative sector is supported by numerous

“enabling industries” such as advertising agencies, search engines,

and social media, these providers are also excluded from our definition

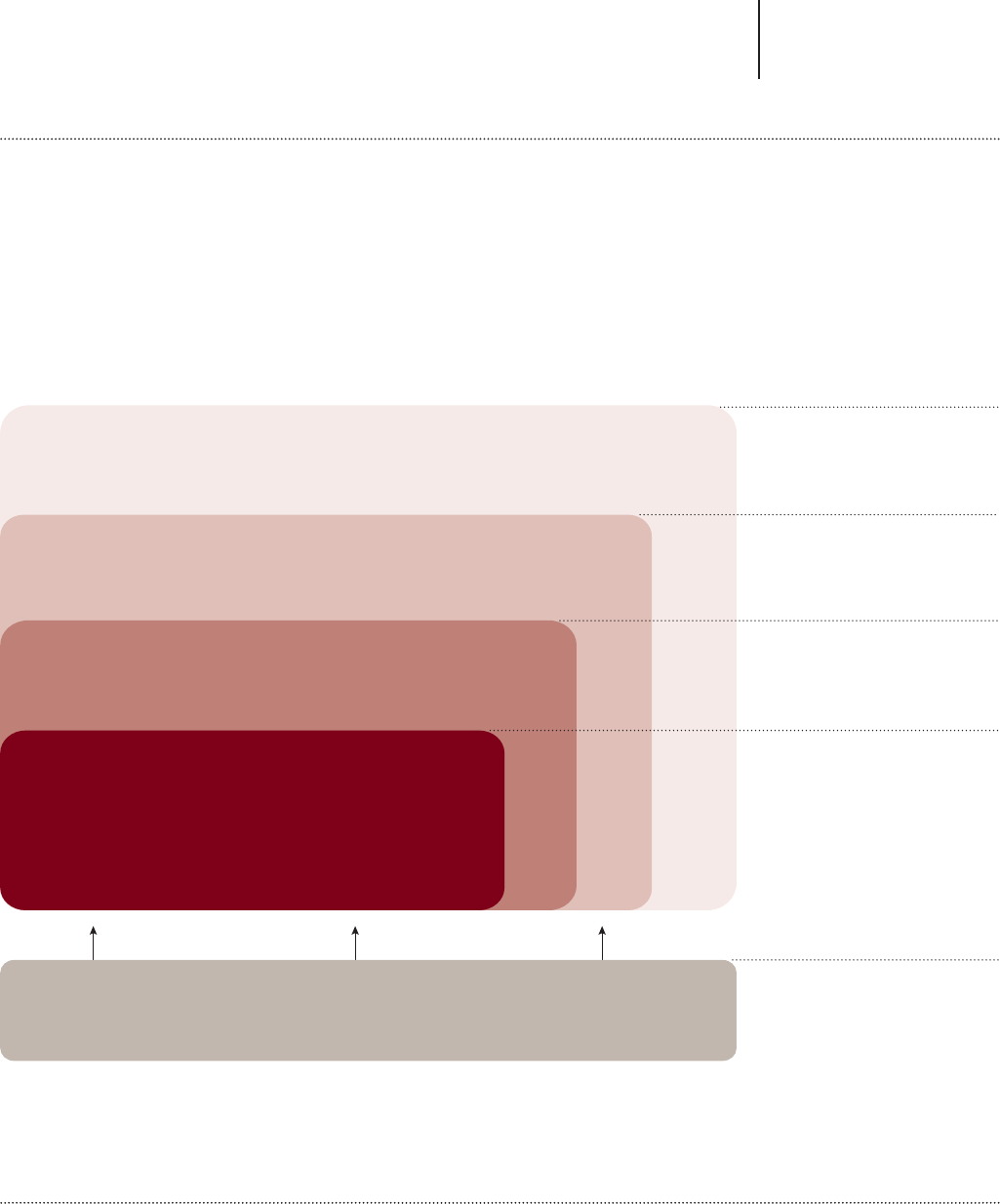

(see Exhibit 2). Thus, we include advertising-supported media, such as

television and online newspapers, but not the advertising industry itself.

Source: Strategy& analysis

Exhibit 2

Our focus industries across the value chain and platforms

Videos

(television, film)

Music

(radio, recorded music)

Books

Print

(newspapers,

magazines)

Gaming

Creation

Production

Distribution

Consumption

Creative industries

Value

chain

Delivery

platforms

Traditional

(offline)

PC

Mobile

Tablet

Set-top

box

13

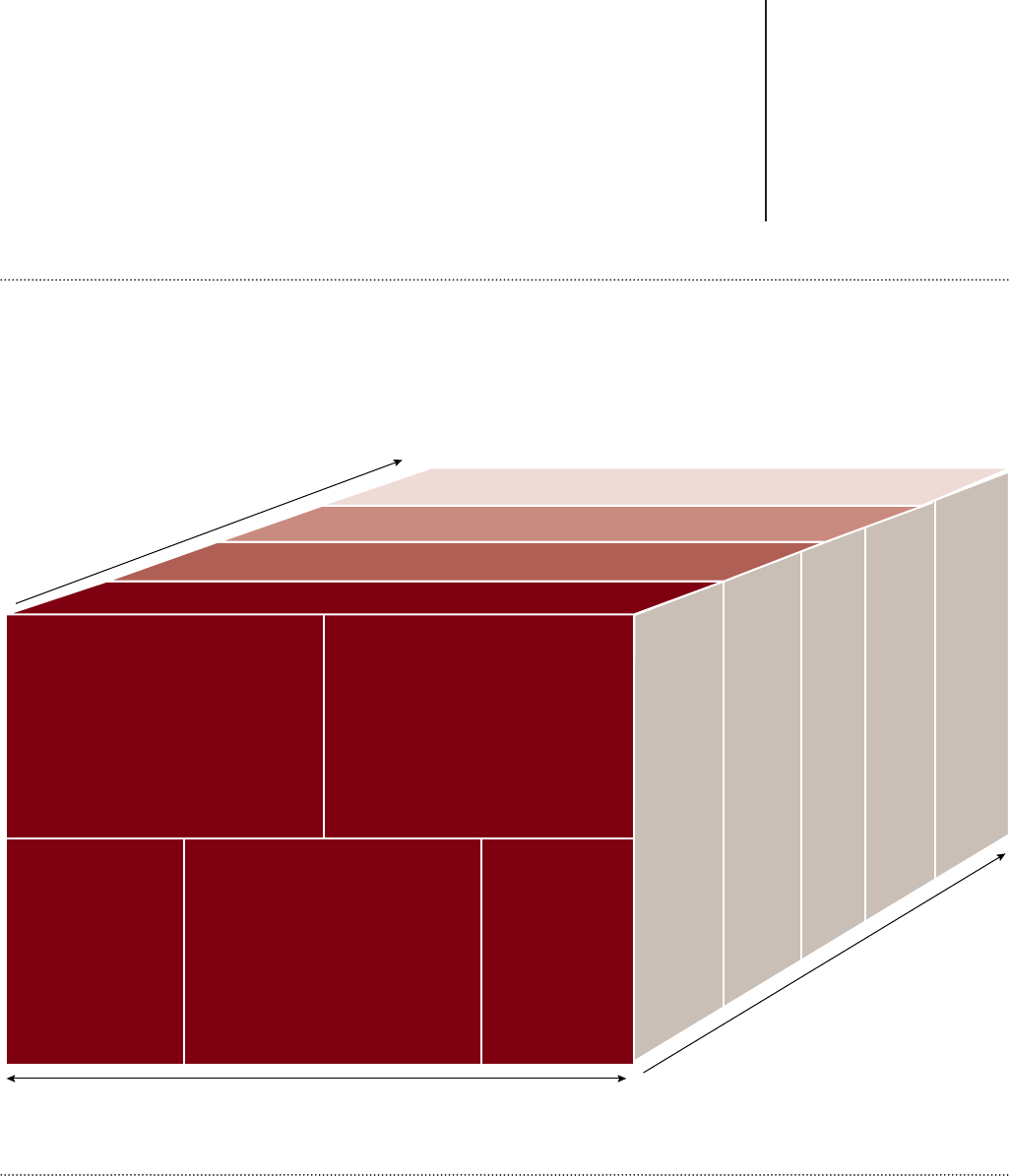

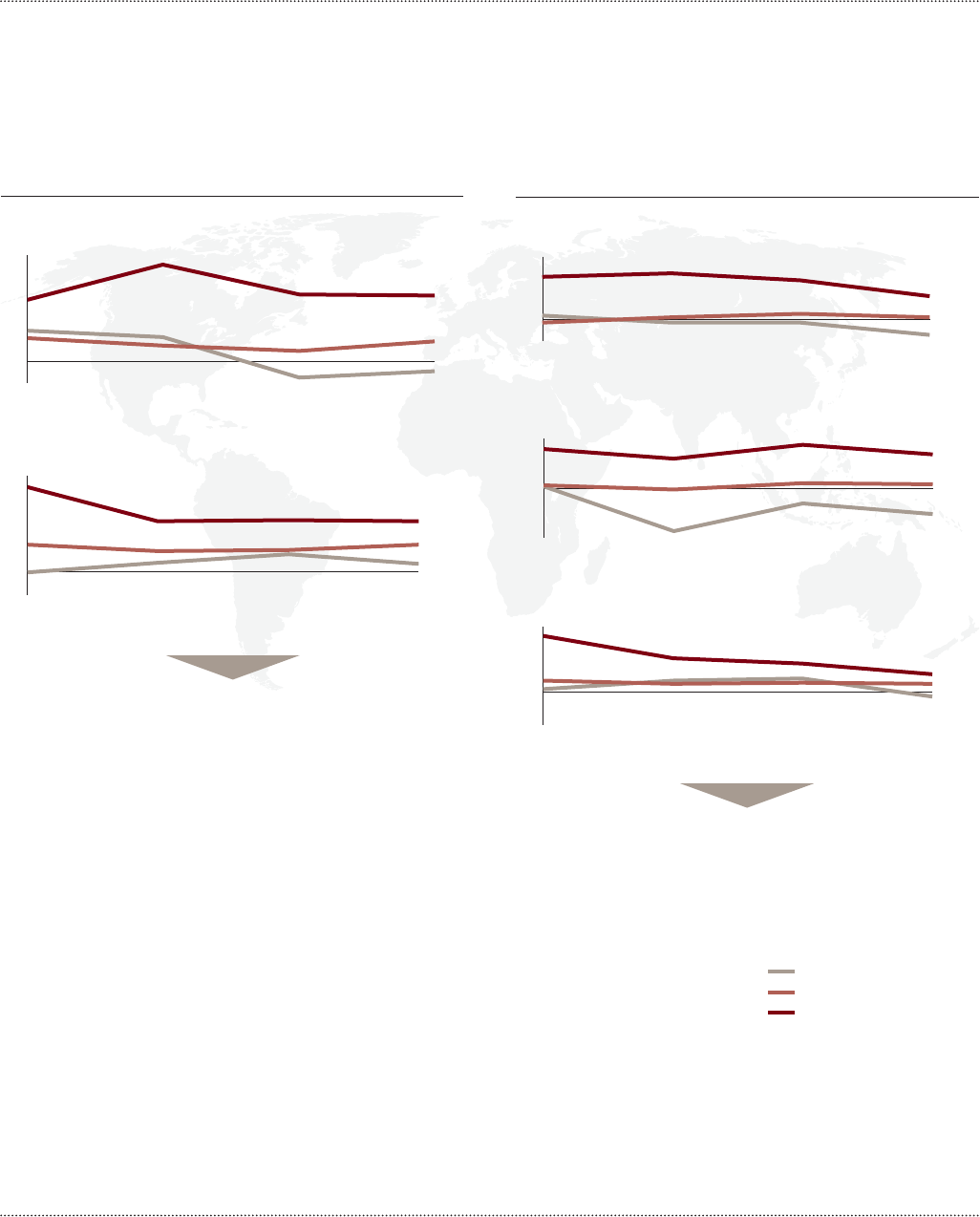

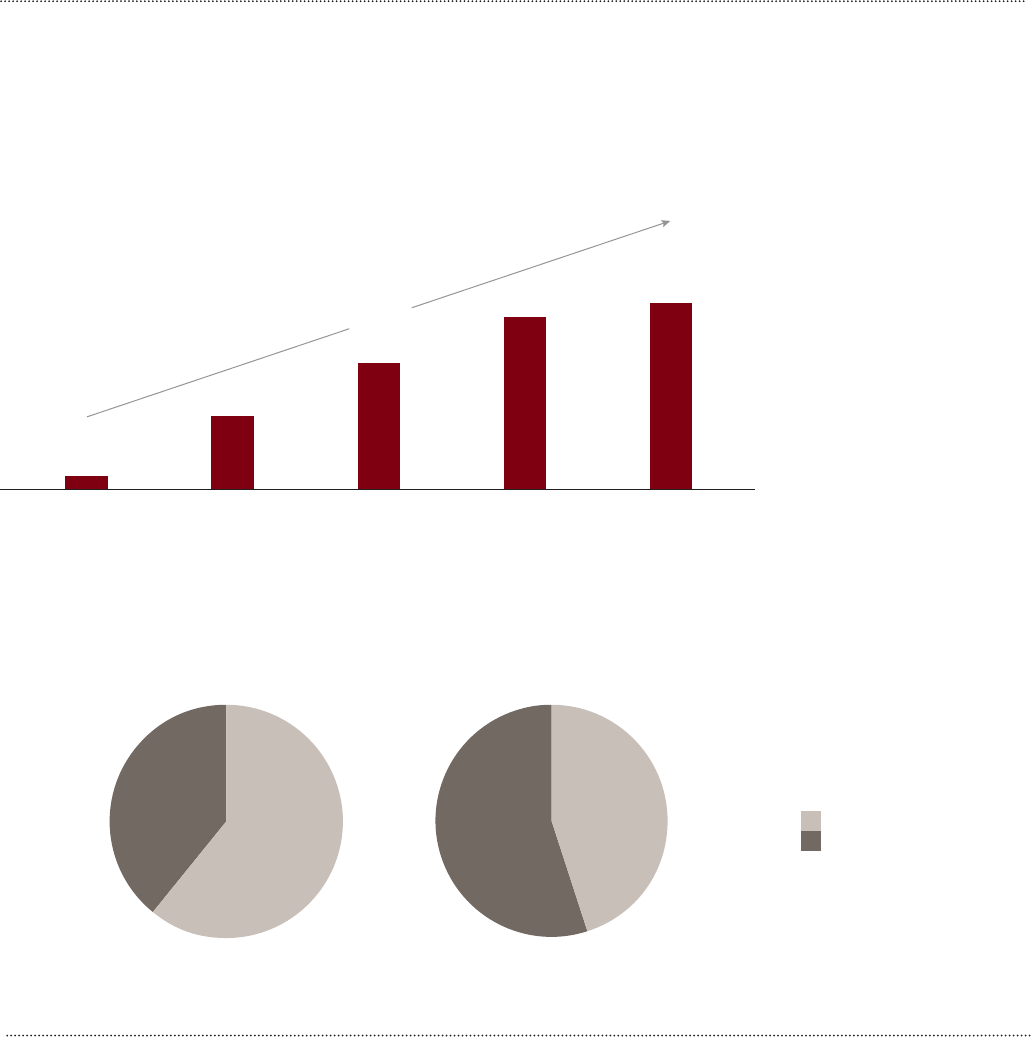

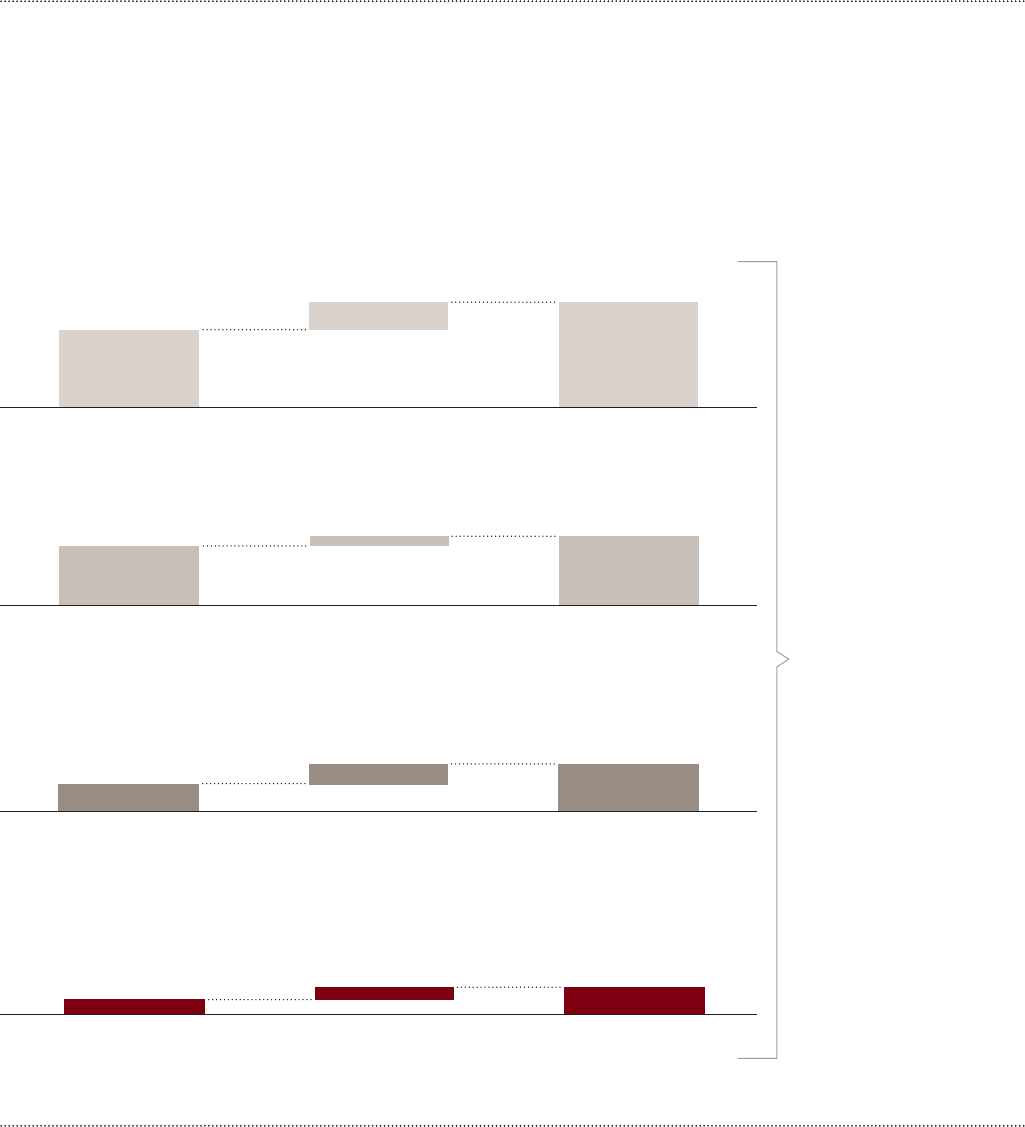

Stages of Internet evolution

To study the many dierent ways the Internet has aected the creative

sector, we selected five countries, at varying stages in the process of

digital evolution. Specifically, we classified those countries into four

categories based on their level of traditional media reach and Internet

connectivity. Traditional media reach— the level of penetration of

traditional content distribution platforms such as television and print

into a market’s households— allows us to understand the accessibility

of content in each country without the Internet. Connectivity is

measured by the level of penetration of fixed and mobile broadband and

smartphones across the market’s population (see Exhibit 3, next page).

These are the four stages we identified.

• India is a next-generation market. It features low fixed broadband

and smartphone penetration, and its level of traditional media

distribution is not particularly strong. However, high and increasing

mobile broadband penetration— 73 percent in India— is vastly

improving the ability of consumers to access informational,

entertainment, and educational content and fast-tracking the

growth of the country’s creative sectors overall.

• Thailand is in the transitional phase, having reached a more

developed state of Internet connectivity. Fixed and mobile broadband

connections and smartphone penetration are at acceptable levels,

and traditional media distribution is strong. As such, the Thais

benefit considerably from the tools required to consume creative

content both through traditional means and on digital devices.

• Japan is fully equipped for digital, as is Australia in its major urban

areas (Australia’s more remote communities fall more closely into the

transitional stage). These markets enjoy highly developed fixed,

mobile, and smartphone penetration that allows their people to

consume high-quality, high-resolution content.

• Finally, in hyper-connected South Korea, digital is in the population’s

very DNA. South Koreans are among the largest consumers of digital

creative content in the world, and can access ultra-high-resolution

videos and games anywhere, anytime, and anyhow.

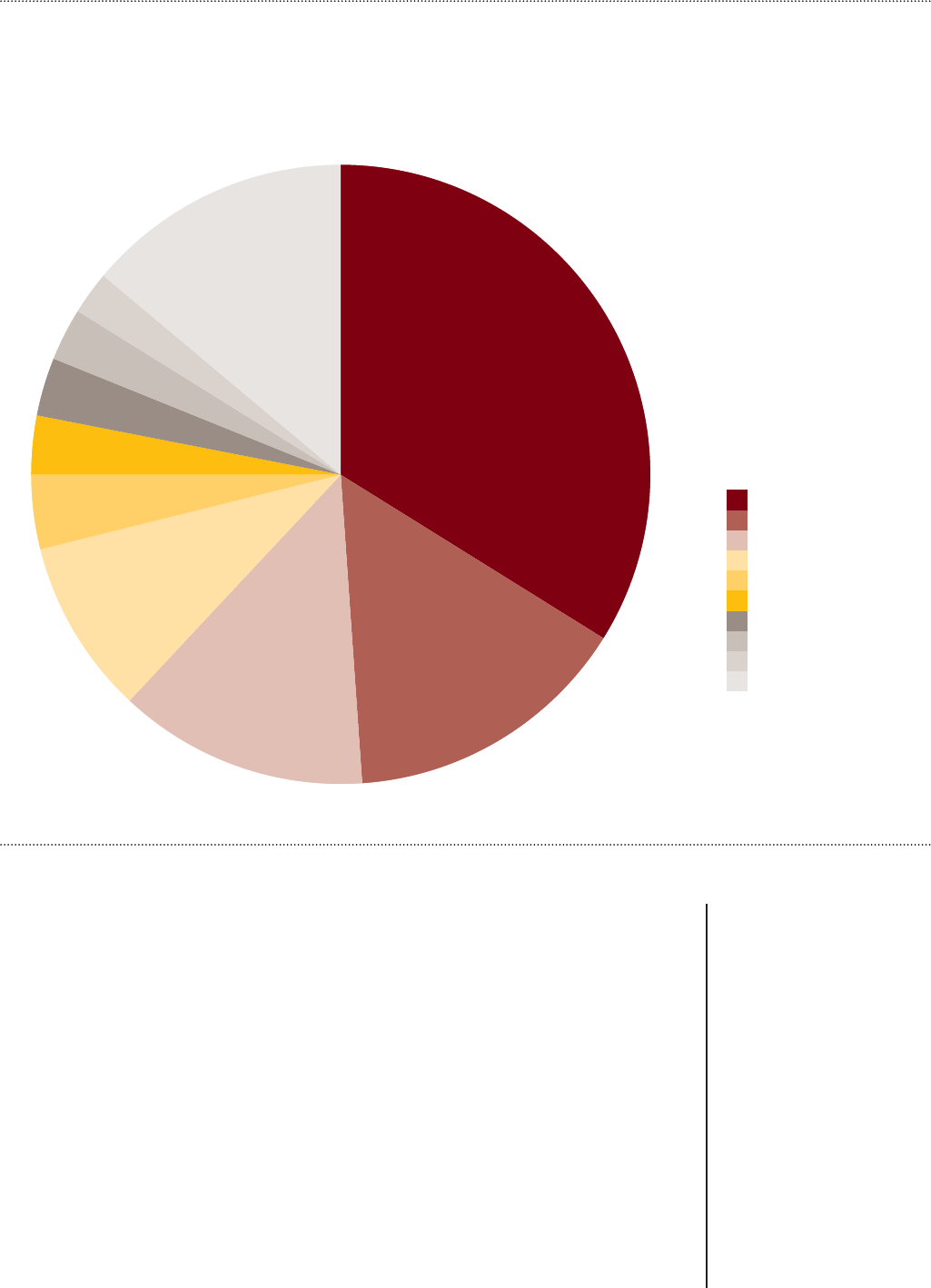

Overview of each creative sector

The impact of the Internet on each of the five creative industries has

been uneven. Although video remains the largest creative sector in

terms of revenue, the gaming sector has been the largest contributor to

14 Strategy&

1

Based on the average

of fixed and mobile

broadband penetration and

smartphone penetration.

2

Based on the maximum

penetration of TV and

newspaper per household.

3

Represents digital media

size per connected Internet

user.

Source: Informa Telecoms;

WBIS; Strategy& analysis

Exhibit 3

Internet maturity and media penetration

Transitional

digital markets

Digital

DNA

markets

Next-generation markets

Low smartphone

penetration (below 10%)

Medium smartphone

penetration (10%–50%)

High smartphone

penetration (above 70%)

Nascent Developing Mature

Medium

Penetration of traditional

media 20%–60%

High

Penetration of traditional

media above 60%

Low fixed broadband

penetration (below 10%)

Medium fixed broadband

penetration (10%–50%)

High fixed broadband

penetration (above 70%)

Digital media size

3

Focus countries’ stages of Internet evolution, 2015

Digital-equipped

markets

South

Korea

AustraliaJapan

India

Thailand

Traditional media

reach, 2015

2

State of Internet connectivity, 2015

1

15

the growth of creative content. Across all five countries between 2011

and 2015, gaming, mainly driven by digital, has been growing most

rapidly, at 13 percent per year. Video and books have been growing at

4 and 1 percent per year, respectively, while music and print have each

dropped 1 percent.

2

(These numbers combine both digital and non-

digital content.) A closer look at each industry explains why.

Video. Traditional platforms such as satellite and cable TV remain

the dominant sources of revenue coming from creative content, while

revenues from digital video content have not yet reached their full

potential across all five countries. Still, viewership of online and mobile

videos is soaring. Internet TV platforms have already had a significant

impact, increasing the breadth of content oered and providing the

ability to upload content, both professional and user-generated. Interest

in short-form content (on sites such as YouTube, Vine, and Dailymotion)

is booming, while short- and long-form premium content (films and TV

series) is increasingly available at aordable prices on so-called over-

the-top platforms such as Netflix and Hulu that carry their data over

traditional telecom networks. For linear TV channels, dual screening

and multi-platform experiences have become a must to retain and

engage a highly connected audience.

Already, many broadcasters have expanded their revenues by following

their consumers online. They have successfully introduced a variety of

new business models to make money from their content and create new

experiences, and such innovations will continue to drive the industry’s

growth. The digital landscape is also allowing for the emergence of

niche video producers bringing non-mainstream content to audiences,

thanks in part to a growing ecosystem of players oering support, from

production and funding through to distribution.

The revenue contribution from digital TV remained low in all markets

in 2015, varying from just 1 percent of total video revenues in Thailand

to 5 percent in Japan. Going forward, digital videos, including TV and

home entertainment, are expected to fuel the overall video industry

growth at annual rates between 16 and 25 percent from 2015 to 2020.

3

Periodical print publishing. The Internet has had a huge and in many

ways disruptive impact on periodicals, which continue to experiment

with new ways to extract value from digitization. Although demand for

news in general has been on the rise, how people consume it is changing

fast. Younger people typically don’t consume news in print or on TV, and

are much more likely than people over 45 to get their news through

mobile devices and social media.

4

This suggests that traditional news

providers should be able to capture more value if they can develop truly

appealing digital ecosystems and innovative business models.

Although

demand for

news in general

has been on the

rise, how people

consume it is

changing fast.

16 Strategy&

In countries with more mature digital capacity, traditional news-

oriented business models are increasingly shifting from a platform focus

to a content focus: People get their news from multiple formats— from

TV and newspapers to publishers’ websites, citizen journalism sites such

as the Hungton Post, blog sites like BuzzFeed, and, increasingly, social

media networks (Facebook, Twitter, and others) and mobile apps.

Periodicals at a global level have seen revenues and profits decline, but

are now experimenting with new business models and revenue streams.

The five markets in our study have been facing this decline at dierent

intensities: The drop has been strongest in the digital DNA and digital-

equipped markets. The Australian newspaper industry has seen annual

revenue losses of 3 percent between 2011 and 2015; in South Korea and

Japan, the industry has lost around 1 percent per year. Thailand, which

is in the transitional phase, witnessed a stable growth of 0.5 percent per

year. In next-generation markets, however, digital has not yet disrupted

the print players; India has seen annual growth of 4.8 percent.

5

Several studies have assessed the role of each media platform across

each step of the news consumption journey. They have found that

discovery increasingly occurs on social media or through a publisher’s

breaking-news app. News amplification occurs on social media and

forums, while validation and investigation occur only on the most

credible publishers’ branded sites.

Print publishers have great assets with their established brands and

existing content capabilities. The future success of print media

businesses will depend on their ability to continuously create relevant

consumer experiences that utilize their unique strengths and the

perceived credibility of their brands to more eectively leverage their

existing assets.

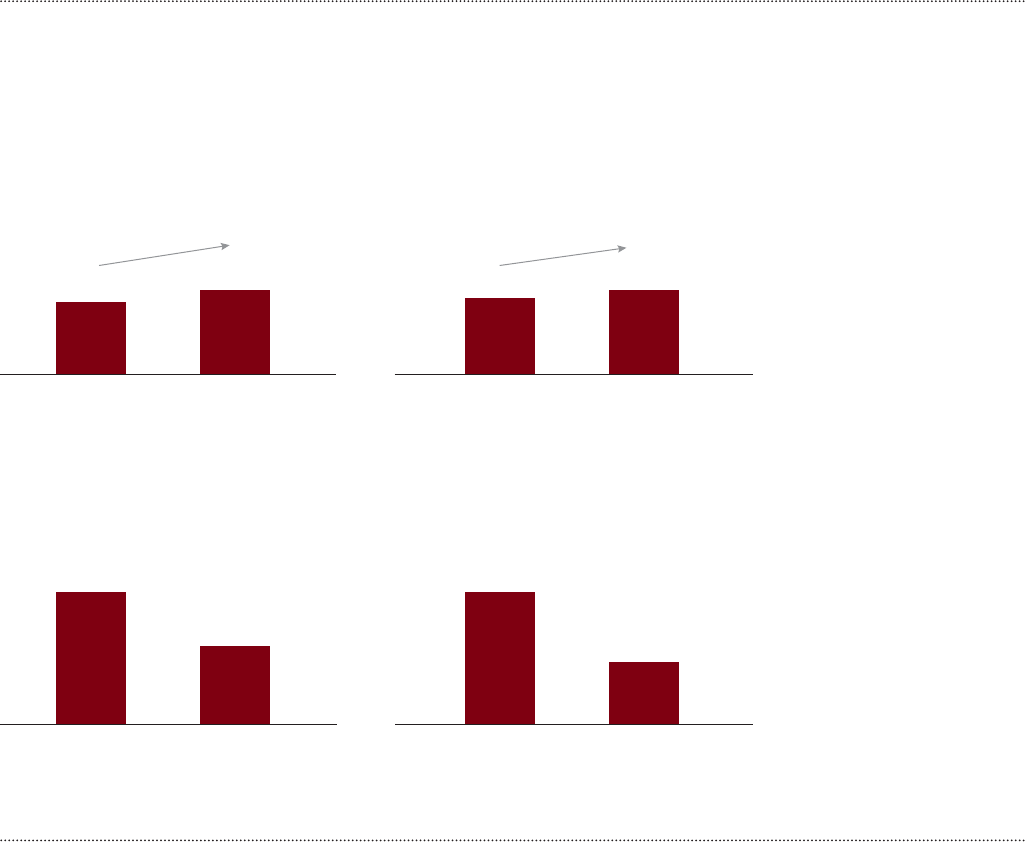

Book publishing. This will be the next industry to be fully

revolutionized by digitization. Up to now, the financial impact on books

in the countries we studied has been small, but that, too, will change.

Revenues for physical books are growing or stable in all five of our

countries, and the share of digital revenues was still only about 15

percent in 2014. South Korea is at the upper range of digitization, with

e-books contributing a 24 percent share of sales in 2014, while next-

generation markets such as India are still hovering around a 2 percent

share.

6

Traditional publishers in every market are moving online to oer larger

book libraries and the convenience of home delivery, while also

distributing hard-copy editions. The Internet has become a supplement to

traditional book retailers, which use it to drive trac to their bookstores,

acquire new customers, and promote their brands and products.

17Strategy&

While traditional bookstores are increasing their focus on online

distribution, book aggregators and e-readers such as Amazon’s Kindle,

Apple’s iBooks, and Google Play Books are entering the e-books market

in Asia-Pacific. As a result, the number of e-book releases in Japan has

increased from 260,000 in 2011 to more than 1 million in 2014. This

development oers consumers a large range of books that are easily

carried, are aordably priced, and can be stored in large numbers.

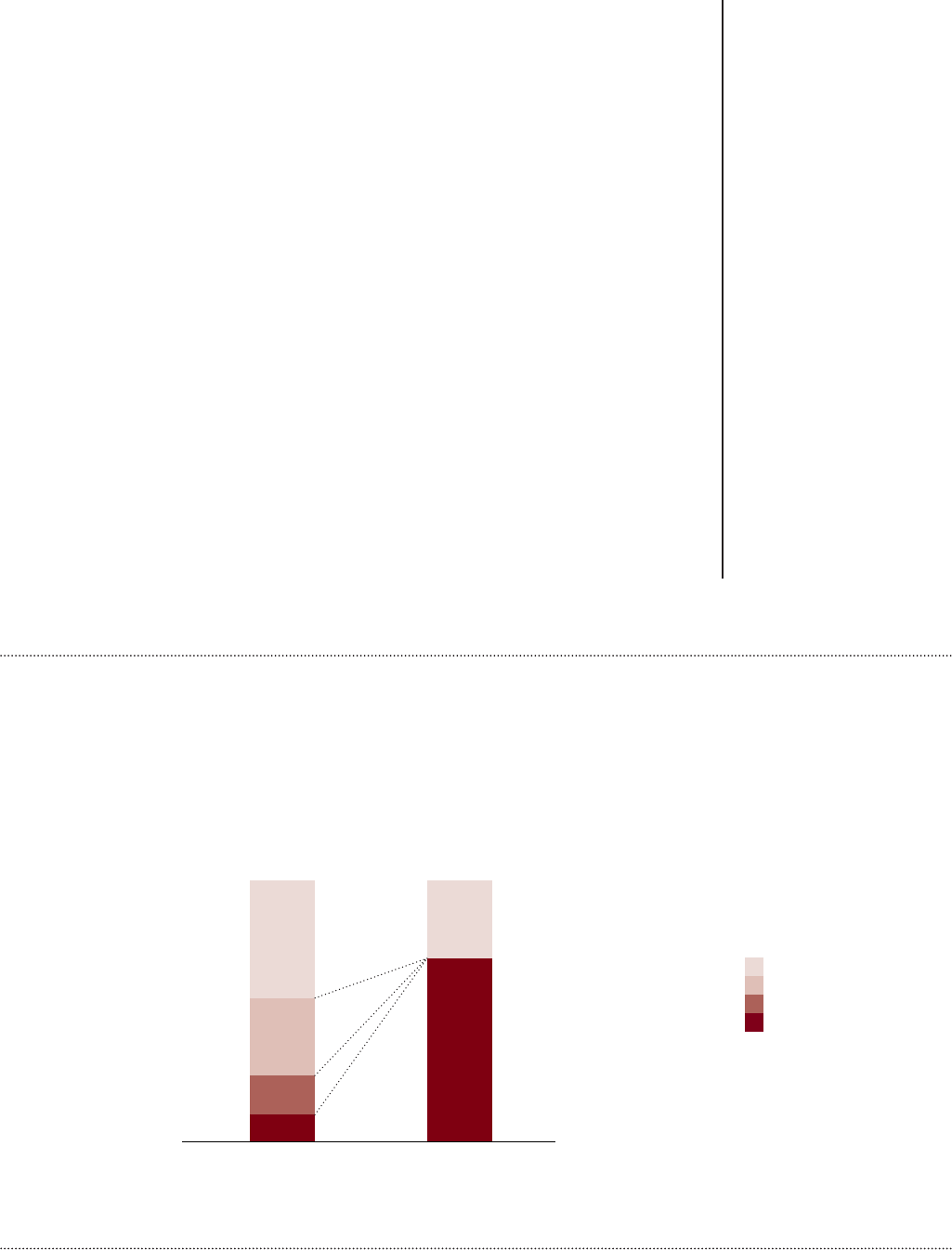

The new phenomenon of self-publishing is also emerging in the form of

platforms that nascent writers can use to publish their work, gain access

to a community of readers with whom they can interact, and leverage

an end-to-end publishing solution from content preparation to storage

and delivery to billing. In Thailand, for example, authors who self-

publish capture 70 percent of the revenues from sales, compared with

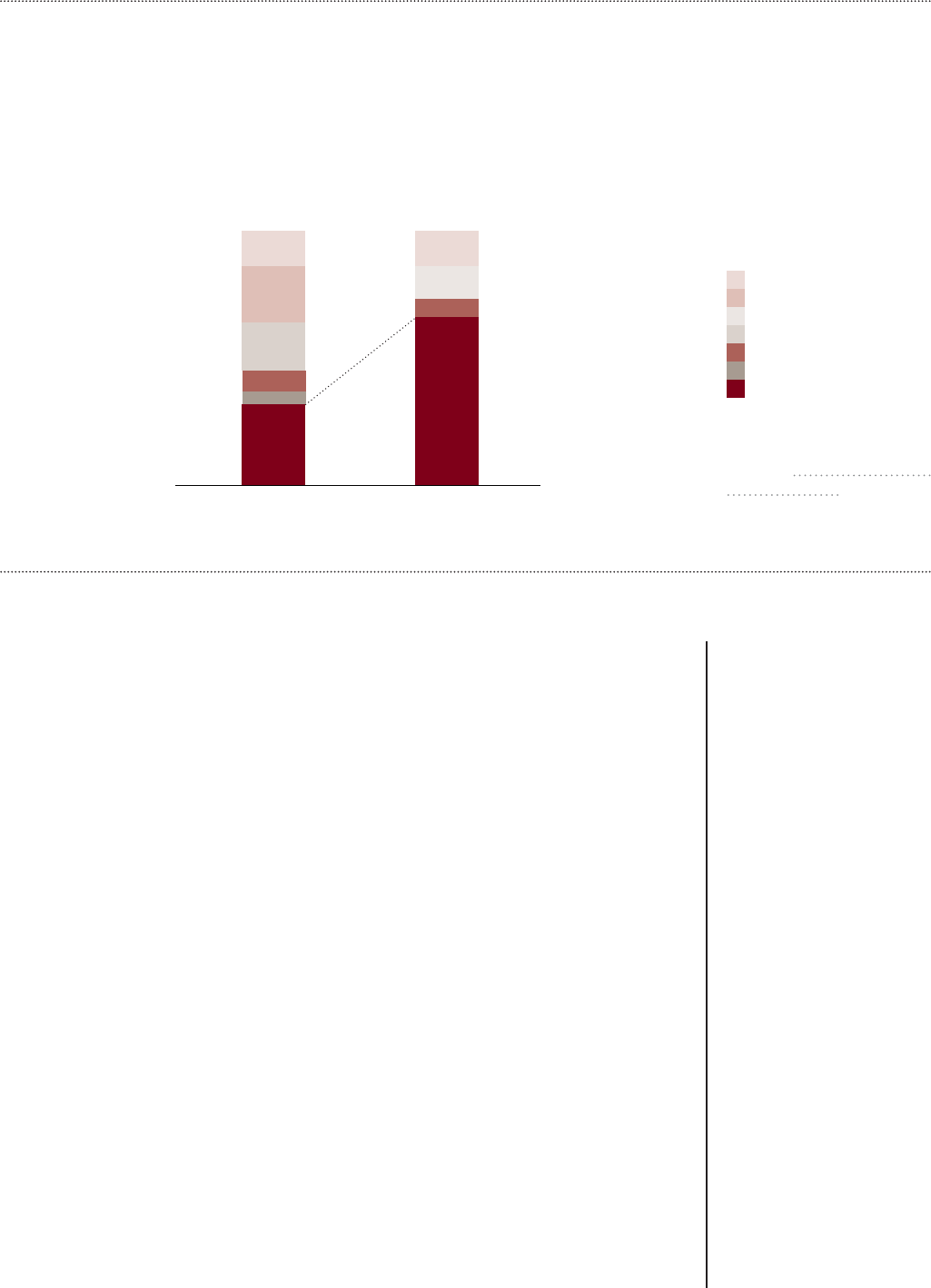

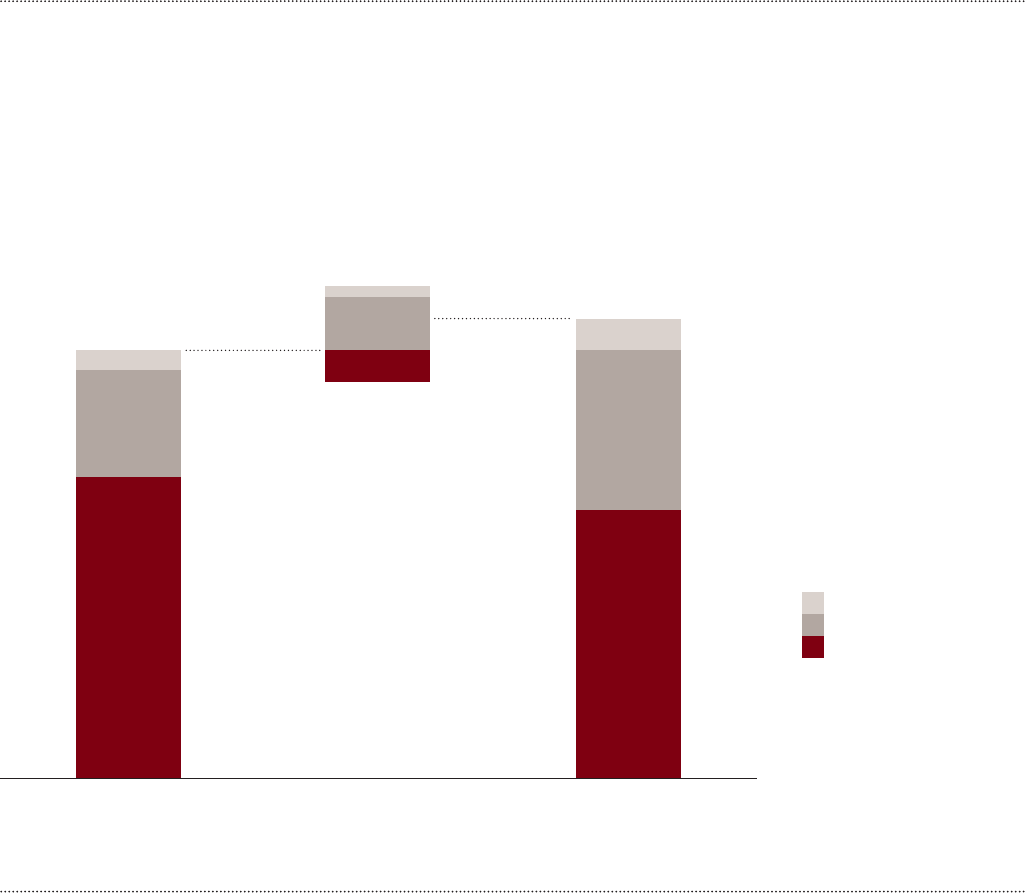

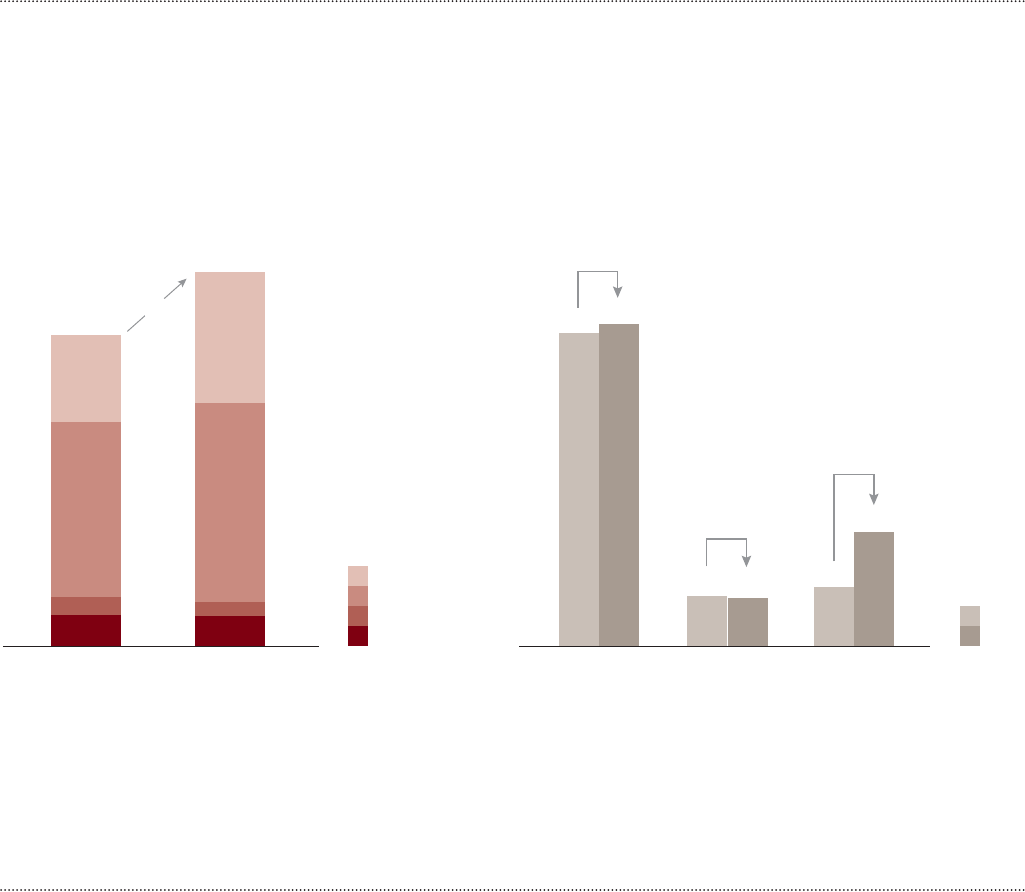

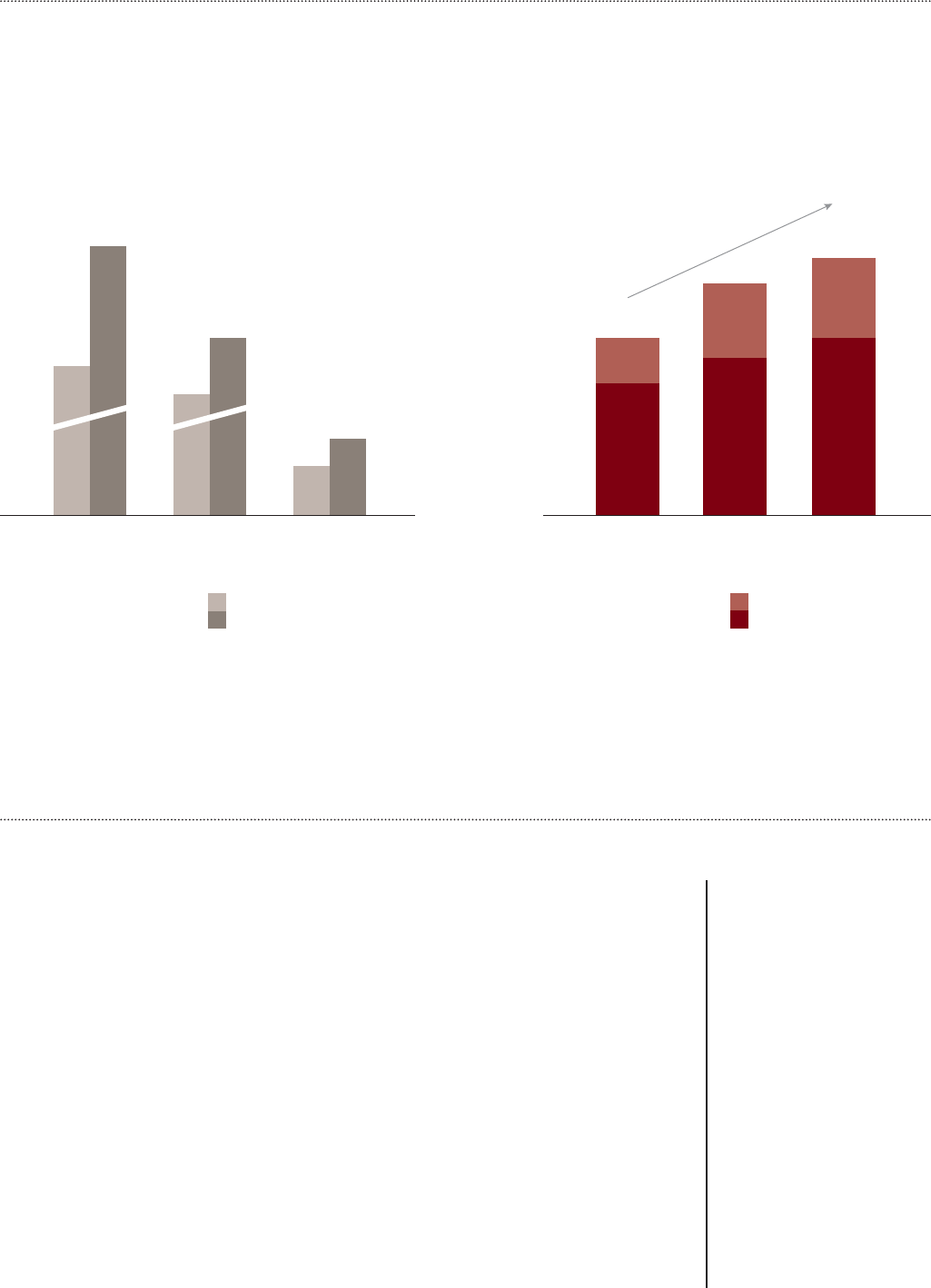

just 10 percent for traditional authors (see Exhibit 4).

Electronic gaming. The electronic gaming industry has reaped

extraordinary rewards from the Internet. Enabled by a higher-

performance broadband infrastructure, online and mobile games have

been fully embraced by the industry and across all age groups. The

emergence of new gaming platforms such as Facebook, the iTunes Store,

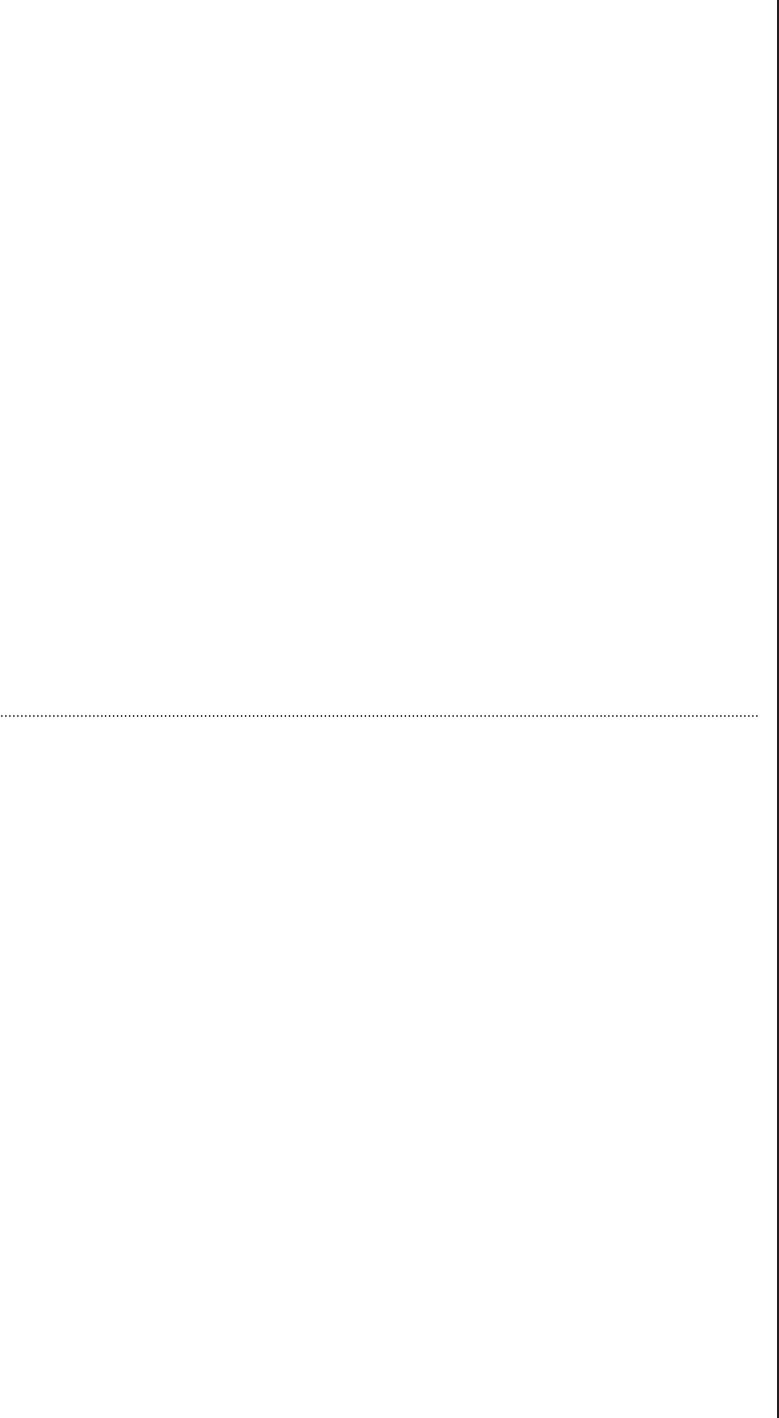

Google Play, YouTube Gaming, and many others has also reduced

Source: PwC’s Global

Entertainment and Media

Outlook; interview with

manager at TCDC; Forbes

Thailand; Strategy& analysis

Exhibit 4

Financial benefits of self-publication

70%

45%

30%

10%

15%

30%

Online book

distribution

Traditional book

distribution

Publisher

Distributio

n

Production

Author

Revenue allocation from books in Thailand

18 Strategy&

barriers to entry for game publishers, thanks to lower distribution costs

and the lower production requirements of producing social games.

The shift in platforms is also attracting new consumers who might not

have used a console but will spend time playing games online or on a

mobile device because it is convenient. In fact, although users of casual

games would not call themselves “gamers,” they end up spending more

time playing than hard-core gamers.

Globally, games have rapidly become one of the largest paid-content

categories online, thanks primarily to the growing preference for

“freemium” models, in which the basic app is oered free but additional

options are available for a price. In fact, freemium-based models,

featuring either in-app purchases or desktop-game micro-transactions,

have been growing more rapidly than the overall gaming market

everywhere. Freemium-based games grew by an average of 13 percent

per year from 2011 to 2015 in Japan, compared with 11 percent for the

total game market, and by 21 percent per year in South Korea compared

with 19 percent for the total market. Online micro-transaction and

social/casual games, which are mainly based on freemium models,

contributed 73 percent and 91 percent to Japan’s and South Korea’s

gaming revenues, respectively, in 2015.

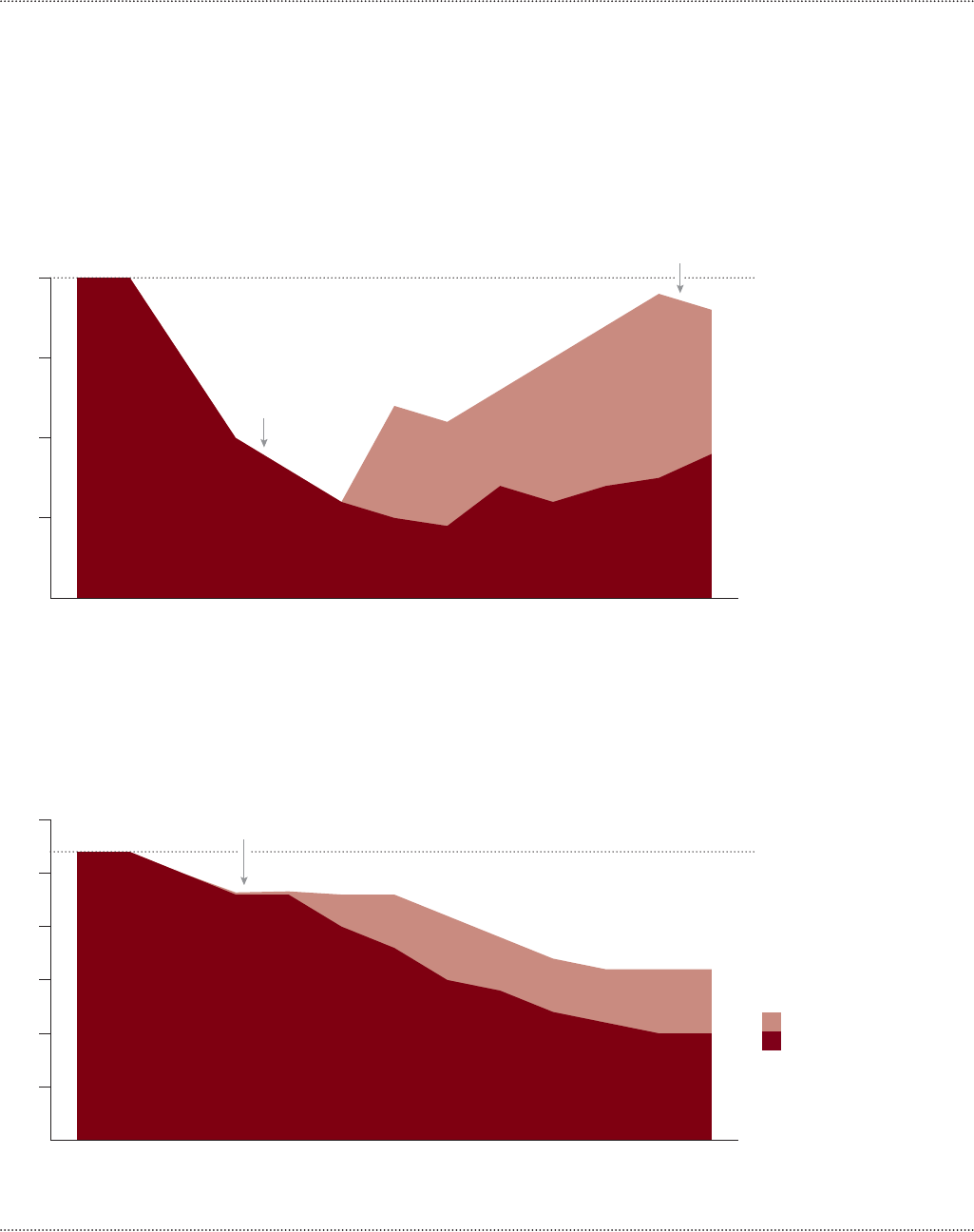

Music. The market for paid music has been experiencing a revival over

the past decade or so, thanks to live music events and the success of

legal international distribution platforms such as iTunes, Apple Music,

Spotify, Pandora, and YouTube, as well as many local players such as

MelOn and Mnet in South Korea. These companies have been able to

convert casual pirates to paying consumers through a value proposition

focused on content variety, accessibility, and flexible pricing. In turn,

this has fueled a revival in recorded music sales.

With the establishment of digital downloads as an alternative to

physical recordings, beginning with the rise of iTunes in the early

2000s, the economics of the industry fundamentally changed. Today,

about 66 percent of revenues from a download go to the artist and label,

compared with about 32 percent for a CD sale. The additional share for

artists and labels is coming almost entirely from the reduction in

intermediary and distribution costs as a result of the new formats (see

Exhibit 5, next page).

Music consumption patterns vary from country to country; in Japan and

Australia, for example, the culture of downloads is still dominant,

whereas in Thailand, Korea, and India, streaming is the preferred way

of listening. Overall, however, music is slowly shifting toward a culture

of “access,” rather than ownership, as streaming platforms become the

main source of music consumption. In Australia, for instance, the

The shift

in gaming

platforms is

attracting new

consumers who

might not have

used a console

but will play

games online

or on a mobile

device.

19Strategy&

streaming model grew 183 percent between 2014 and 2015 and

download services grew 90 percent. It is worthwhile to contrast these

countries with Norway and Sweden, which have the highest share of

streaming penetration. We expect the portion of revenue from

downloads to continue to decline over time in most countries worldwide

(see Exhibit 6, next page).

Streaming platforms provide both leading and nascent artists with ways

to distribute their music at limited cost, promotional platforms with

international reach, and direct channels of communication with their

fans. The shift from downloads to streaming has created its share of

controversy, however, as artists and songwriters raise concerns about

the amount of royalties they receive from their streamed music. What is

clear is that streaming is becoming an increasingly important source of

revenue for the music industry. For example, Australia grew digital

music revenues by more than 29 percent per annum between 2011 and

2015, adding AU$405 million (US$306 million) to the total of AU$2.7

billion.

7

Source: “The digital future of

creative Europe” (Strategy&

white paper, 2013)

Exhibit 5

Profit redistribution in the music business

14%

8%

5%

22%

19%

32%

14%

7%

13%

66%

CD sales Online download

Intermediary fe

e

Publishing

Distribution

Sales tax

Trade

Manufacturing

Artist and label

Profit distribution of physical sale vs. online download (% of sales price

)

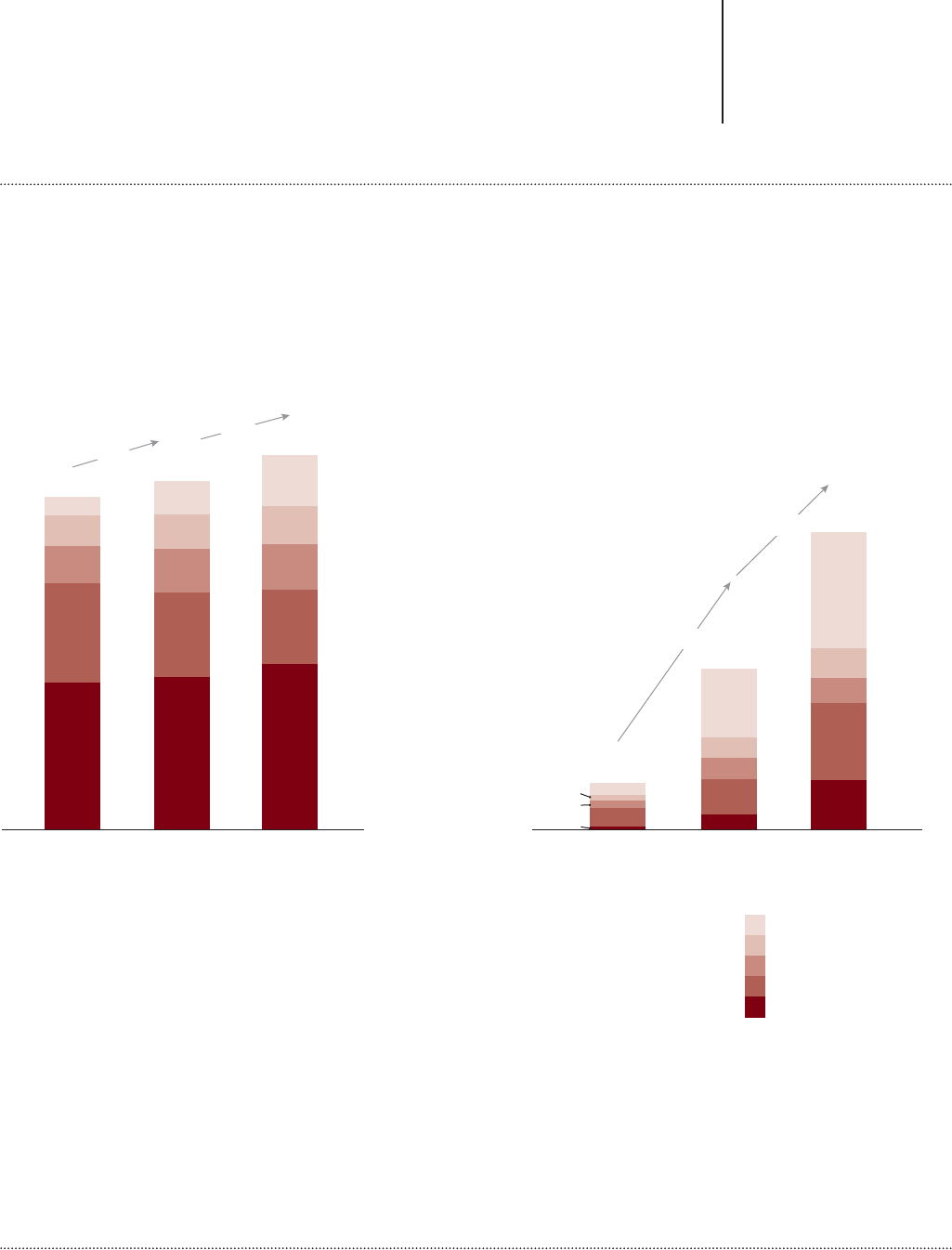

20 Strategy&

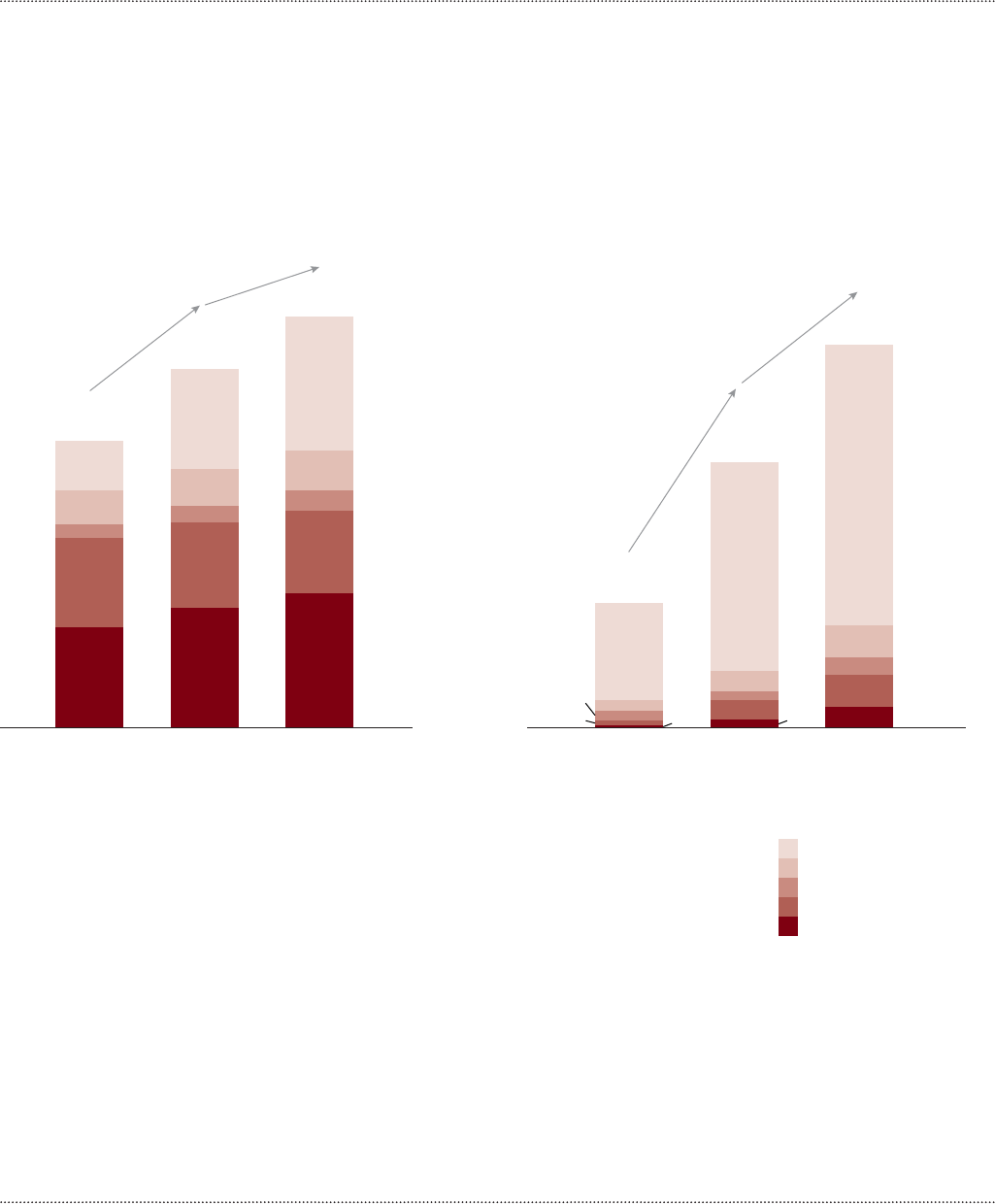

Growth in the creative industries is digital

As dierent as the countries and creative industries we studied are, six

common themes unite the overall eect of the Internet on the creative

sector and on these countries’ economies as a whole.

1. The time spent consuming creative products is increasing.

Consumer media usage is growing across every country in our study,

from those with relatively low Internet penetration to those with

penetration rates close to 100 percent. The amount of time devoted to

oine and online media consumption has increased fastest in countries

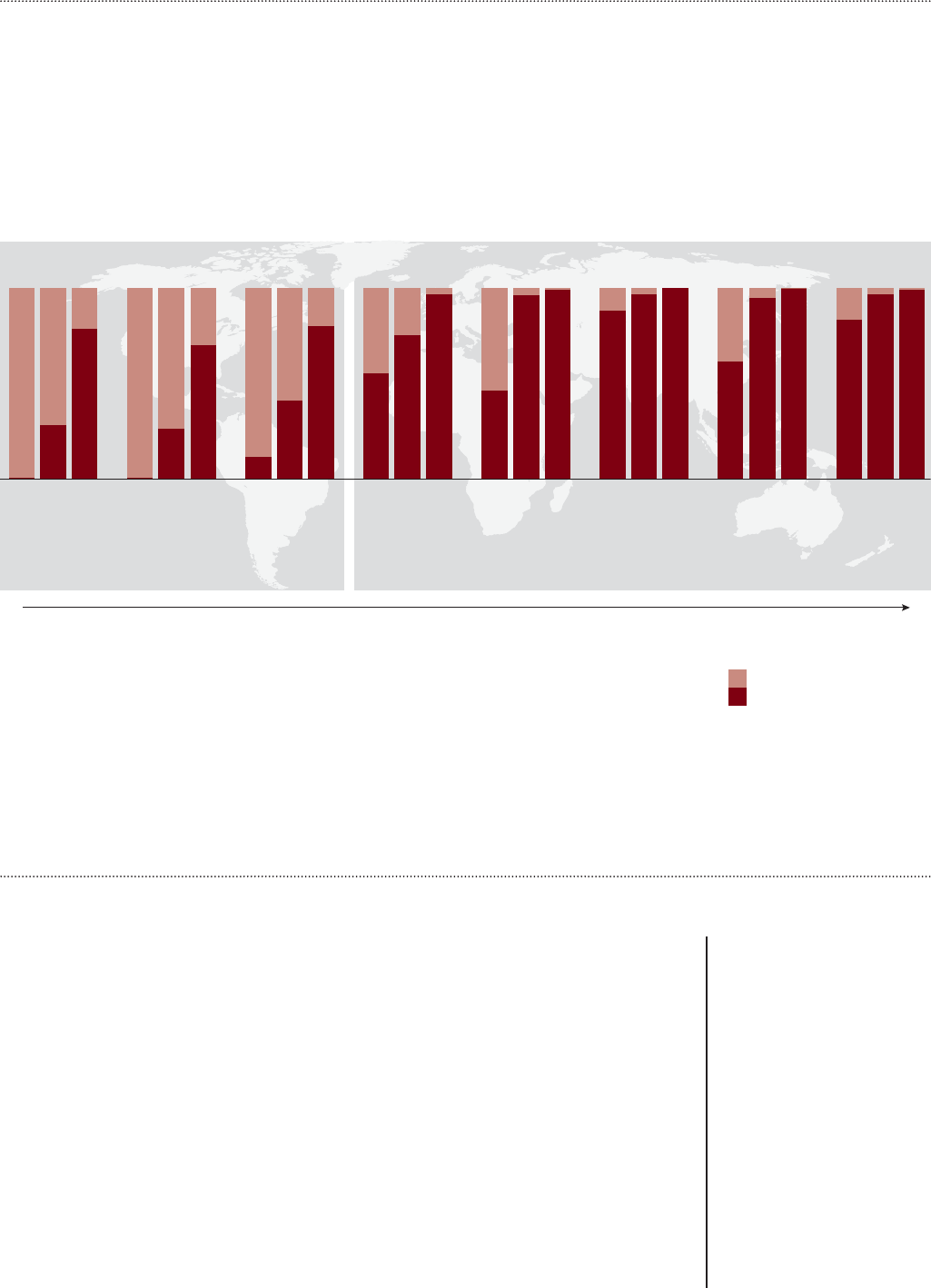

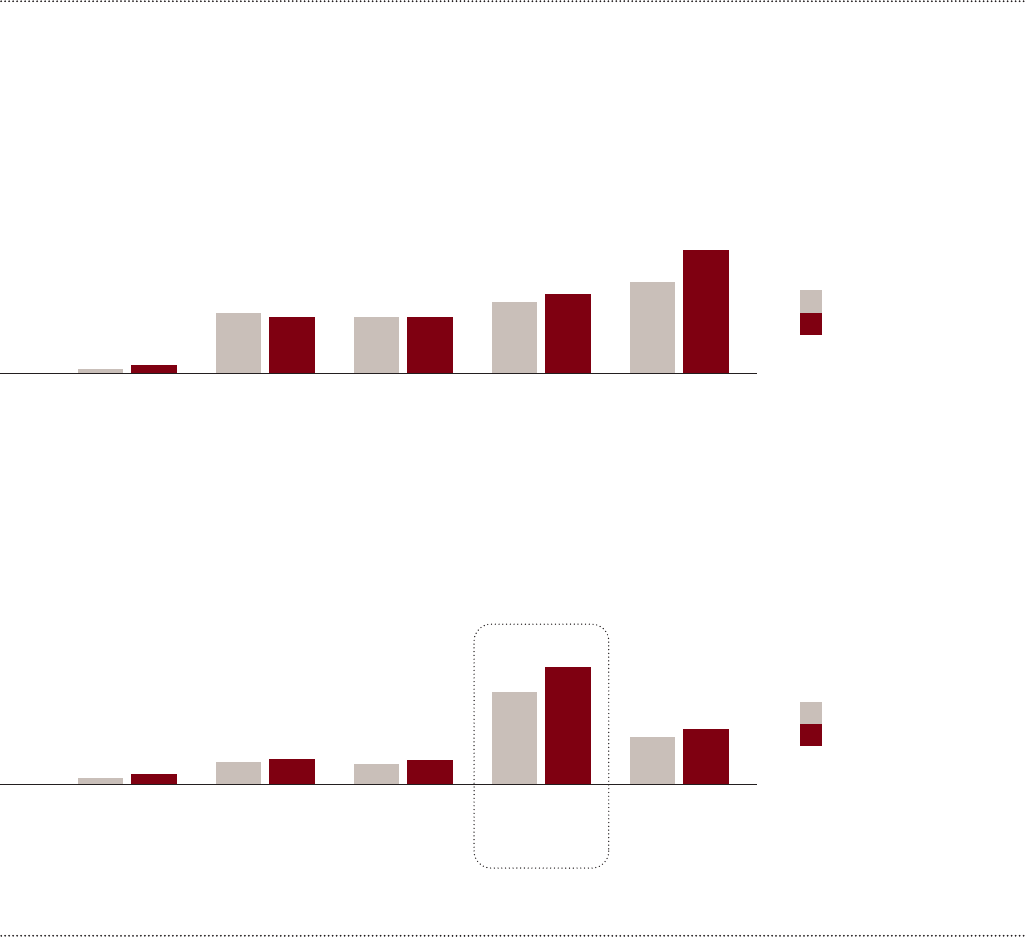

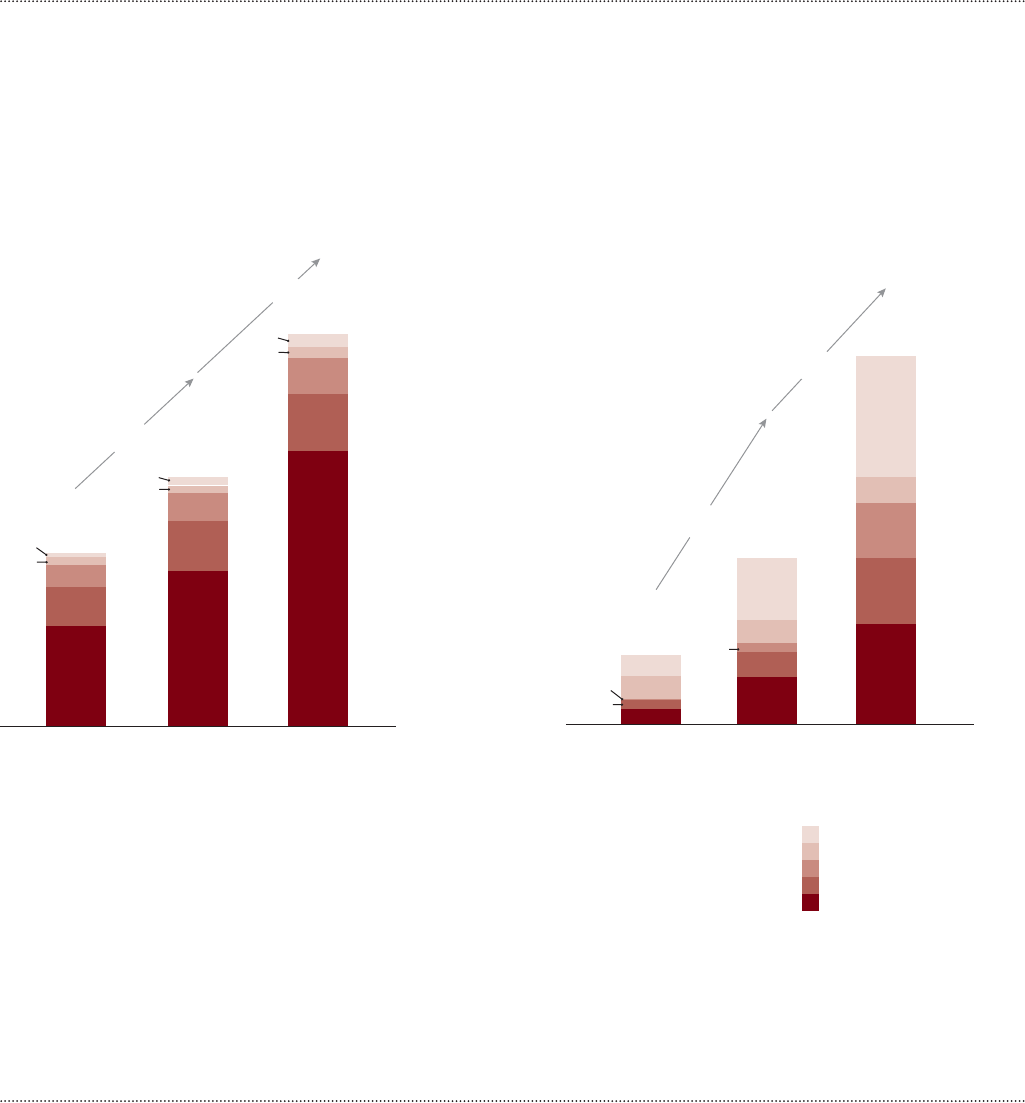

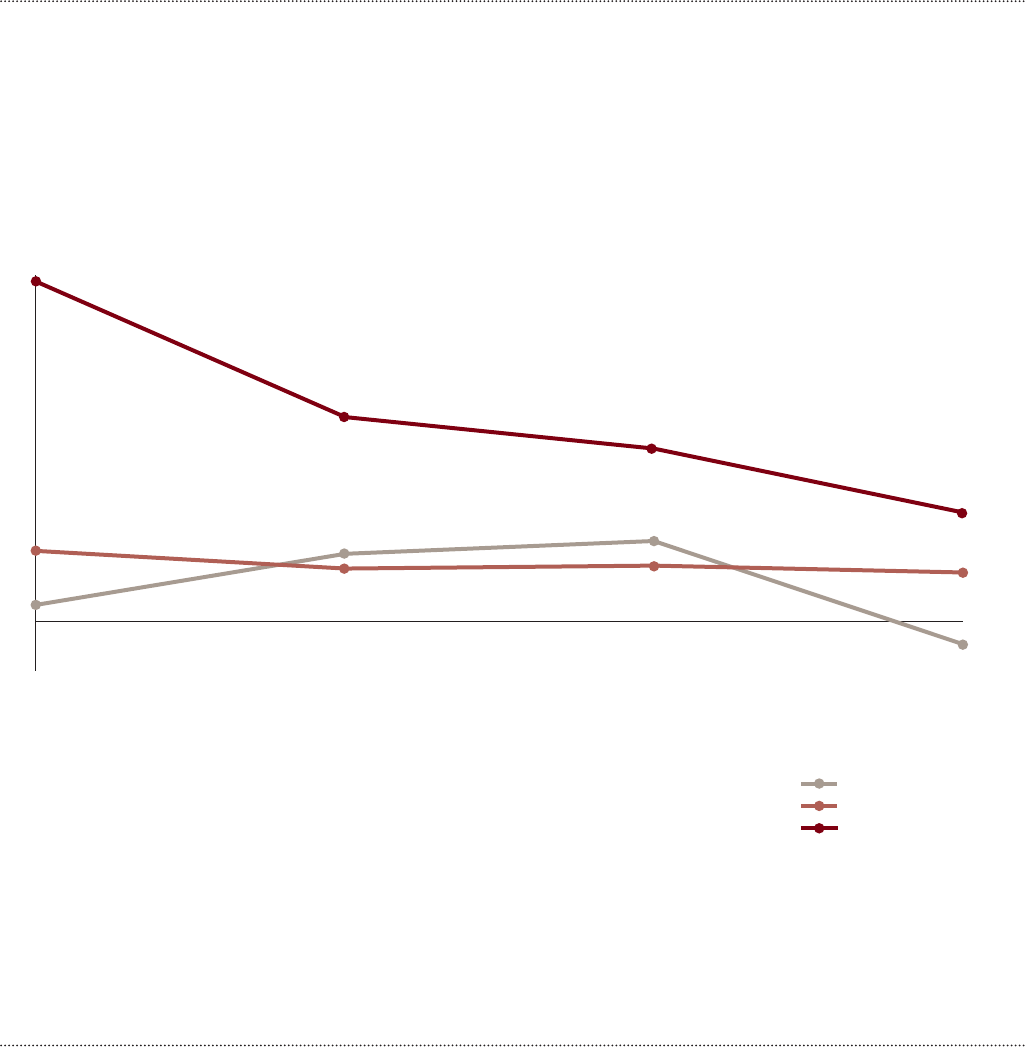

Source: PwC’s Global

Entertainment and Media

Outlook; Strategy& analysis

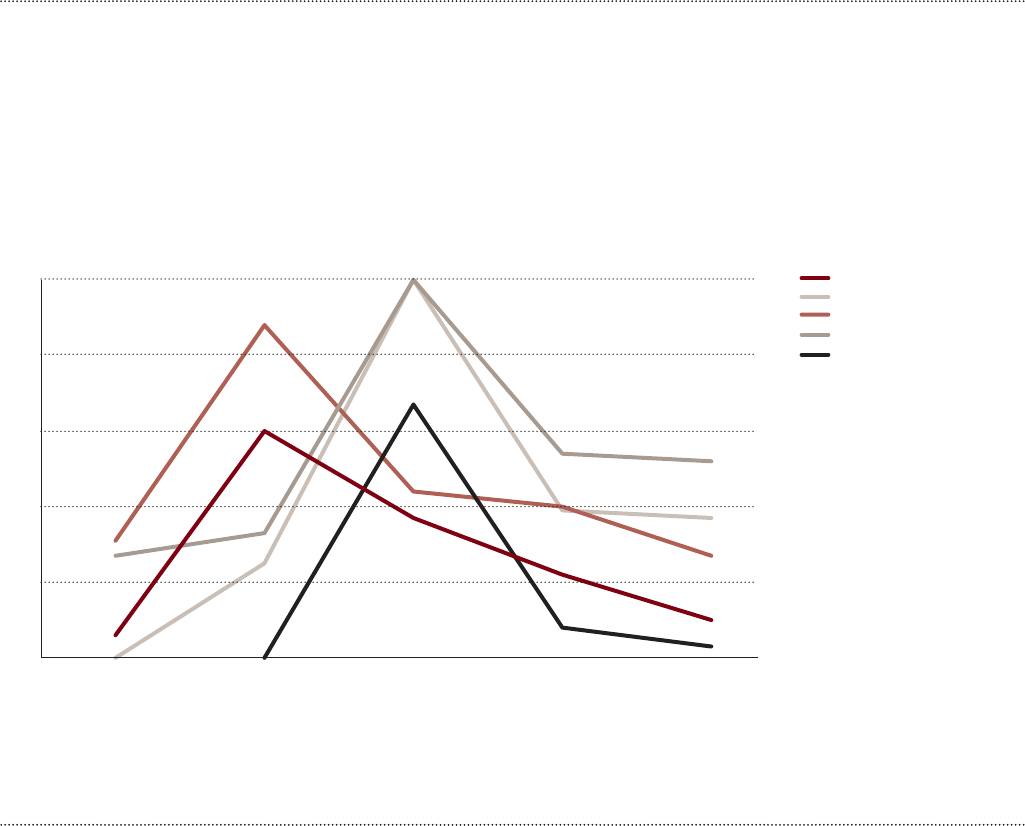

Exhibit 6

Increase in music streaming

Digital music market revenues by downloads vs. streaming

(select countries in US$ millions)

Streaming markets —

culture of access to music

Download markets —

culture of music ownership

Australia U.S.Japan Norway SwedenSouth Korea

2020F

99%

1%

2015

96%

5%

2011

61%

39%

2020F

100%

59%

2011

12%

88%

2020F

70%

17%

2020F

99%

2015

95%

2020F

99%

4%

2011

46%

54%

2020F

97%

1%

2015

97%

3%

2011

83%

30%

2015

27%

73%

2011

1%

99%

2020F

79%

21%

2015

29%

71%

2011

1%

99%

12%

2015

97%

3%

2011

88%

45%

2020F

80%

20%

2015

41%

3%

2015

75%

25%

2011

55%

General trend

Thailand India

1%

Music streaming

Music downloads

21Strategy&

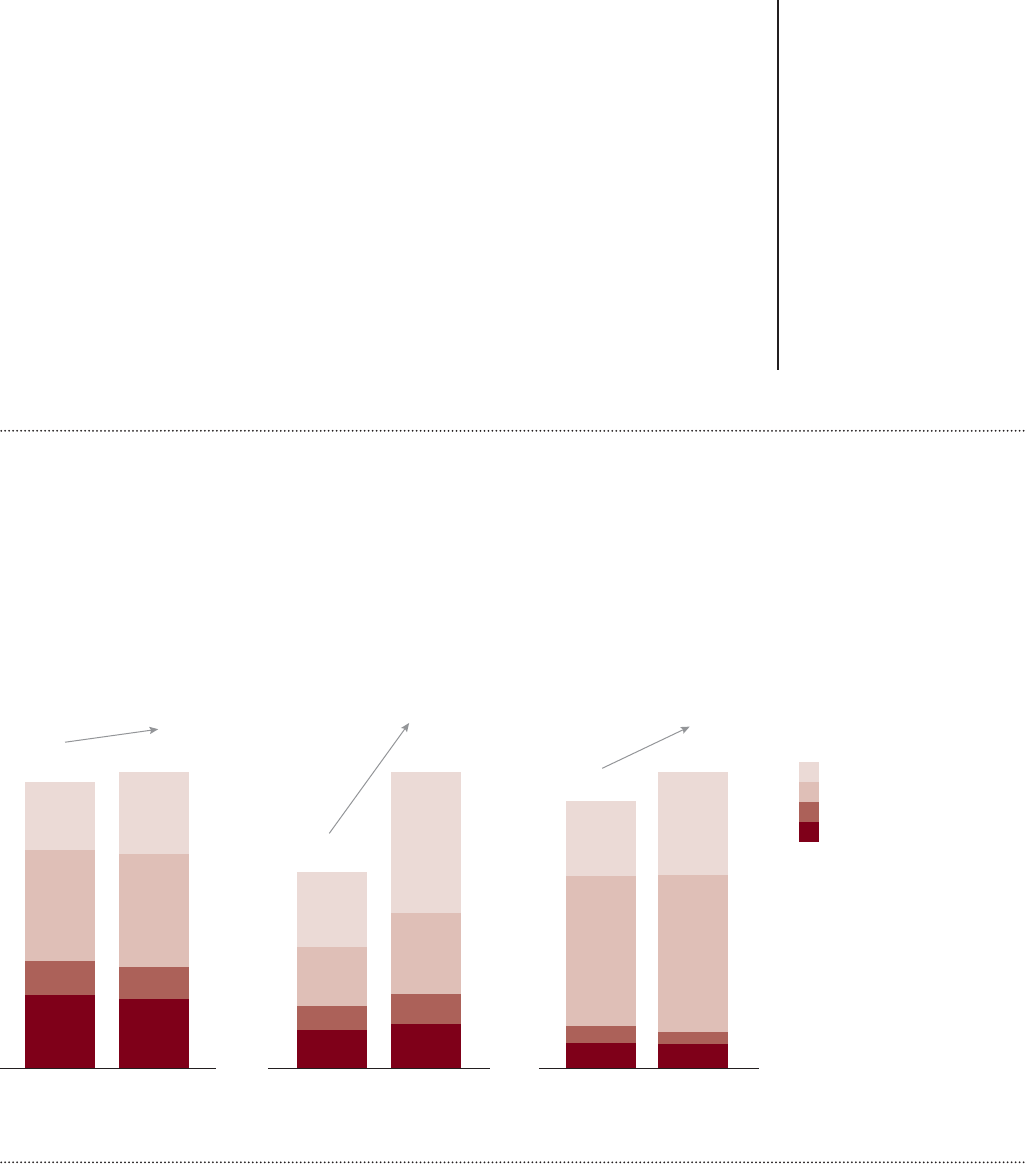

with strong Internet penetration, such as Australia and South Korea

(see Exhibit 7).

• The increase in time-consuming media is the highest in Australia,

up from 6.4 hours per day in 2011 to 9.7 hours in 2013, an annual

increase of 11 percent. That increase is occurring without

cannibalizing users’ consumption of traditional TV, radio, and print.

TV consumption increased by 13 percent from 2007 to 2013, and

consumption of print media rose 7 percent during the same period.

• Online video consumption in India doubled between 2011 and 2013,

while traditional viewing platforms such as TV and cinema

continued to grow in popularity.

Note: Results of

calculations may not be

exact due to rounding.

Source: Brand

Connections; Nielsen and

Videology 2014 report;

Statista (from GroupM);

Newswire, 2014

Exhibit 7

Increased time spent on media, by country

Print

Internet

TV

Radio

Thailand

Time spent on media

(hours per day)

23%

2010

12%

39%

9

26%

28%

11%

9

2014

38%

23%

+1%

Australia

Time spent on media

(hours per day)

30%

38%

9%

16%

6

47%

27%

2007

11%

21%

2013

10

+7%

South Korea

Time spent on media

(hours per day)

2010 2013

8%

10%

53%

5

35%

6%

4%

56%

6

28%

+4%

22 Strategy&

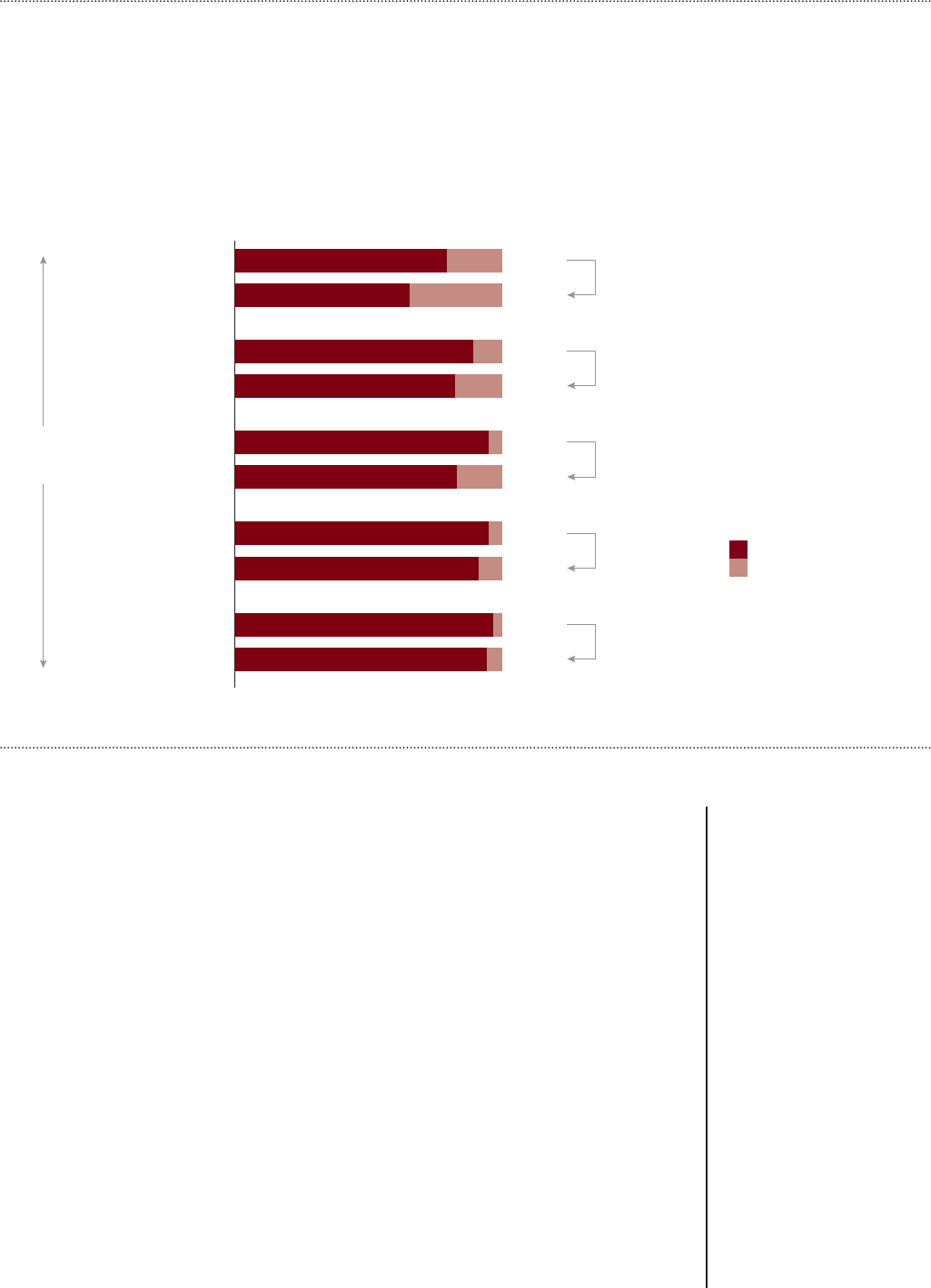

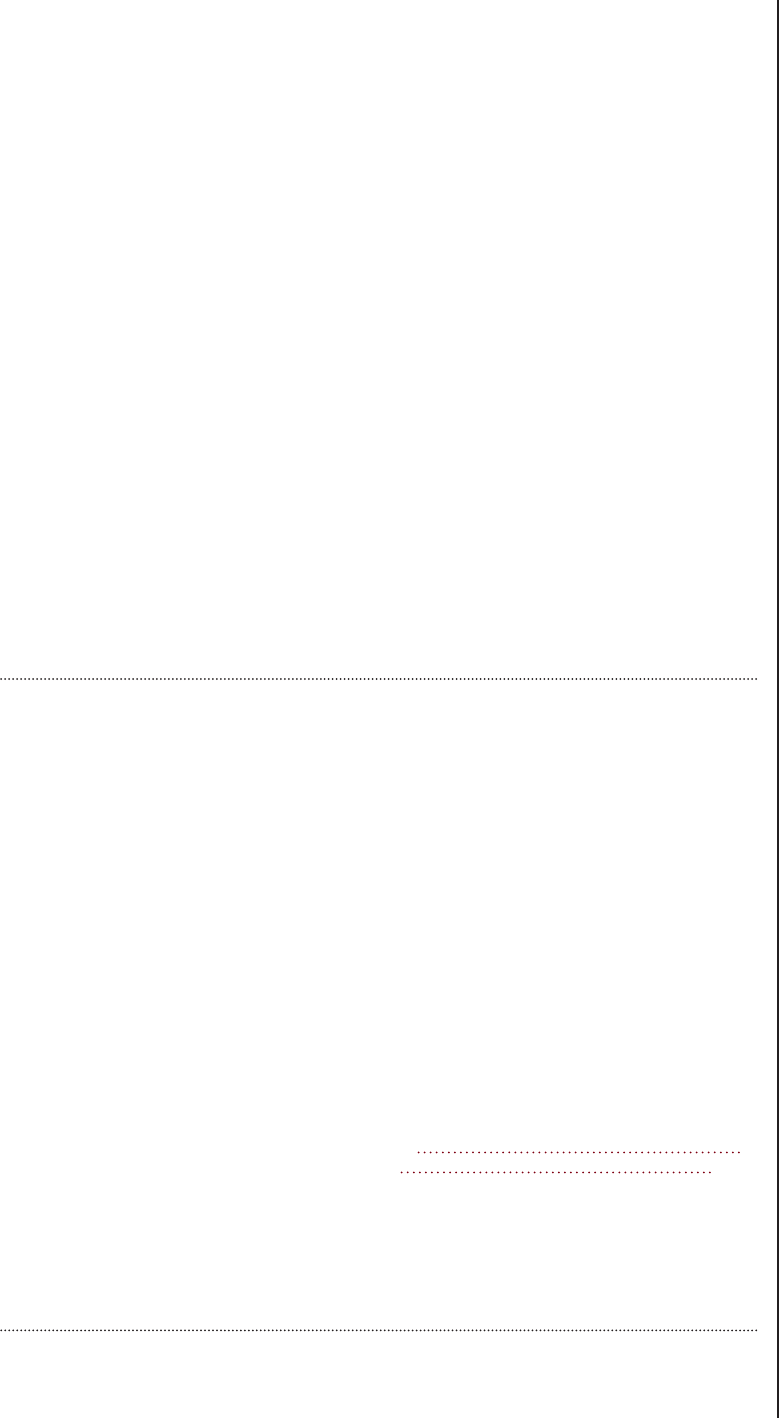

2. Users are willing to pay for creative products. Some observers

question the sustainability of the Internet as a revenue source for the

creative sector, and many believe that consumers are less willing to pay

for digital products than for their physical equivalents. Indeed, this has

proven to be a challenge for news organizations. Yet sales of digital

content show that consumers, as they spend more time online, are

willing to pay for content, especially if it provides variety, is of high

quality, is aordable, and has the convenience of anytime, anywhere,

anyhow consumption.

In every country in our study, consumers are spending more on digital

creative products than ever before— from 15 percent annual growth in

Japan between 2011 and 2015 to 35 percent annual growth in Australia

for the same period (see Exhibit 8, next page, which shows data for

Thailand, Australia, and South Korea, the markets for which we had

analogous data).

The rapid international growth of distribution platforms— such as

Netflix, a TV streaming service; Spotify and Apple Music, streamers of

music; and local players such as Hollywood HD and iFlix in Thailand—

provides strong evidence of the increased willingness to pay for digital

content.

• With a flexible pricing model and a unique content library, Netflix

attracted 1.6 million sign-ups and 900,000 paying users in Australia

less than six months after its launch there, Citi Research estimates.

8

• Digital games are large drivers of online payments, particularly in

Korea and Japan, where the Internet is driving increased per capita

gaming spend for both PC and app-based games. Game apps are

leading the surge in Japan, where expenditure per capita grew by a

total of 232 percent between 2010 and 2015, mainly driven by the

rapid adoption of smartphones and tablets.

9

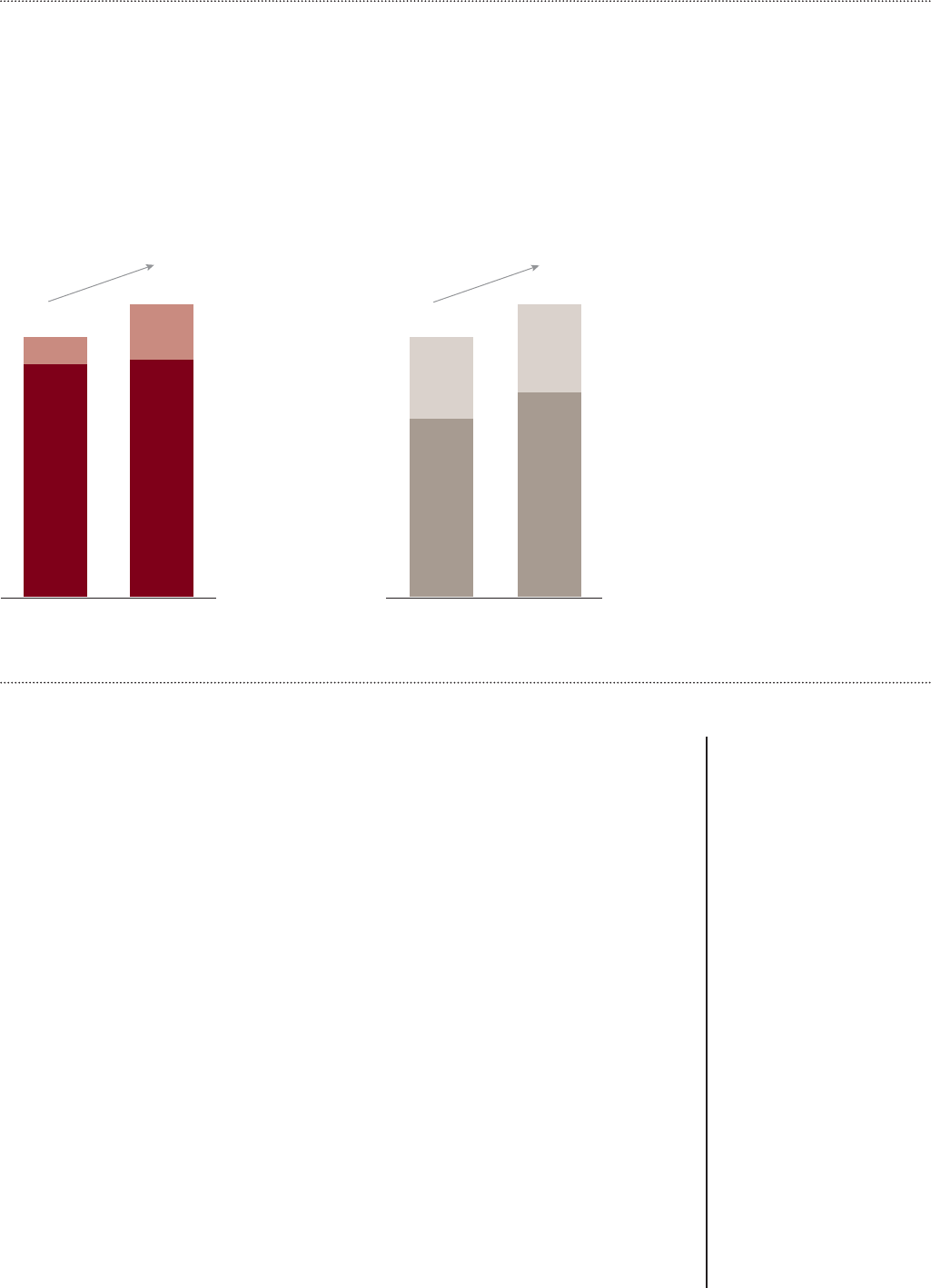

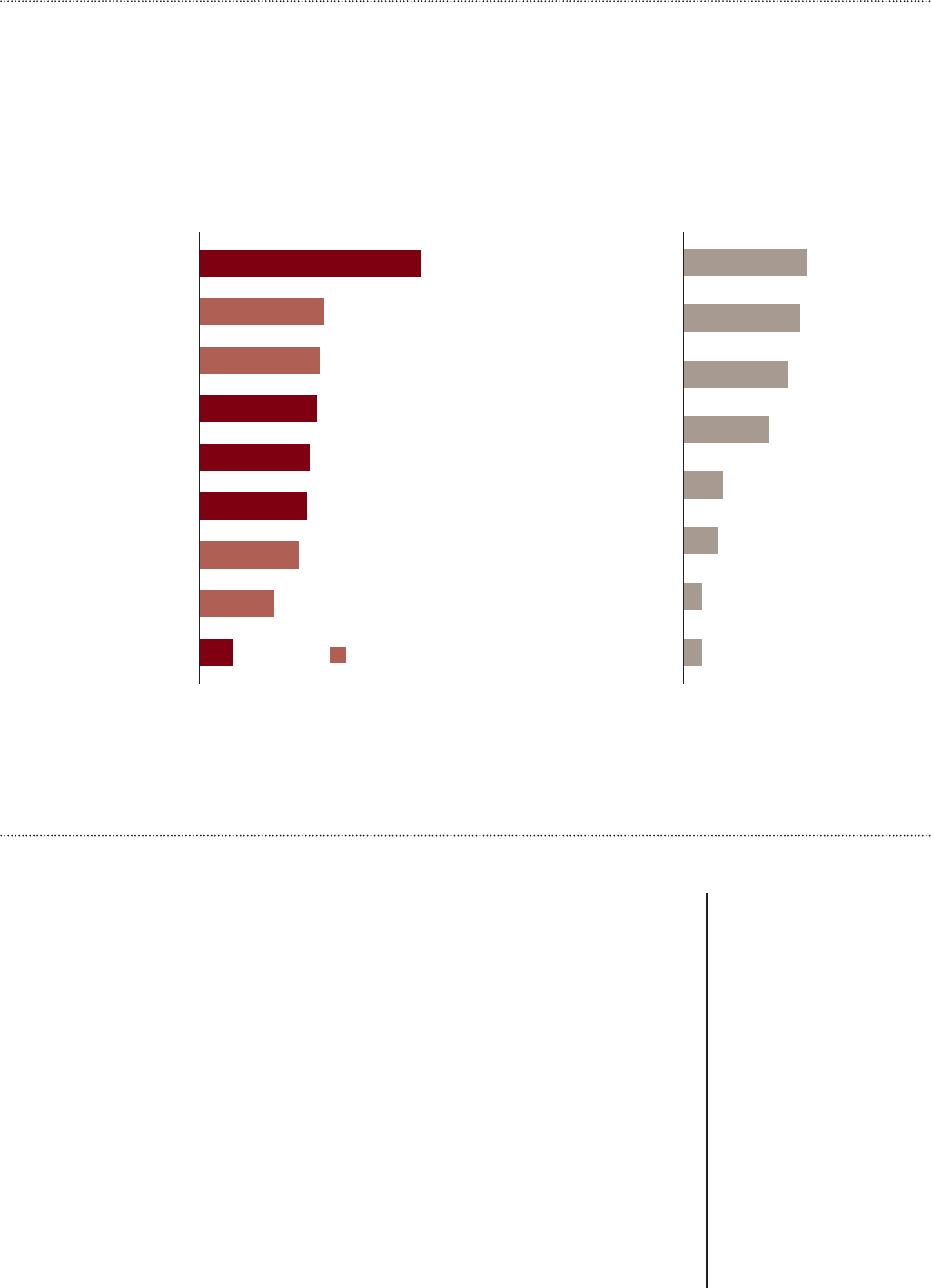

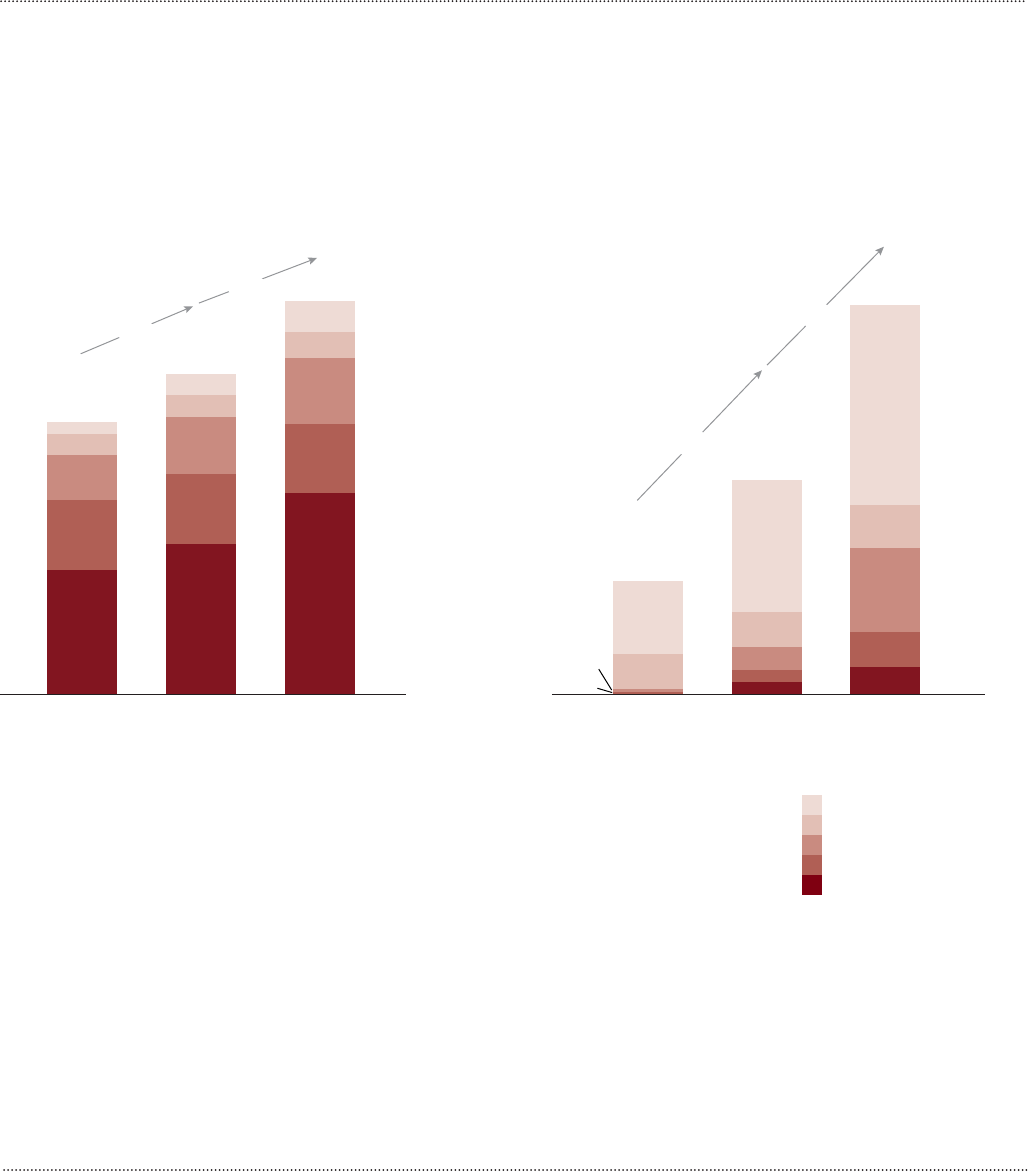

3. The overall value of the creative sector is increasing. As more

time is spent online and consumers can legally and more cost-eectively

access content, the overall value of the creative market is growing. In

South Korea, the Internet’s contribution to the total value of the creative

sector is particularly high— fully 35 percent in 2015— since digital is

increasingly part of most consumers’ DNA there. Japan’s and Australia’s

creative sectors are moderately digitized; their proportion of digital

media content is in line with that of other developed markets such as

the U.S., the U.K., and France.

Moreover, every country’s creative sector has been growing faster than

its nominal GDP, although that growth is faster in developing markets,

as developed markets become more mature. In South Korea, for

23Strategy&

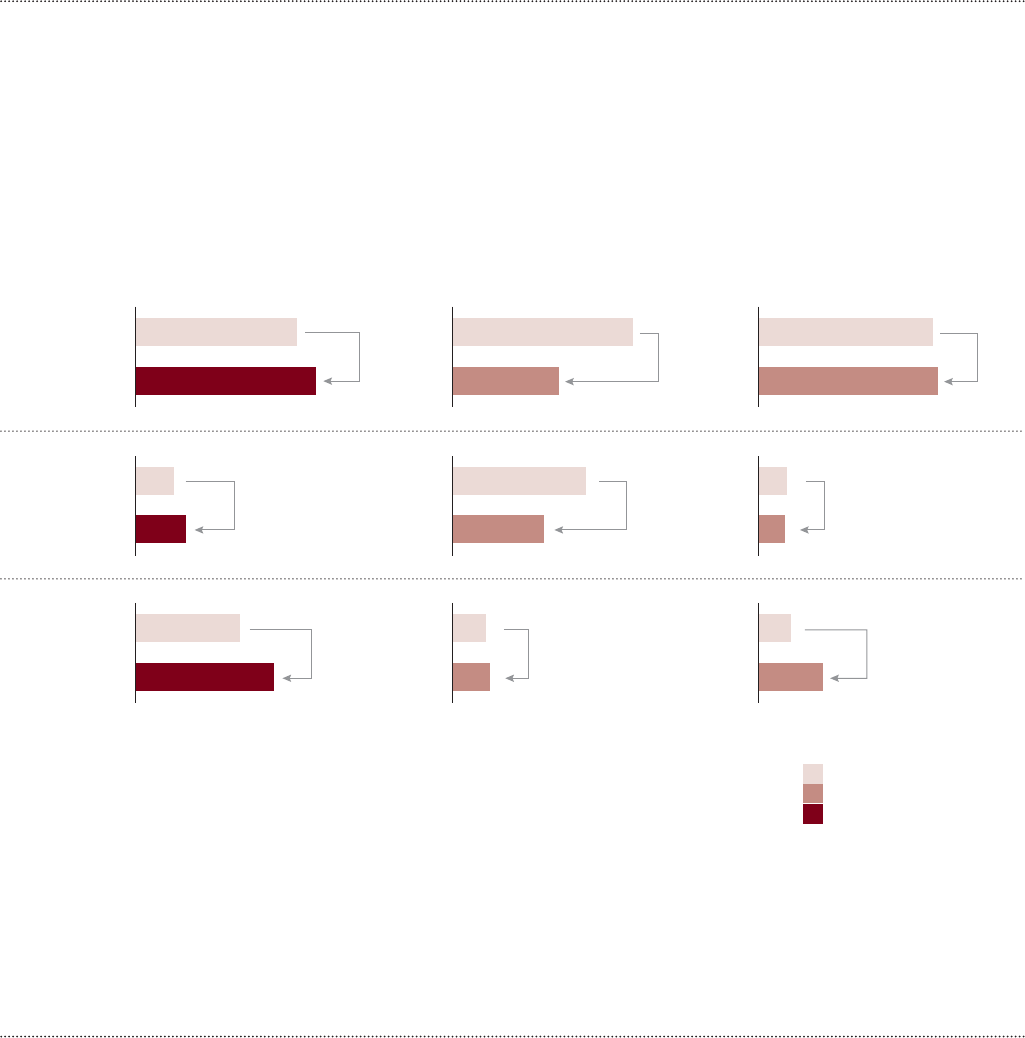

Source: PwC’s Global

Entertainment and Media

Outlook; eMarketer;

Statista; Strategy& analysis

Exhibit 8

Payments for digital content are rising

Pay monetization by hour of usage

(in US$ per 1,000 capita for print and video, and per 1,000 Internet population for digital)

Thailand Australia South Korea

Internet

$10.4

$7.9

$36.9

$32.9

$28.3

$21.4

$411.8

$244.9

$304.1

$208.3

$77.2

$85.6

$135

$262

$116

$111

$719

$737

Print

Video

+3%

2014

2013

2010

-12% +1%

+7% -9% -1%

+7% +3% +25%

24 Strategy&

instance, while GDP increased by 3 percent annually from 2011 to

2015,

10

payments for creative content increased by 6 percent and for

digital content by 21 percent for the same period

11

(see Exhibit 9,

next page).

The creation of real value, in the form of actual revenue, however, is

moving more slowly in mobile-heavy next-generation markets, since

money made from mobile channels through advertising and content

payment still lags behind revenues from larger screens such as TV and

theaters, even though consumers spend much more time consuming

content on mobile devices. Still, digital media in all five countries grew

at double-digit annual rates, with Australia, India, and South Korea

growing at 25, 24, and 21 percent, respectively, between 2011 and

2015 (see Exhibit 10, page 26).

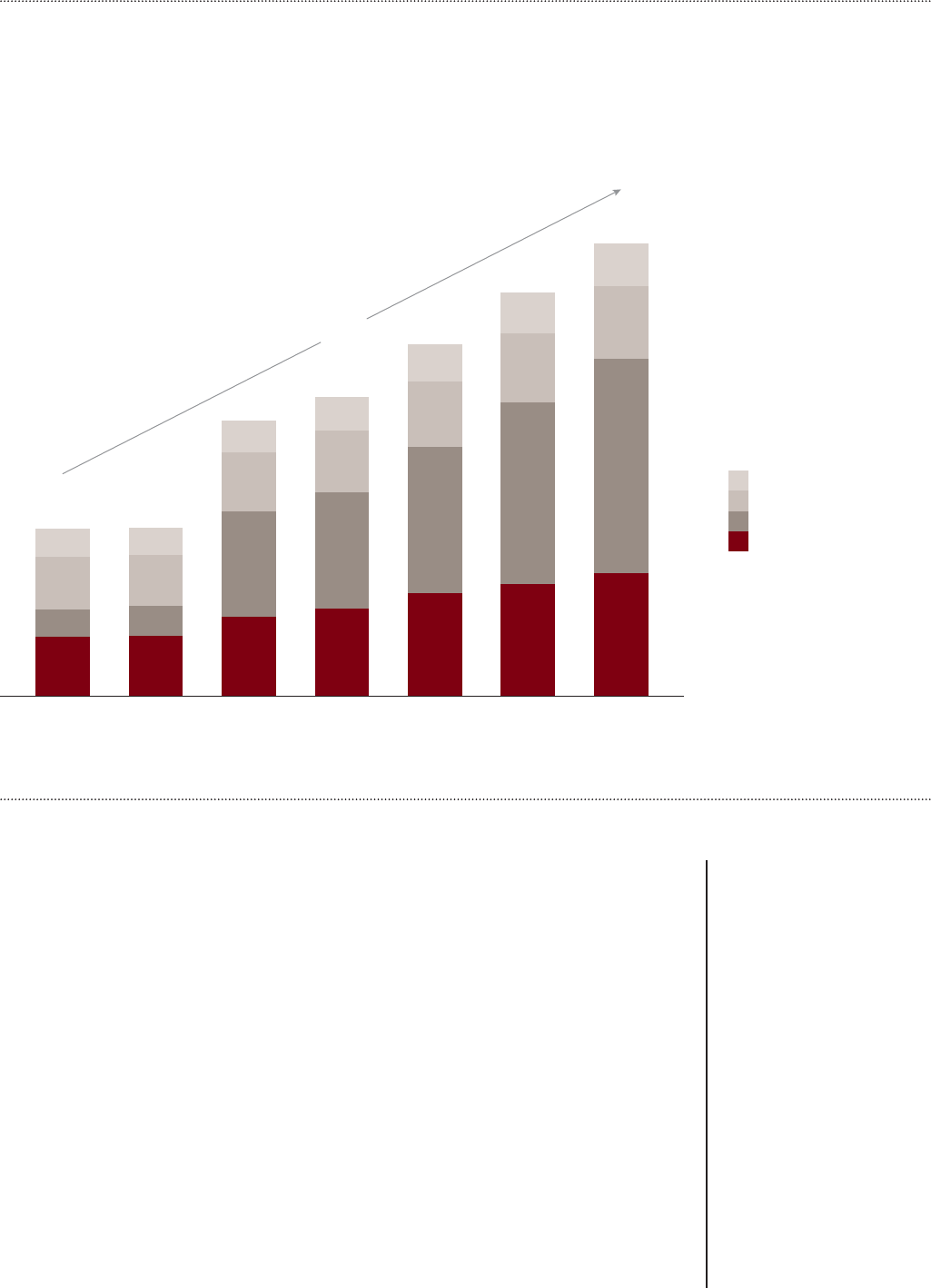

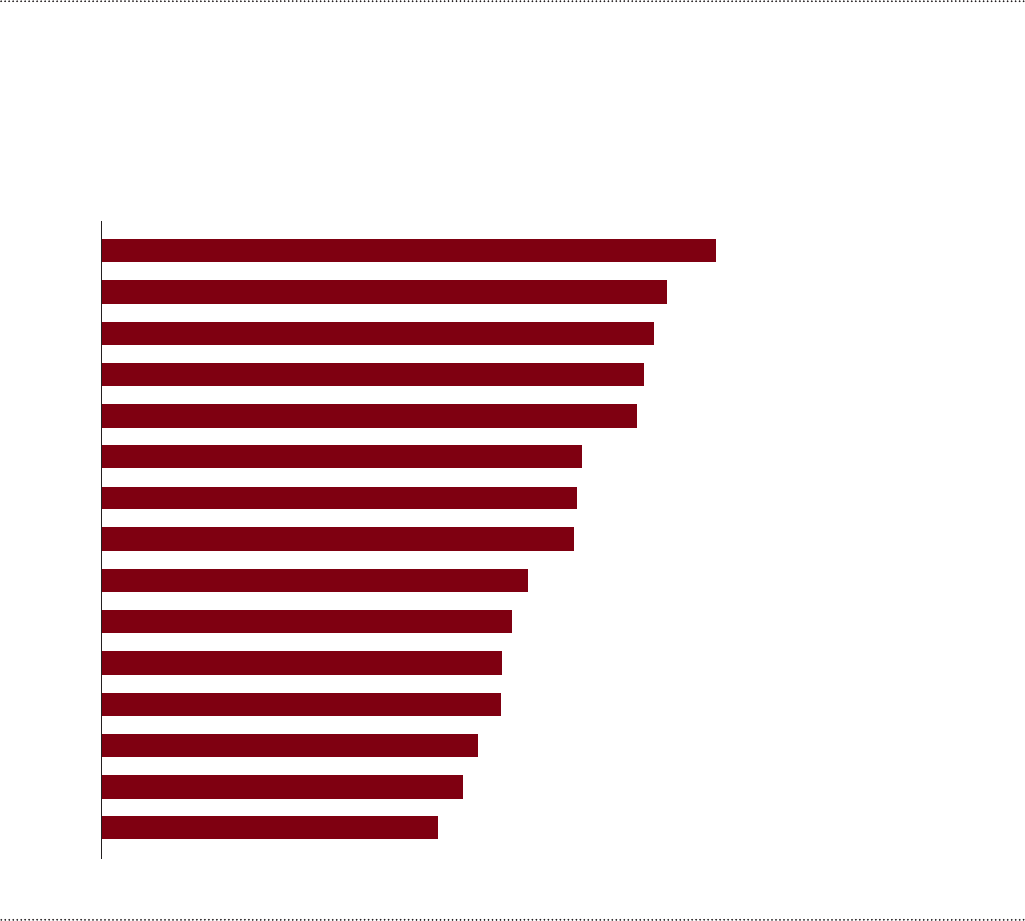

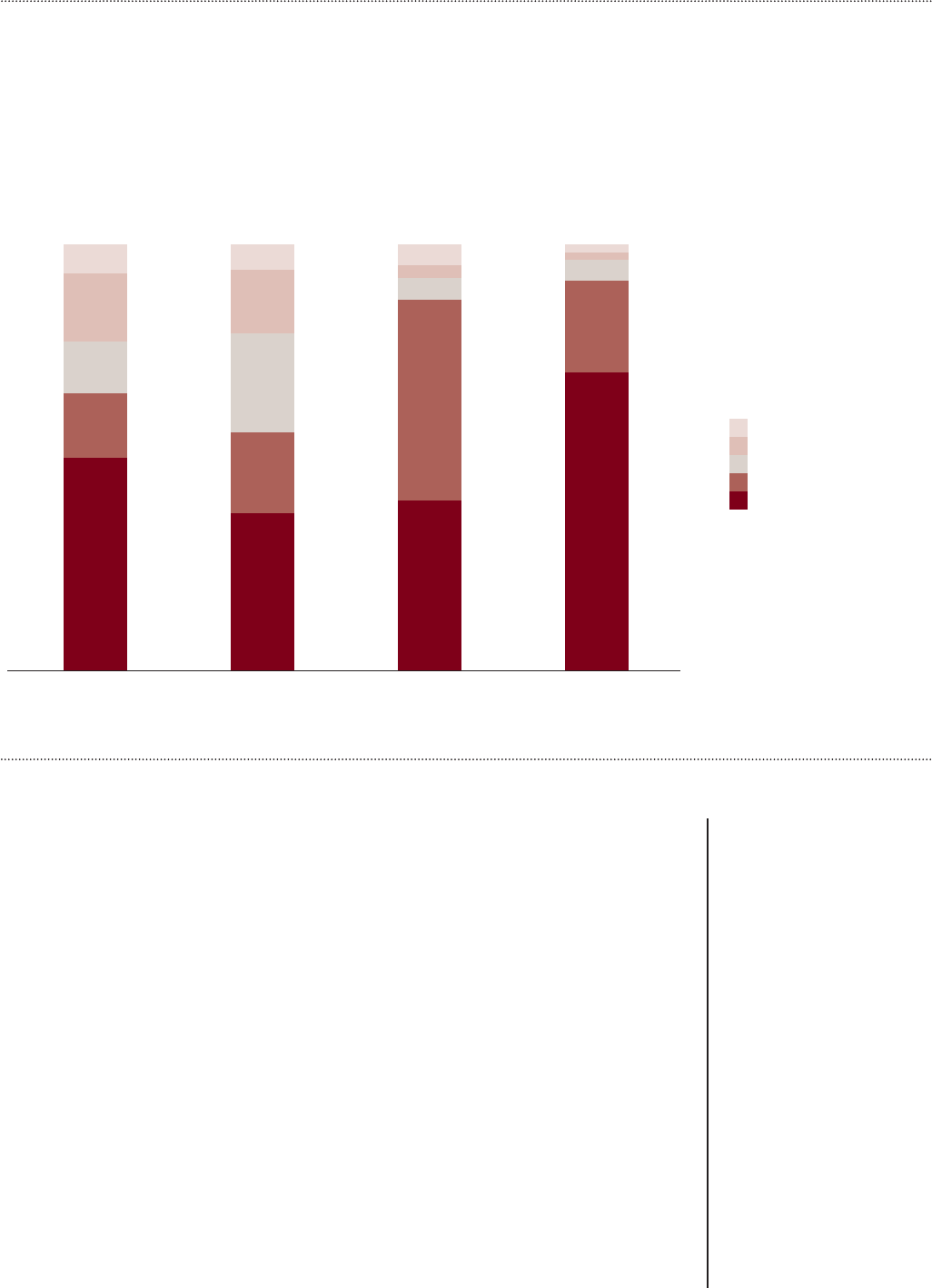

Overall, across all five countries in our study, the creative sector grew

at an average of 3 percent per year from 2011 to 2015, with most of

the growth coming from paid digital content (see Exhibit 11, page 27).

In fact, digital growth represents as much as 86 percent of the creative

market growth from 2011 to 2015, compared with 14 percent for

traditional content over the same period.

Total paid content also increased slightly faster than advertising, at 3.5

percent compared with 2 percent, for the same period, demonstrating

consumers’ increased willingness to pay for content. Paid content

growth represented 83 percent of the creative market growth from

2011 to 2015, compared with just 17 percent for advertising.

12

4. Entrepreneurship is on the rise. Traditional creative platforms

came with limited inventory space and high distribution costs, giving

the platforms’ owners most of the control and the lion’s share of the

revenue. The Internet has allowed independent artists and small and

medium-sized enterprises to build direct relationships with consumers

and get closer to the revenue stream.

The low costs of digital content production— sometimes requiring

little more than a smartphone— and the proliferation of distribution

platforms have opened up real opportunities for individual and small-

scale content creators to experiment with original oerings, showcase

their work, and instantaneously reach a critical mass of people. Indeed,

all five of the creative sector’s industries have witnessed a growth in

entrepreneurship, from video blogs, or vlogs, to indie music, microblogs,

self-published e-books, and indie games.

Individual creators also benefit from the availability of alternative

funding models and supporting mechanisms such as multichannel

networks (MCNs), which provide assistance to new video artists when it

25Strategy&

Source: PwC’s Global

Entertainment and Media

Outlook; Euromonitor;

Strategy& analysis

Exhibit 9

Growth in the creative sector compared with nominal GDP

Digital media experiencing faster growth than GDP

and still growing faster or as fast as in previous years

Digital media experiencing faster growth than GDP

with growth rate slightly decreasing as market

reaches mature levels

25

15

5

-5

20

10

0

15%

5%

15%

5%

30

40

20

0

10

-10

2013–14

21%

11%

3%

2012–132011–122010–11

35%

11%

-1%

-4%

-4%

36%

44%

41%

0

40

60

20

-20

2

%

-15

%

22

%

4%

Developing countries Developed countries

-10

%

-6

%

-17

%

1

%

1

%

17

%

12

%

16

%

13

%

10

-10

20

0

7%

2%

17%

21%

34%

11%

20

0

40

2011–12

-2

%

2014–15

5

%

8

%

2012–13 2013–14

Media market

Digital media market

GDP

Thailand

India

Australia

Japan

South Korea

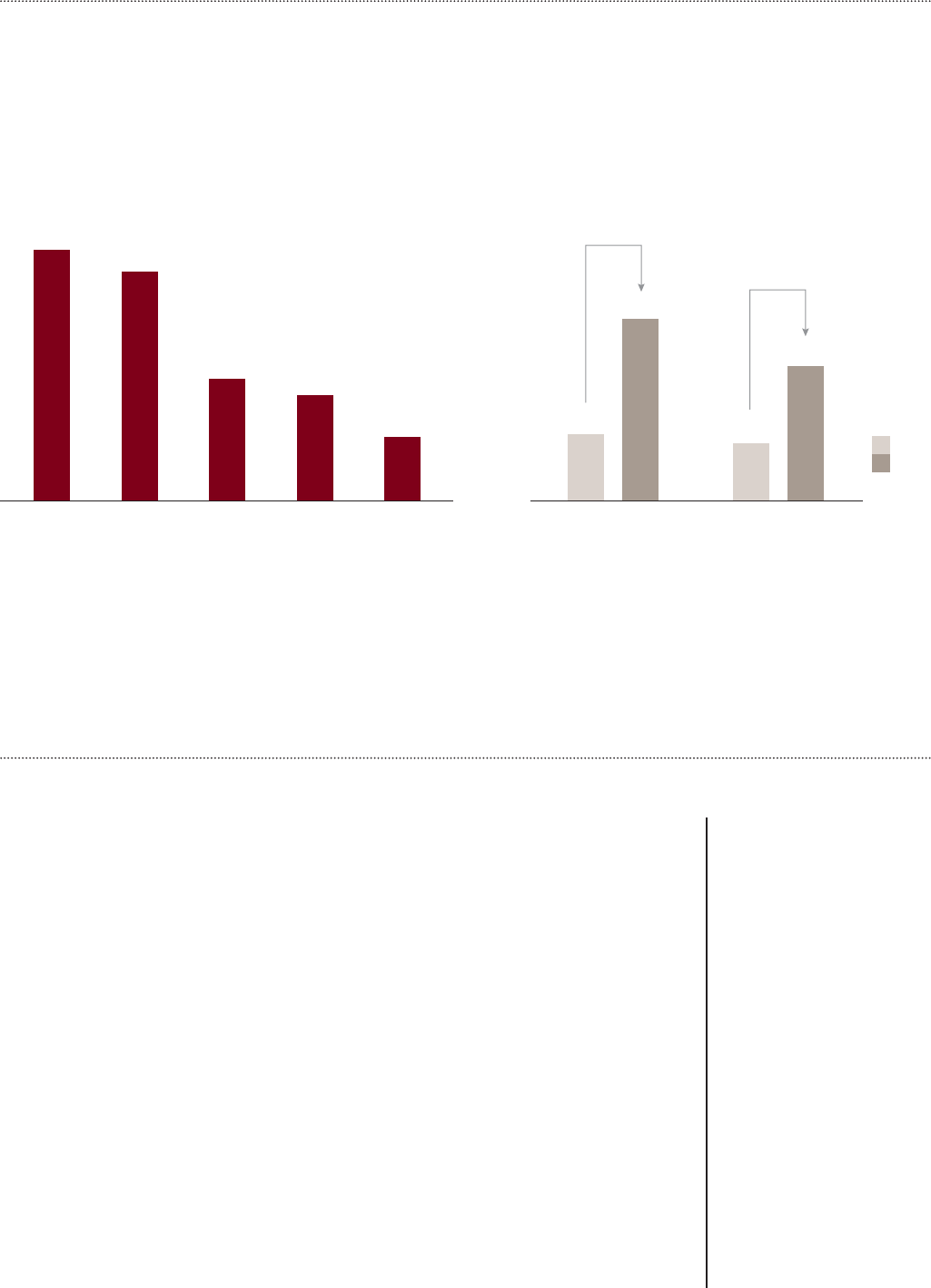

26 Strategy&

Source: PwC’s Global

Media and Entertainment

Outlook; Strategy& analysis

Exhibit 10

Digital contribution to creative sector growth

95%

83% 17%

2011

$15.9

5%

2015

$16.7

Creative

sector

digitization

15%

21%

24%

96%

94%

$13.6

4%

2015

$19.7

6%

2011

89%

82% 18%

2011

$69.9

11%

2015

$72.6

79%

65%

21%

35%

2015

$25.6

2011

$20.4

95%

91%

2015

2011

$5.6

5%

9%

$6.5

25%

17%

India

Australia

Thailand

S. Korea

Japan

Traditional

Digital

Creative sector value breakdown,

traditional vs. digital

(in US$ billions)

High

Low

Digital

content

CAGR

comes to production, distribution, monetization, and audience

development. This support helps create jobs and contribute to the

expansion of small and medium-sized businesses.

In Australia, user-generated and independent artists’ content is widely

popular; in May 2016, it made up nine of the top 10 Australian YouTube

channels, seven of which are represented by MCNs.

13

In India, in the words of the late Rajjat Barjatya, who was managing

director and CEO of Rajshri Media: “Platforms such as YouTube have

‘democratized’ the content creation process and led to the removal of

‘gatekeepers.’”

14

New entrants such as singer Shraddha Sharma now

find it easy to showcase their talent to a wide audience. Sharma’s

records had captured almost 200,000 subscribers and more than

14.4 million views by April 2016. After being discovered through

YouTube by an MCN, she signed with Universal Music and released

her first album, Raastey, in 2014.

27Strategy&

Source: PwC’s Global

Media and Entertainment

Outlook; Strategy& analysis

Exhibit 11

Growth fueled by digital and paid content

$141

81%

19%

$125

89%

11%

$141

70%

$125

69%

31%

30%

Creative sector digital vs.

non-digital breakdown

(focus countries, in US$ billions)

Creative sector ads vs.

paid content breakdown

(focus countries, in US$ billions)

Digital +18.6%

Non-digital +0.6%

Ads +2.0%

Paid content +3.5%

20152011 20152011

+3.0% CAGR +3.0% CAGR

5. Local content industries are getting stronger. A further eect of

the Internet’s ability to boost entrepreneurship and reduce barriers to

entry for independent creators is the increased supply of local content,

a significant benefit to consumers. In Australia, for example, despite

ever-expanding access to international content, trac to local sources

has risen over the past few years. In 2015, 61 percent of total trac on

the country’s top 12 sites went to local news websites, a 55 percent

increase since 2012. And according to Nielsen, the number of visitors

to “.au” websites is increasing faster than it is for “.com” websites.

15

6. Creative exports are soaring. Internet platforms have removed the

physical borders between markets and thus fueled the export of

creativity across all five creative industries. In countries where a

particular creative industry has traditionally been strong, the Internet

has enabled easier access to international markets and yielded

significant export revenues for the industry’s products.

For instance, the gaming industry in Korea took in a total of US$9.29

billion in revenues in 2015,

16

and exports accounted for a third of that,

28 Strategy&

up from a quarter just four years earlier. Mobile games have become the

key driver of the growth in exports, up 40 percent annually between

2011 and 2013.

17

Many of the new Internet-based social media stars in Australia, such as

Troye Sivan, SketchShe, and Josiah Brooks (Draw with Jazza), have

established themselves in markets across the globe. Unsurprisingly,

Australia’s cultural exports are especially popular in English-speaking

countries like the U.K., the U.S., Canada, South Africa, and New Zealand.

18

India’s HooplaKidz, an animated, Web-based children’s series, has also

reached markets around the world, eventually attracting foreign

investment. In 2015, U.S.-based MCN BroadbandTV acquired YoBoHo,

the MCN of HooplaKidz.

19

A boom for consumers

Perhaps the greatest beneficiaries of the content revolution brought

about by the Internet are consumers themselves. The Internet has given

them more entertainment avenues, more access to information, and the

ability to interact with content and its producers. As a result, consumers

spend more time on media activities than ever before. And it isn’t just

passive consumption— the Internet is enabling a whole new culture of

remixing that allows consumers to co-create content and generate their

own content. Among the benefits:

1. Increased social inclusion. The rise in digital media consumption

has significantly increased the level of social inclusion around the world,

bringing together often disparate and widely disseminated populations.

This is especially true in next-generation markets, thanks to the greater

reach and more timely sharing of content, as well as a growing number

of payment options. In these markets, a vast majority of the population

does not have access to traditional media such as newspapers, pay TV,

books, and the like. The Internet has changed the situation.

The proliferation of mobile phones has fast-tracked this phenomenon,

especially in remote rural areas, where creative, informational, and

educational content is increasingly available to communities with limited

access to traditional distribution platforms such as cable and pay TV.

• Thanks largely to the proliferation of mobile devices, more than

73 percent of rural connected users in India use the Internet for

entertainment.

20

• Content providers are designing new forms of distribution for

consumers with bandwidth limitations, including content-light

Consumers

spend more

time on media

activities than

ever before.

29

versions and oine viewing. India’s Shemaroo, T-Series, Saregama,

and Yash Raj Films, for example, are oered through YouTube’s

oine feature that is available on Android and iOS platforms.

• And Hotstar, a mobile app, allows videos to be downloaded for oine

viewing; downloads of the app drove its popularity rank in India

from number 339 to 38 just between January and May 2016, and it

reached a peak as the most downloaded app on March 31, 2016.

21

2. Mobility brings greater flexibility. The Internet provides consumers

with the ability to access creative content anywhere, anytime, anyhow.

This level of mobility and flexibility is becoming the norm in both

developing and mature countries, although mobile usage is particularly

high in developing markets, which have come to depend on more

cheaply built-out wireless infrastructure.

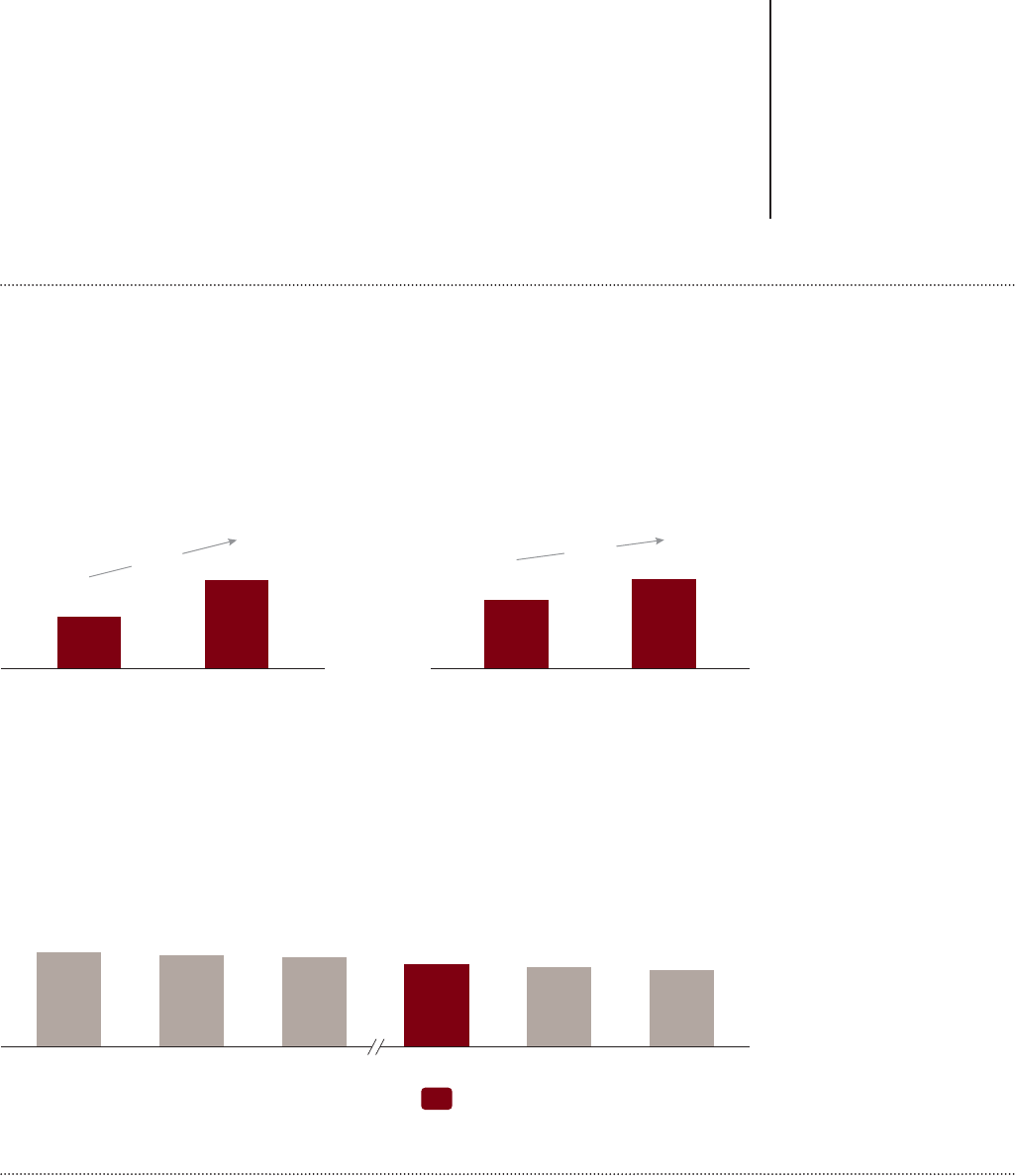

South Korea is particularly advanced in this regard. Consumers there

can access games through multiple devices, physical and mobile, while

mobility allows users to play music anywhere, anytime (see Exhibit 12,

next page).

Consumption of music and games on mobile devices in Korea more than

doubled between 2013 and 2014. In Thailand, dual-screening— watching

traditional and online TV at the same time— is particularly high; in 2015,

40 percent of TV consumption took place on dual screens, and that is

expected to reach 50 percent by 2020.

22

By 2014, the percentage of Thai

Internet users consuming online and traditional TV simultaneously had

reached 94 percent, with 76 percent doing so on a daily basis.

23

3. More choice. Consumers also benefit from a wide and increasing

variety of online content: Content archives are readily accessible,

content is updated instantaneously, and innovative niche and indie

oerings are on the rise. Major distribution platforms such as Netflix,

Hollywood HD, and iFlix oer an enormous menu of top TV shows and

movies as well as original content at aordable prices, while further

benefiting the sector by helping reduce the extent of casual piracy.

Niche players can enter the content market more easily, providing

previously unavailable content such as independent movies, indie music

genres, and self-published books of all kinds. Audiences also have access

to a large supply of local content, thanks in part to the emergence of local

independent artists in every genre. And audiences can gain access to the

archives of libraries and universities, as well as the content majors.

4. Increased user participation. The Internet has enabled consumers

to engage with content in a variety of ways, from ratings to uploading

videos to commenting on articles. The Internet also lets audiences form

their own communities of interest and interact more directly with

30 Strategy&

Source: “Mobile Gaming

Cross-Market Analysis”

(InMobi report, 2014);

TNS Infratest; Statista;

Strategy& analysis

Exhibit 12

Mobile usage in South Korea

Koreans’ time spent on mobile game play

(% respondents, 2014)

Music and game usage on smartphones in Korea

(% respondents, 2013–14)

47%

43%

23%

20%

12%

While

watching TV

At work/

school

While

commuting

At

home

While

waiting

Games

Music

58%

21%

18%

43%

2014

2013

+176%

+139%

artists and public figures in the news. Consumers are fast becoming

actors in the very content they consume, through online communities,

video sharing, and citizen journalism sites such as Internet giants

Facebook and YouTube as well as local players such as Kakao in South

Korea, Line in Japan, and Pantip in Thailand.

Opportunities for content majors

The community of traditional content creators— including traditional

film and TV production groups, broadcasters, record labels, and

newspaper and book publishers, among others— used to control a

large part of the content value chain, integrating the creation,

production, and distribution processes. They also aggregated content

and commissioned a large portion of the output of content creators.

Now, however, they are feeling the impact of the new forms of creation

31

and distribution enabled by the Internet, which has pushed them to

adapt by creating new business models.

New technologies are being broadly used by most of the content majors.

The Internet has revolutionized the way creators work and collaborate.

This trend is true for most markets, including the next-generation

markets. Even data-heavy film production in Bollywood is now being

put online, allowing collaborators from around the globe to access the

same video material in real time.

The Internet has also benefited these content majors in five key ways:

by giving them broader reach and a greater understanding of their

audiences (allowing them to find ways to sell content more eectively);

by facilitating closer relationships with audiences; by providing easier

access to talent; by opening up international markets; and by opening

up significant new revenue streams.

1. Greater audience reach and insights. By expanding their content

to digital platforms such as websites, online videos, and mobile apps,

and by distributing their content on third-party platforms, the content

majors have significantly increased their reach. In Australia,

newspapers have seen revenue from traditional sources, such as print

advertising, decline as a result of online advertising, and digital

revenues do not always make up for those losses. At the same time,

however, the absolute number of subscribers to content is growing,

thanks almost entirely to digital platforms. While the Australian print

newspaper audience decreased by 10 percent from 2013 to 2015, the

incremental audience online and on mobile devices increased by a total

of 50 percent during the same period, contributing to a net increase in

newspaper audiences of 7 percent.

24

TV broadcasters have also increased their audiences, primarily through

online video oerings. In South Korea, for example, TV broadcaster

MBC generated incremental revenues of $41.9 million in 2012 and

$46.8 million in 2014 from its online streaming oerings, and increased

its YouTube subscribers from 500,000 in 2013 to 4.4 million in April

2016, leading to additional incremental revenues.

25

2. Closer relations with audiences. While traditional media players in

such industries as television, newspapers, and music are accustomed to

managing the content value chain from creation and production to

distribution, the digitization of content has brought any number of

specialized players across every step of the value chain, especially in

creation and distribution. Now, however, a new, fully digitized

ecosystem architecture is on the rise, presenting great opportunities for

the traditional content majors as well. At the heart of the most

successful business models is the creation of a seamless consumer

32 Strategy&

experience and the development of a deeper understanding of, and

closer relationship with, audiences through online tools.

Thailand’s TrueVisions, a cable TV operator, for example, has been a

pioneer in integrating TV and social media, engaging with viewers on

social networks and adapting its content accordingly. Said Birathon

Kasemsri, the chief commercial ocer at TrueVisions: “Engaging with

TV audiences is better and easier with the Internet,” and “combining

event data with our audience’s habits and preferences [allows us to

significantly improve] targeting content and advertisements.”

26

3. Easier access to talent. In the past, the content majors spent

considerable amounts of time and money finding and grooming new

artists. Now, digital distribution platforms have given them much better

and more ecient access to new talent. As noted above, Universal Music

identified the young Indian Shraddha Sharma through YouTube and

signed her for her first album, Raastey. Sharma now finds it easy to

showcase her talent to a wide audience. Her records had captured

almost 198,000 subscribers and more than 14.4 million views by

April 2016.

Similarly, South Korea’s Applegirl rose to fame through her uploaded

YouTube videos, which feature her singing and playing songs by Lady

Gaga and Beyoncé. Her videos gained much interest— her Lady Gaga

video alone garnered 5.3 million views by May 2016— and facilitated

her signing with Dream High Music Entertainment as a singer and

songwriter.

4. International reach. The Internet has opened up important new

markets that leading content majors can tap into, benefiting the entire

creative sector. The independent Australian film industry, for instance,

has gained international exposure through such platforms as

Beamafilm. A promoter and distributor of independent Australian

movies, Beamafilm reaches audiences across Australia and New Zealand

as well as in the U.K., the U.S., France, Germany, and Mexico.

27

5. Greater eciencies and revenue streams. Content majors are

already benefiting from the generation of new revenue streams such as

the monetization of their digital content, the scaling of their oerings to

international markets, and the online distribution of older “long tail”

content that was not previously available digitally. Moreover, thanks to

large reductions in the cost of production, manufacturing, distribution,

and warehousing, the Internet allows content majors to operate much

more eciently. And the increased insight into their audiences helps

content majors to optimize their content costs to extract the highest

value from customers.

33

Many publishing companies have already shown that digital content

can be eectively monetized through new value propositions. Marina

Go, former general manager of Hearst-Bauer in Australia, notes, “The

Internet enables blue-sky thinking. It has unlocked a whole new world

of creativity for publishers.”

28

The company’s most popular magazine,

Cosmopolitan, has doubled its online audience since the mid-1990s,

from 1 million to more than 2 million, and now reaches a new digital

audience, many of whom are in their 20s, compared with the mid-30s

for the title’s print readership. Even as circulation and advertising

revenues decline, the company is leveraging the Internet to learn more

about its subscribers while also exploring new revenue streams such as

events and licensing.

Emerging artists: Unlimited value in a new digital ecosystem

By building a larger pipeline of creative material developed by

consumers, the Internet has created broader communities of creative

involvement, and opened up opportunities for emerging artists. These

artists benefit from open platforms, better access to funding, the ability

to reach international audiences cost-eectively, and increased support

from sources such as MCNs, which help promote artists on sites like

YouTube. Among the benefits:

1. Access to audiences. Thanks to a wide range of digital distribution

platforms and aordable technologies, new artists can reach consumers

directly by complementing or circumventing intermediaries and

gatekeepers. South Korea’s Sungha Jung, a previously unknown guitar

player, now has 4.2 million subscribers to his YouTube channel.

29

In 2009, Thailand’s Kirakorn Chimkool developed the Unblock Me app

game using a Mac Mini bought with a 10-month installment loan. Within

a few days of its release, the free version of Unblock Me became the 60th

most downloaded game in the U.S. App Store and the most downloaded

app in every category during the month of its release.

30

Since then, the

game has been released for Google Play, HTML5, and the Tizen OS. By

May 2016, it had been downloaded almost 120 million times.

31

2. Access to funding. New artists have benefited greatly from better

access to local and global Internet-based crowdfunding platforms. A

long-standing major obstacle for the “consumer-creator” model has been

access to the financing needed to make professional products that

consumers are willing to pay for. The Internet is enabling new sources

of funding that support new niche markets, where everyone can pitch

projects to the “crowd” in an eort to receive financing by multiple

(mostly small) donors.

34 Strategy&

In India, for instance, online crowdfunding platforms such as Wishberry

are contributing to the growth of local nascent creators. The rock band

Parvaaz was able to raise $4,000 in less than two months and build a

solid fan base along the way. Following the release of their album in

2014, the band was invited to perform at popular music festivals and

later toured India.

32

And Tim Lea, an independent film director and

writer from Australia, financed his sci-fi feature film 54 Days by raising

$45,000 through Pozible, an Australian crowdfunding site, in just one

month. The critically acclaimed film was made available to the public on

three video-on-demand platforms.

33

3. Increasing support from dedicated platforms. The rise of the MCNs

has added considerably to the ability of new video artists to bring

attention to their work, providing them with assistance in production,

distribution, monetization, and audience development. In fact, seven of

the top 10 YouTube channels in Australia and five in India feature new

artists supported by MCNs. Australian teen Troye Sivan emerged as an

online star thanks to the success of his YouTube channel, produced by

Boom Video, an MCN; it boasted 4 million subscribers in May 2016.

34

Time

magazine listed Sivan as one of the 25 most influential teens of 2014.

A variety of new digital distribution platforms now focus on distributing

the work of independent artists in various fields while providing them

with other kinds of support. India’s OK Listen! allows up-and-coming

Indian artists to make their songs available on its platform, while also

helping the artists create the artwork for their songs and promoting them

across online channels. The site supports more than 200 new artists.

4. Greater bargaining power. By removing the middleman from the

value chain, the digitization of Thailand’s book industry has allowed

authors to receive a larger share of the revenues from the sale of their

books— 70 percent versus 10 percent in the traditional print model—

while readers benefit from lower prices for e-books.

Like the music industry in other countries around the world, South

Korea’s music industry used to be firmly controlled by the country’s

record labels, which created and developed talent, managed the careers

of artists, and saw to all content promotion and distribution. The

Internet has increased the bargaining power of independent artists by

providing them with a platform to showcase their work and reach

audiences directly, in a cost-eective manner. (See “The changing value

chain in the South Korean music industry,” page 36.)

35

New dynamics brought by the Internet

Digital models, driven by the proliferation of the Internet, are fueling a

renewed growth in creative sectors. Increasingly, the power is shifting

to consumers, who decide what they want to make, what they want to

consume, and how and when they want to consume it. This change has

been the primary driver of innovation and investment in creative

sectors. Succeeding in this digital environment requires a dierent

approach and recipe than in the past. Players that have managed to

adopt these new models have benefited from this growth.

Although this report focuses on the impact of the Internet on creative

sectors, the Internet is a powerful tool that has had a significant impact

on society as a whole. As transformative as the Internet is to individuals’

lives, it also creates new economic opportunities. The expansion of

Internet activity has stimulated economic expansion, job growth, and

poverty reduction (especially in developing countries).

The Internet’s impact on the creative sector follows a similar evolution.

The penetration of mobile broadband increased at a compound annual

growth rate (CAGR) of 5 percent and smartphones by a CAGR of 31

percent from 2011 to 2015 across the five countries, and the digital

creative sector grew at a rate of 7.5 percent during this period. In

aggregate, 84 percent of the $15 billion in revenues added to the

creative sector can be attributed to digital. Consequently, the digital

share of the total creative sector in these countries increased from

11 percent to 18 percent in the same period.

Consumers have embraced the digital world. They are spending more

time consuming creative products. The quantity and relevance of

creative products have increased steadily, and the barriers to becoming

a creator have been lowered. Consumers are actively engaged in the

creation of content themselves, with many reaching global audiences.

New creators and companies that have emerged are providing locally

relevant content in new genres, adding to the variety of local content.

In developing nations such as India, the Internet is also driving

social inclusion by enabling consumers in remote areas to access

informational, educational, and entertainment content for the first time.

While the demand for creative content is increasing, it is also

fragmenting. Traditional media players must now compete with purely

digital brands and platforms for the time and attention of the consumer.

In this world, traditional oine media strategies will be very hard to

defend. Agility and speed are as important as size, often favoring new

players. Cannibalization of traditional revenue streams and fear that

their current assets will be devalued have been holding back some of

the established players. New propositions, frequently led by technology,

While the

demand for

creative content

is increasing,

it is also

fragmenting.

36 Strategy&

need to be launched rapidly, tested in the market, and adapted quickly

based on consumer feedback. This approach can be challenging,

especially in large corporate settings. But as long as the consumer

benefits and spends more time with media, the creative sector will find

a way to thrive. Many new digital media possibilities will not replace

old media channels but rather augment them.

We are in the early stages of digitization of the creative sectors. The

evolving digital ecosystem in creative sectors will be much more fluid,

but it will also present abundant opportunities for all players. We expect

the Internet to contribute $15 billion more to the creative sectors of the

five countries in the next five years. Traditional players that are able to

embrace the new models, in the same way that consumers have, stand

to benefit immensely.

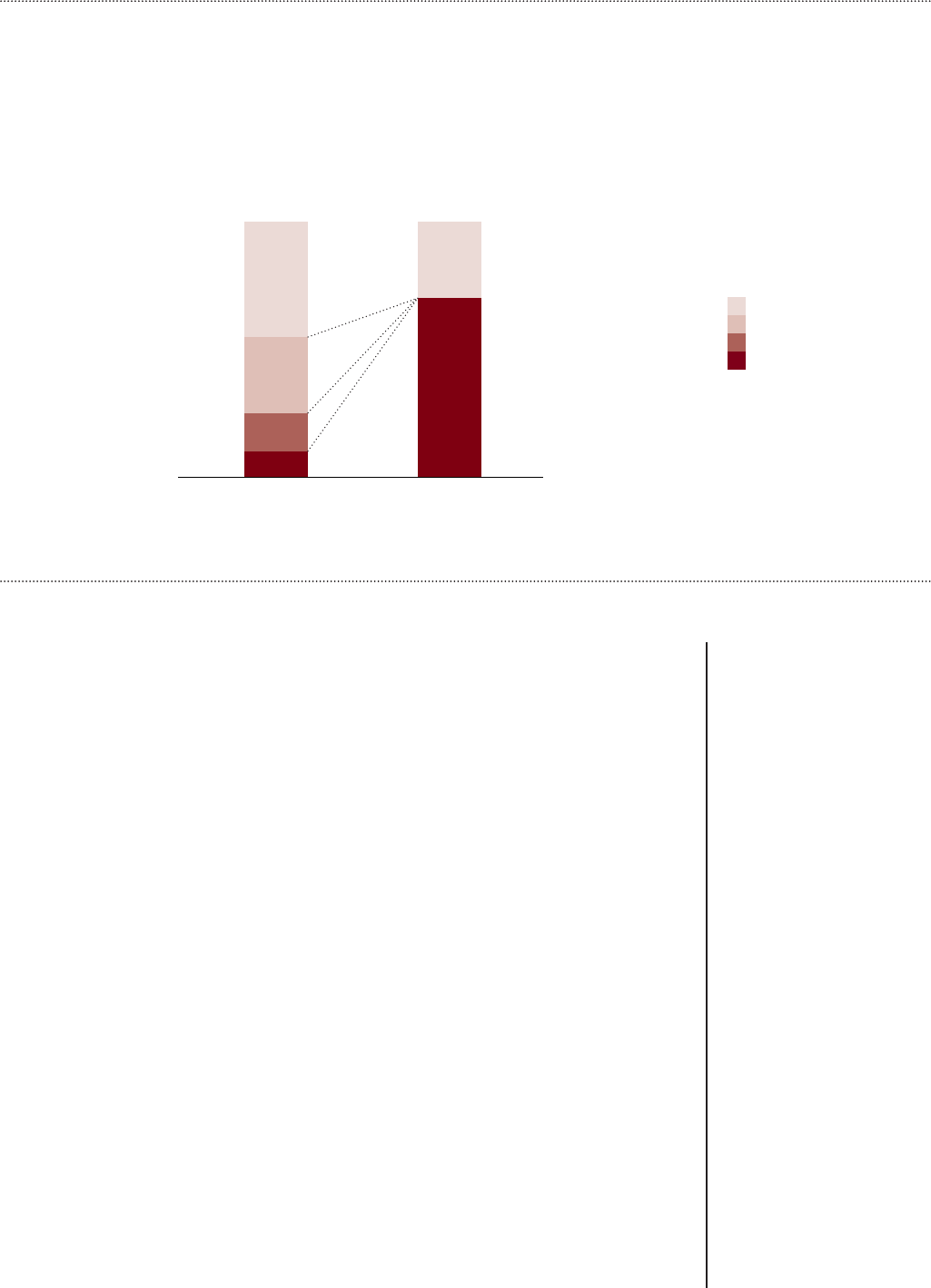

The changing value chain in the South Korean music industry

The Internet has already had a significant

impact on the music industry in South

Korea, which had long been controlled by

just a few major record labels that tightly

managed every aspect of the business.

Exhibit A, next page, illustrates how the

industry used to be organized, and how

that’s changing under the influence of the

Internet. Traditionally, labels controlled

content creation and talent discovery,

auditioning, hiring, grooming, and

training the artists, and then producing,

marketing, and distributing the music.

Without a contract with a record label,

artists found it very dicult to get

exposure for their music. Distribution and

sale of CDs was the largest revenue stream

for both the large and small record labels.

The barriers to entry for new artists

have dropped, thanks to lower costs

of production, distribution, and

promotional methods such as viral

marketing. And because the Internet

oers transparency into an artist’s

popularity, talented newcomers now

have easier access to funding from record

labels. The user feedback available on

various platforms such as social media

allows artists to adjust their styles and

songs based on that information.

For record labels, costs are lower,

audience reach has risen, and they can

find new artists more easily through

techniques such as online video auditions

and metrics such as hits and downloads.

Meanwhile, revenues no longer have to

be split with CD manufacturers.

Smaller labels in South Korea, however,

face a more dicult environment. The

commissions they must pay to the top

music distribution platforms are actually

higher than the cost of producing CDs

and DVDs, and top artists, who can

demand a higher percentage of sales,

often prefer signing contracts with the

large record labels.

37Strategy&

Traditional process

Online process

Content

creation

Talent

discovery

Production Marketing Distribution/monetization

Professional

artists groomed

by record labels

Traditional record labels

Major South Korean record labels audition, hire, groom,

and train talent, then produce music and market and

distribute it to consumers, monetizing it through

brick-and-mortar outlets as well as concerts

CD/DVD sales in

physical stores

Concerts

Merchandise

Traditional record labels

(e.g., S.M. Entertainment, YG Entertainment)

Digital

labels

Self-

production

CD/DVD sales in physical

and online stores

Concerts

Merchandise

Artist websites and/or

dedicated apps

Online music

distribution platforms

(e.g., Olleh Music, MelOn, Mnet)

Digital marketing

platform (e.g.,

PMC Musical)

Artist website

(e.g., A-Ble)

Social media

(e.g., YouTube)

Online music

distribution

platforms

Independent

artists

Traditional

model

Internet

model

Professional

artists groomed

by record labels

Digital marketing

platform (e.g.,

PMC Musical)

Artist website

(e.g., A-Ble)

Social media

(e.g., YouTube)

Online music

distribution

platforms

Source: Interviews with

large and medium-sized

record labels; Strategy&

analysis

Exhibit A

A changing value chain: South Korea’s music value chain before and after the advent of the Internet

38 Strategy&

Chapter 1

Japan: Growth in a contracting

economy

Although Japan’s overall economy continues to struggle— it contracted

by 9 percent yearly between 2011 and 2015— its media sector actually

grew annually by 1 percent over the same period, to $73 billion in total

revenue, and is expected to continue to grow through 2020. Much of that

increase has and will continue to come from the rapid growth of digital

content. In 2011 digital content made up 11 percent of the overall sector’s

total revenues; by 2015 that proportion had reached 18 percent, and by

2020 it is expected to rise to 25 percent (see Exhibit 13, next page).

Trends shaping Japan’s creative market

The digital share of Japan’s total creative sector revenue is quite high,

and compares favorably to that of India (6 percent), Thailand (9

percent), and Australia (17 percent). Only South Korea’s digital sector is

significantly more developed, at 35 percent. The strength of Japan’s

digital media sector is largely attributable to its high level of fixed

broadband penetration (76 percent), mobile broadband penetration

(119 percent), and smartphone penetration (77 percent) in 2015.

Driven largely by broadcast TV, Japan’s video market is still the largest

contributor to its overall creative sector. In fact, Japan is the largest TV

advertising market in the Asia-Pacific region, and it is expected to

remain so until 2020 and beyond. At 2 percent annual growth between

2015 and 2020, Japan’s TV market is expected to reach $24 billion in

2020. The home entertainment portion of the video sector is expected

to grow revenues at a slow but steady 1 percent annual rate between

2015 and 2020, reaching $6 billion in 2020. Local box oce content is

key for audiences in Japan, in which nine of the top 20 movies of 2015

were Japanese-made.

Digital compensates for traditional sector revenue decline. Japan’s

digital creative sector is projected to grow at 11 percent during this

decade (2011–20) to reach $19 billion by 2020. The growth in digital

content has more than compensated for the decline in revenues on

traditional platforms and is expected to continue to do so.

39Strategy&

Note: Results of

calculations may not be

exact due to rounding.

Source: PwC’s Global

Entertainment and Media

Outlook; Strategy& analysis

Exhibit 13

Strong growth in Japan’s creative content sector

Japan’s media market size by sector

(per capita gaming expenditure in US$ billions

)

CAGR

(2011–20F)

+1%

+1%

2011

$70

34%

33%

14%

10%

9%

2020

(forecast)

$78

39%

26%

13%

17%

-3%

2015

$73

35%

29%

13%

14%

8%

-1%

+3%

+0%

+7%

-3%

2011

$8

3%

8%

11%

65%

13%

2020

(forecast)

$19

12%

15%

13%

57%

4%

2015

$13

11%

13%

10%

62%

5%

CAGR

(2011–20F)

+16%

+32%

+13%

+9%

-3%

Japan’s digital media market size by sector

(in US$ billions)

+15%

+8%

Books

Print

Video

Music

Games

40 Strategy&

Japan’s digital media sector is dominated by online gaming, which will

likely continue to take in more than half of all digital revenues through

2020, owing to its consistent growth rate of 9 percent. In fact, Japan’s

online gaming industry is among the largest in the world, and it’s driven